By Jarrod Shanahan

Brooklyn Rail

June 2020

AngryWorkers want you to build an international revolutionary

organization guided by the axiom “the emancipation of the working

classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves,” and they

have a plan. Six years ago the communist grouplet relocated from London

to a western industrial suburb called Greenford, where they found a

dizzying array of industrial and logistical facilities central to

keeping Greater London running. Greenford, they discovered, “typified

one of capitalism’s main contradictions: that workers have enormous

potential power as a group, especially if they could affect food supply

into London, at the same time they are individually weak.” AngryWorkers

set up shop and organized tirelessly inside and outside the union

structure in a number of industrial workplaces, in community campaigns

against austerity and their own solidarity network, and through the WorkersWildWest newspaper

which they distribute at factory gates at the crack of dawn. None of

these practices are new, and some may seem better left in the 20th

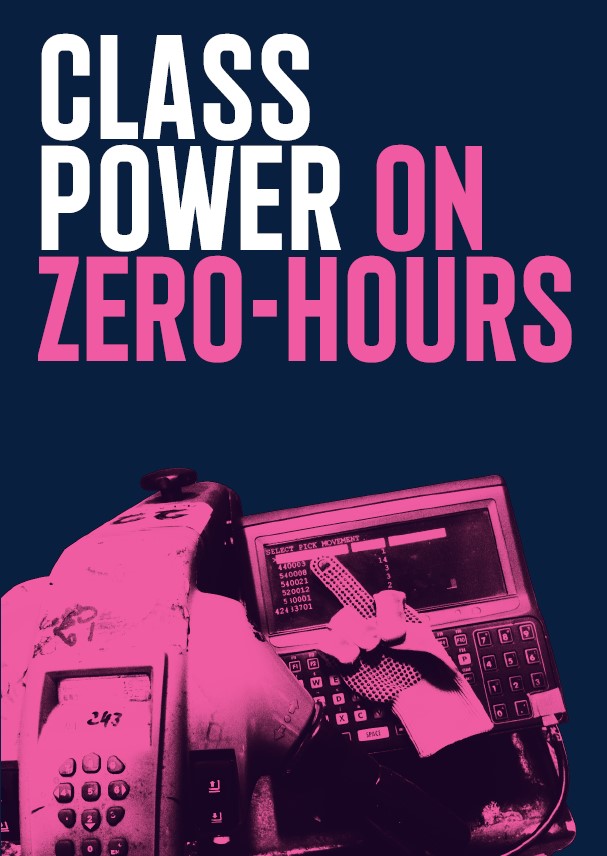

century. But AngryWorkers’ new book Class Power on Zero-Hours (London:

AngryWorkers, 2020), a sustained reflection on the past six years of

this organizing, reveals their praxis to be even more timely than

authors could have known.

Class Power recounts the group’s organizing experiences and the

lessons they have drawn from them, while underscoring the necessity for

coordinated working-class rebellions throughout global logistical

networks, and the imperative for the UK left to change courses following

the defeat of its social democratic ambitions in the figure of Jeremy

Corbyn. By sheer coincidence the book hits shelves as the COVID-19

crisis has dramatically heightened social dependency on services like

Amazon and Instacart, and thrust logistics workers’ struggles into the

open as increased exploitation and dangerous working conditions add more

fuel to the fire across the supply chain. Simultaneously a new

generation of self-proclaimed socialists in the United States are

reeling from the electoral defeat of Bernie Sanders, just as Corbynites

were as Class Power was headed to press, and vow in great

numbers to exit the US Democratic Party in search of more radical and

unmediated forms of political participation. May this wonderful book

fall into their hands, and those of all searching for direction in a

moment of great transition, when few things are certain beyond the

surety of heated struggles to come.

Getting Rooted

AngryWorkers delight in having found a base of operations of which many

London leftists have never heard, and consistently contrast their

experiences in Greenford with vogue theories of “post-industrial”

societies and “immaterial labor” which thrive among urban

intelligentsia. A far cry from post-industrial, Greenford is

home to a highly-concentrated international proletariat largely hailing

from Africa, South Asia, and Eastern Europe and thrown into fraught

relations of cooperative labor at similarly heterogeneous points of

production. AngryWorkers argue that places like Greenford represent the

return of large concentrations of workers in space, following capital’s

decades-long restructuring of productive relations away from large

centralized factories that could serve as proletarian strongholds.

