By Ted Glick

Future Hope Column

August 23rd, 2020

Over the last 7-8 years my wife and I have spent the summer months raising monarch butterflies. We learned to do this because the number of monarchs in the United States has dropped precipitously over the last 25 years primarily because of habitat destruction and global heating. The number of monarchs making it to their main winter gathering site in Michoacan, Mexico has gone way down over that time. The years 2012-2014 saw an overwintering monarch population about 90% below what it was 20 years earlier. This was when we and many other people around the country began growing milkweed.

Milkweed is where female monarchs lay their eggs, on the underside of the leaves. Several days later a tiny caterpillar emerges and begins eating milkweed leaves, which it does until, about 10-12 days later, it becomes a beautiful, two-inch long, yellow, white and black caterpillar, at which point it attaches itself to the underside of a leaf and turns into a chrysalis, or cocoon. About 12 days later it emerges as a beautiful butterfly.

Why have my wife and I and tens of thousands of others intervened in this process? For us, it’s because of their near-extinction, first, and then our learning from a good friend, Trina Paulus, that only 10% of the eggs ever make it to the butterfly stage in nature because of insects or birds eating the eggs or the caterpillars. When raised the right way indoors or in an outside shed, on the other hand, the success rate is about 90%.

After several years of finding, raising and releasing 20-30 monarchs each year, there was a dramatic change in 2018. That year the numbers went up to about 110. Last year they went up to 160. This year, despite a very worrying three-week, late arrival of monarchs in New Jersey (and elsewhere) compared to last year, we may end up with numbers similar to last year, or even more. As of now, we have raised and released 40 butterflies, and we have about 95 chrysalises, caterpillars and eggs.

If this work was begun out of a concern for the monarchs as a species, it has expanded to become something else..

My grandfather on my father’s side used to talk often about a small acorn turning into a mighty oak as an example of the miracle of creation. Jesus in the book of Luke spoke about the tiny mustard seed: “What is the Kingdom of God like? To what shall I compare it? It is like a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and put in his own garden. It grew, and became a large tree, and the birds of the sky lodged in its branches.”

Observing the process of a tiny egg, no bigger than the head of a pin, transforming and changing over the course of one month into a beautiful yet fragile butterfly that then can fly thousands of miles to its species-home in Mexico—this is something special. For hundreds if not thousands of years this has been happening annually. It’s enough to make even some atheists shake their heads and wonder how this could be.

This year I’ve come to realize there’s another reason why I do this.

All of us need to find ways to cope emotionally with the miserable state of human society in much of the world. How do we going, believe that things really can change, that oppression, injustice and violence can someday be replaced by justice, love and nonviolence? For me, spending several months each year connected to nature in such an elemental way is part of how I keep the faith.

When I’m outside working my way through the 100 or so milkweed plants that we have in our garden looking for eggs or caterpillars, I’m experiencing another world, the world of tiny insects living among those five foot high stalks. In addition to the infrequent egg or caterpillar, I see small white triangular bugs, and ladybugs, and other orange and black bugs, and ants, and aphids, and what look like small, green praying mantises, and more. I observe the leaves change from dark green and lush to yellow, green and drying out and then to wrinkled and brown as pods containing scores of brown seeds with white feathery “wings” emerge and wait their fall time to open as the days and nights get colder.

I become more in touch with the cycles of the natural world because of my appreciation of the monarch’s beauty and a desire to help them survive what pesticide-based industrial agriculture and fossil fuel-driven global disruption have wrought on them and so many other living creatures, including human beings.

My commitment to revolutionary change, in the absolute best sense of the word, is deepened and strengthened.

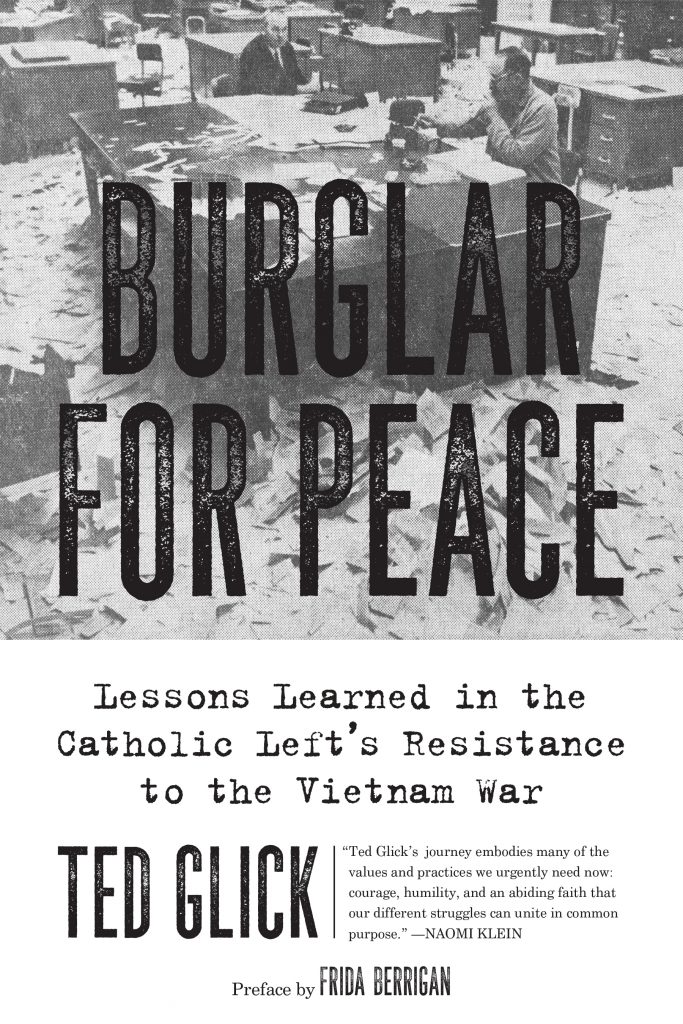

Ted Glick is the author of the just published Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.

Ted Glick is the author of the forthcoming Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in Catholic Left Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.