Accordingly, they argue that Greenford and places like it present

Achilles’s heels of capital in its present composition, begging

concerted communist organizing. One nearby office park, which

AngryWorkers dubs the “crown jewel of a workers’ vanguard,” boasts

40,000 workers laboring in 1,500 businesses ranging food production,

custom printing, tech, transportation, laundry, waste processing,

hospitality, and studio film production, alongside a hospital,

international student housing, a massive supermarket, and all kinds of

cafes and other working-class haunts. “We have to contrast the strategic

joy of engaging with this potential jewel of a working class movement,”

they write, “with the stale and often airy Labour party politics and

internal power-fights that many London lefties prefer to get involved

with. We ask ourselves: what the fuck?!”

The group suggests that anyone can simply walk around a place like

Greenford with their eyes and ears open and learn a lot about the world

they live in. But the treasure trove of thick descriptions and practical

wisdom which fill Class Power’s nearly 400 pages is largely

derived from years of full immersion in Greenford life, and purchased at

great exertion of time and energy of a small group of dedicated

militants. To get rooted in Greenford, AngryWorkers took up in crowded

proletarian neighborhoods, labored for years on end in low-wage

warehouse, factory, and transportation work, and merged their social

lives with the dense local networks that crisscross thousands of shops

drawing on temp workers, zero-hour (no work guaranteed) contracts, and

other ingredients for high turnover. “You can do a lot more than you

think,” they remark, “when your ‘political life’ and ‘normal life’ isn’t

so divided.”

Getting to Work

“As an organization we take on a responsibility,” they write. “The

responsibility to help turn the global cooperation of workers, which is

mediated through corporations and the markets, into their own tool of

international struggle.” While the group scorns programmatism, their

model is tripartite, combining intensive workplace organizing,

solidarity networks and other community engagement, and regular

distribution of print propaganda whichcollects grievances and

other seeds of potential workplace campaigns, reports on strikes in

similar workplaces or nodes on the same supply chain, and conditions of

daily life outside the factory. This final item has provided much of the

raw material for Class Power, and demonstrates laudable

efforts to move beyond the same old jargon and sloganeering and write

for an audience far removed from the Facebook International. Above all,

the honesty and self-critical stance from which they evaluate their

organizing provides a wealth of practical reflection for organizers in a

variety of settings.

For starters, AngryWorkers intend the solidarity network model to ground

them in Greenford’s proletarian life and begin to tap the networks that

traverse workplaces and neighborhoods. Class Power recounts a

number of these campaigns, introducing the reader to Senegalese kitchen

workers, Bulgarian apple pickers, Moroccan factory works, Somali bus

depot cleaners, Punjabi truck drivers and construction workers,

Sundanese hotel workers, and Polish tenants, united by their common

status as highly exploited laborers and tenants, often victimized by

more affluent and better-rooted members of their own “communities.” As a

kind of organizing first principle, they opt to avoid a formal

organizational name or “brand” identity, concerned that a clear

organizational identity could become a fetish object, obscuring from its

participants the material reality that their collective activity

constitutes the group’s power.

The group narrates its initial trouble getting over the hump of making

contacts. Film screenings and open hours at community centers fail to

attract workers, they change tacks and set up at working-class cafes,

including a McDonald’s. This pivot attracts far more interested workers,

who bring with them rich social networks traversing the region, replete

with experiences of exploitation upon which campaigns could be built.

Predictably enough the solidarity network runs into problems typical of

the model, namely their inability to transcend the “service” model which

nonprofits and social workers have conditioned working people to expect

in place of direct-action and empowerment. They also have trouble

getting workers to stick around after their campaign has been won.

Nonetheless, they rack up back wages to the tune of £25,000, and along

with local efforts against library closures and the demolition of a

working-class community center, demonstrate in practice the remarkable

heterogeneity of Greenford’s proletariat and the invisible lines of

interconnectivity that run throughout neighborhoods and workplaces. In

their critical reflections, they wonder if a more formal structure would

have proven more effective and sustained better over time. It is an

open question with the solidarity network and all of the AngryWorkers

projects, and it is a question that can only be addressed in practice.

The centerpiece of their strategy is workplace organizing, which lands

AngryWorkers comrades in refrigerated warehouses, prepared food assembly

lines, labyrinthine distribution centers, auto transportation across

the so-called “last mile” between warehouse and the consumer’s home, and

even a shop manufacturing 3D printers, which they discover to be a full

180 degrees away from the feel-good techno-utopianism of “open source”

ideology. Their guiding praxis seeks to identify and encourage worker

militancy, rather than recruit people to a group or a particular

political standpoint. Once a comrade has taken root in a shop, they

begin to identify grievances and potential seeds of struggle. While this

comrade plays it tight to the vest, slowly building the trust of

workers and not making their politics known, comrades on the outside

distribute literature outside the shop, and stories from these various

workplaces appear in WorkersWildWest.

All the while, the comrades on the inside toil under arduous, bleak (a recurring adjective in Class Power),

and near-dystopian conditions. They take months and even years to build

the basis for a single campaign, all the while engaged in punishing

daily regiments. In the refrigerated “chill” warehouse, for instance,

the comrade stuck in there all day must sort boxes and trays of food at a

fast pace, with their forearm adorned with a computer console that

gives orders and connects to a finger-mounted scanner monitoring

productivity! If they sink below the required pace, they receive a text

message warning, followed by loss of work. All this, on temp wages. When

they are finally fired for organizing a slowdown, after the better part

of a year in these conditions, they don’t seem too sad to go.

Tellingly, the biggest obstacle facing their organizing efforts was the

high turnover, and the propensity of the ablest would-be militants to

simply quit in search of better conditions and pay instead of working

long-term to build worker power in the shop. And who can blame them?

In this work AngryWorkers draws inspiration from the present syndicalism

renaissance, in particular the organizing of Italy’s SI Cobas,1

militant unionists in the logistics sector whose actions AngryWorkers

publicize in their factory newspaper as potential inspiration for

English workers. They are appreciative but more critical of the en vogue approach championed by labor expert Jane McAlevey, author of No Shortcuts (Oxford

University Press, 2016), who they argue correctly points for a need to

break with top-down “service unionism,” but does not sufficiently break

from the binary—and often hierarchy—of “organizer” and “worker” inherent

to professional labor organizing. By contrast, the AngryWorkers call

quite rightly for the abolition of waged union jobs and professional

organizing altogether. At the same time, they draw influence from “class

unions” like the IWW, who they partner with in a number of campaigns,

but question the use of conflating unions with broader political organs

of a working-class offensive.

Above all, their calculus of workplace strategy is guided by an aversion

to allowing unions, or any organization, to become a fetish object

standing above the power that working people wield when they take action

in concert. These motives are understandable to any critically-minded

person who has engaged with a contemporary labor union and suffered its

vapid sloganeering, quasi-military hierarchy, and mystification of “the

union” as greater than the struggles of its members—all while leadership

acts as the left wing of management, enriching itself and perhaps a

tier of the highest-waged workers at the expense of everybody else. Yet

it is perhaps the greatest strength of the AngryWorkers’ praxis that

they do not merely abstain from union participation on principle, but

experiment with the union itself as a potential site of struggle.

As astute observers of contemporary capitalism, AngryWorkers believe

unions “essentially exist to manage the relationship between labor and

capital rather than overcome it,” as one member working at a food

production facility writes. “But rather than rely on left-communist

dogma,” they continue, “we wanted practical experience within the big

unions to see how things actually operated.” Thus begins a multi-year

experiment working as a rep in a rotten company union which scarcely

masks its pact with management against the workers. Taken in sum the

worker-cum-rep’s experiences surely do not contradict “left-communist

dogma” about the structural role of unions in capitalist society.

Simultaneously, however, they provide a nuanced account of how union

offices can be used as a strategic point of leverage for building

extra-union worker power.

For instance, under the cover afforded by the union rep position, this

worker was able to openly collect and socialize grievances, distribute

literature, network with more militant workers, and help organize a

number of protests demanding pay increases—all to the chagrin of the

union and its partners in management, who aren’t immediately able to

clamp down. Similar conclusions are drawn from another comrade’s account

of working as a rep in “last mile” delivery, who concedes the decision

to give union office a whirl arose in part when “our efforts to create

independent structures didn’t go too far.” Far be it from me to ever

endorse the star-crossed endeavor of “union reform,” but these accounts,

far too detailed to do any justice here, provide valuable reflections

for workers in a unionized shop wondering where they can find the best

possible leverage. Like all questions addressed by the AngryWorkers

praxis, the answer is not an easy one.

Getting Acquainted

In the course of their struggles AngryWorkers have produced an immense

body of writing for the purposes of agitation, debate, and to deepen

their own understanding of the complex social world in which they are

taking action. The best of it recalls Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England

or the propaganda tracts by the enigmatic writer and illustrator known

only as Prole. In contrast to the odd journalist or photographer who

slums it for a short stint to document the lives of poor downtrodden

workers, AngryWorkers are attentive not just to the obvious deprivation

but to the potential power workers wield in daily cooperation and

resistance. And in contrast to the sectarian, they are not simply

looking for recruits, or to “colonize the factory” as many New Left

groups attempted in the 1970s. They seek instead to identify working

class initiative where it already exists and help generalize it across

shops, supply chains, and entire regions. Thus when they engage with the

contradictions of working-class life which emerge from divisions of

productive and reproductive labor riven by race, gender, ethnicity,

citizenship, language, and other factors, it is with a view to how these

real differences can be overcome to constitute the class as a fighting

force.

In two particularly profound lines of inquiry, originally composed for their propaganda and excerpted in Class Power,

AngryWorkers examine “the crisis of the working-class family” and the

particularity of women’s experiences in the gendered division of factory

labor and bearing the brunt of austerity at home. Lengthy testimonials

from three women speak to a diversity of backgrounds—the young Hungarian

woman who seeks above all freedom from her hometown, the Irish mother

who struggles to balance the impossible calculus of work and care for

her autistic son, the Punjabi mother of two who lives precariously from

visa to visa and has not seen one of her daughters in six years—grounded

at once in a common condition of hyper-exploited labor. As bourgeois

feminism enjoys its day in the sun, these working women’s voices

demonstrate at once the complexity and necessity of approaching gender

analysis from a perspective grounded in the work and home lives of

working-class women. This method, AngryWorkers clearly state, is

distinct from considering “class” as one particular form of

“intersecting” modalities of oppression. Class, instead, is the basis of

exploitation, and the very real and often devastating particularities

of exploitation along lines of race, gender, citizenship, and so forth

are, to pluralize a famous dictum from Stuart Hall, “modalities in which

class is lived.”

These stories and other investigations AngryWorkers undertake paint a

complex and visceral portrait of gender and working-class family life as

immiserated by crushing austerity while rendered evermore necessary by a

deepening harshness of life outside. An inquiry entitled “The Crisis of

the Working-Class Family” builds on their analyses of gender and

workers’ living arrangements to explore the family as a stopgap for the

near-impossibility of survival on working-class salaries. The

working-class family, they argue, is largely a necessity arising from

the impossibility of being alone, and is accordingly packed into

whatever tight living quarters workers can muster, which is often

collective living with extended family or workmates, where the specter

of the exploitative sub-landlord is never far. Simultaneously they argue

that the heterosexual couple, defined by the desperate need to keep

“romantic love” afloat, has become the sole outlet of emotional

expression in search of rich expression, especially for men. The

combination of these elements, they argue, renders working-class

families combustible compounds defined by frustration, desperation, and

strife, which episodically erupt into violence, most often men against

women. While it is difficult to read these passages without feeling

claustrophobic, it is simultaneously powerful to read the concepts of

social reproduction, gender, and the family analyzed through the lives

of real working-class people and in relation to their raison d’etre,

surplus value production.

Another welcome intervention comes around the question of automation and

its relationship to low-waged work. “The whole spiel about ‘full

automation’ is bollocks,” they write in a discussion of the

labor-intensive “chill” warehouse. “Here we are, using thousand-year-old

technology…wheels!…to help us do the bulk of the work, while being

controlled by 21st century high-tech. We are cheap, so why replace us

with robots, which would have difficulty fitting the big banana boxes

into the small cages anyway?” This example is a common theme throughout

the book, as high-tech enables companies to juxtapose automation

technology with disposable low-wage workers, whose resiliency and low

cost or commitment make them a cheaper option than full automation.

Importantly, the onus of discipline still rests on the human element. In

the same passage, they continue:

But low-tech also means that the command of work is not transmitted through a big technical apparatus, which we might hate but at the same time admire and accept. Instead, the command of capital is primarily transmitted through the strained vocal cords of the dumpy managers, who stand and scream at the end of each line: ‘Andranik, stop talking to Preeti, get a move on!’

Elsewhere, they include a photograph of three workers struggling against

a giant crate, with the caption: “Who needs a forklift when you have

three men to move a ton of cabbage?”

As a textual whole, Class Power calls to mind the eccentric genius which strikes the first-time reader of Capital, and while lacking the lengthy mathematical interludes, Class Power

compensates with extensive histories of supermarkets, food

distribution, and West London itself, interspersed with hundreds of

pages of workplace writing at once baroque and immanently practical. The

characters who emerge are complex yet immediately recognizable—the

pissed off temps whose excessive drinking sends an organizing meeting

off the rails, immigrant workers who vote for Brexit to flip the middle

finger to the status quo, the self-styled “rebels” who chicken out when

the time comes to take risks, and perhaps above all, the authors

themselves. The book’s authorial voice episodically changes from plural

to singular as individual yet unnamed and ill-defined workers step forth

to recount their particular experiences before once more dissolving

back into a faceless we. All the while the text preserves a loose sense

of narrative style and a breezy, bathetic, shit-talking sensibility

which makes the collective author the kind of person the reader would

want to have a beer with and maybe listen to a multi-century history of

capitalist agriculture in the process.

Getting Together

By way of a conclusion, AngryWorkers provides something rare among

groups who do not simply reproduce the received texts of the 20th

century: a clear account of how their daily activity connects with the

global communist revolution. “There is no lack of revolutionary anger,”

they write. “What we haven’t seen is a section of the working class that

focuses on the real centres of power—the grain baskets, manufacturing

centres, ports, power plants—with the aim and a plan to take them over.

It might take a few more waves of struggle for such an organized force

to emerge,” they write, but insist nonetheless on the guiding question:

“So what are the bare necessities during a revolutionary transition?”

What follows is a detailed account of how strategic working-class

takeovers throughout the social division of labor could simultaneously

build revolutionary momentum and ward off counterrevolution or

stagnation, the latter most likely to arise from hunger caused by

interruptions of food from the countryside and abroad. “The

communisation-fun,” they tease, “might last three days max before you

start getting hungry.” Here the true prize of their years in Greenford

reveals itself: a practical and strategic understanding of the social

division of labor necessary to reproduce the infrastructure of an area

as complex as Greater London, an understanding which can serve as the

basis for theorizing a revolutionary offensive.

This is not to say that their plan—or anybody’s plan—could be followed

to the letter in a moment of revolutionary transformation. Nor do they

intend this text to be treated in the manner of those who still thump

the Transitional Program onto the table as it approaches its

centennial. Instead, rooted in their own practical-critical

investigations into current compositions of class and capital, they have

created an arc which few of us dare to consider in conversation, much

less commit to publication, between the challenges facing small bands of

organizers attempting to get a toe-hold in strategic centers of

production and circulation, and the bare requirements of going all the

way. It is a perspective far removed from fighting injustice, sticking

up for the powerless, speaking truth to power, purifying oneself from

the evils of capitalism, and inching toward a vanishing horizon of

socialism through piecemeal electoral gains. Instead, it poses a simple

question: how do we build the power it will take to win?

Class Power on Zero-Hours is not without its shortcomings, but

like all great works, its weaknesses are simply the underside of its

strengths. For instance, in their practical analysis of the local

working class, AngryWorkers return time and again to the abstraction of

“the community,” meaning cross-class networks bounded by common

language, nationality, and faith. They correctly argue that these

communities are led by petty bourgeois “leaders” whose

interests—expressed in exploitative employment, housing rental,

citizenship schemes, for-profit language classes, and so forth—are

opposed to the interests of their “community’s” working people. The

AngryWorkers theorize this relation as a basis not only for exploitation

in the present but for authoritarianism in the future, an idea borne

out in their workplace organizing and solidarity networks, where they

encounter coercive “community” relations that prevent workers from

standing up to their bosses and landlords. They have therefore

identified a central contradiction facing the contemporary revolutionary

left, and one which runs many organizers’ revolutionary praxis aground,

as they embrace the abstraction of “community” and thereby lend their

support to cross-class alliances which lead nowhere.

Unfortunately, in formulating this practical analysis, AngryWorkers do

not take seriously enough the powerful objective forces which give these

community leaders their strength. When workers complain of racism in

the factory, the group is quick to offer alternative explanations more

directly tied to the shop’s division of labor. While AngryWorkers do not

dispute the reality of racism and xenophobia, and document extensively

the sick mischief such chauvinism causes among the working-class, they

appear to not consider the color line itself a worthy basis of struggle.

This is doubly frustrating as their own theory, expressed by their

masterful critique of social democracy, decries placing the abstraction

of formal “unity” ahead of unity produced by taking contradictions like

the color line head-on. The group’s aversion to advancing race or

nationality as the basis of struggle is understandable given how

decoupled the two have become in middle-class left analysis. But the

fact that “anti-racism” has become a lucrative industry for building

university and non-profit careers that don’t challenge capital in the

slightest, makes it all the more necessary to carve out a strategic,

working-class anti-racism that takes the color line head-on in pursuit

of the strategic lines AngryWorkers draw so deftly.

A more obvious criticism, which surely dawns on the authors, is that

their individual campaigns have largely come to naught, especially

weighed against the group’s cyclopean labors. Over the years their small

core has attracted a rotating lineup of comrades from across Europe and

even South Asia, but the arduous work and scant unambiguous victories

seem to have made retention in their Greenford cadre about as difficult

as at the local factories themselves. One chapter, recounting an arduous

multi-year organizing effort, concludes: “Things didn’t work out this

time, but that’s the class struggle folks! Better luck next time!” As

this sentiment recurs in various forms throughout their innumerable

efforts, the reader gets the sense that the core comrades are possessed

of a certain disposition which makes them as suitable for this work as

they are rare among the contemporary revolutionary left. Unfortunately,

“better luck next time!” might be enough for a core of stone militants,

but the breakneck pace and dizzying array of campaigns which this small

group took on in a short time seems like a recipe for burnout,

especially absent the galvanizing effect of tangible wins.

Similarly, it is both a strength and a weakness of AngryWorkers that

they attribute their failures thus far to a lack of capacity or

unfortunate turns of events. Ultimately their scrupulously detailed

critical reflections are less concerned with why things didn’t work and

more occupied with how they could have gone differently. This is a sign

at once of great optimism of the will, and also perhaps of a dose of

stubbornness. To these critiques, I’m sure, the authors will reply: all

of this is true, and that’s why you should join us to effect the shift

from quantity to quality!

Accordingly, Class Power concludes with an invitation to

comrades around the world—any town where there are at least two—to begin

practical-critical investigations of nearby workplaces and

infrastructure strategic to working-class insurrection, take up

occupations there whenever possible, build solidarity networks, and to

generalize this practical-critical work with the similar efforts of

groups all over the world. Not all readers (present company included!)

will be willing to cast aside whatever they’re doing and take up

employment at physically punishing low-waged labor in these strategic

sites. But some will, and the AngryWorkers are clear that important work

remains outside the workplace, to agitate, organize in solidarity

networks, support the comrades inside, and help build more generalized

networks of shared practical knowledge. To this effect, the group has

been organizing video conferences, necessitated in part by COVID-19

quarantine, and has continued a dizzying output on their website.2

They are offering literature and flyer templates and practical advice

to anyone seeking to pick up the torch in their own town. If you are on

the fence, don’t take my word for it—reach out to them!

Class Power on Zero-Hours is a difficult book to review, given

its immense wealth of practical information and its scrupulous

recounting of the high price its authors paid to earn it. Moreover, Class Power

is simply a multiplicity of books—not just in its immense length, but

in the rich variety of its content. What might be a throwaway paragraph

to one reader might grab someone with experience in commercial trucking

as the most poetic and damning description of their lives they have ever

read. Same for exploited tenants, women harassed by their bosses,

perennially stymied workplace militants, migrant workers anxious about

the ascendant right, and so forth. It will be a different book to

practically every reader, and will engender vibrant discussion that

grounds strategic horizons in the lived experiences of working-class

people. Accordingly, this reviewer strongly suggests the formation of

study groups wherever possible, among workers already struggling around

the COVID-19 crisis (wherever their time allows), organizers who find

their terrain of struggle turned upside down, and everyone wondering how

best to join the fight. “It can sometimes be frustrating and depressing

when you’re on the front lines of the class war,” the AngryWorkers

conclude, “but on the whole, it’s exhilarating and purposeful and gives

us the means to live how we want.”

-

For English writing by and about SI Cobas, visit https://libcom.org/tags/si-cobas.

- Angry Workers of the World: Precarious and Unruly, https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com.