By Jeremy Brecher

Labor Network for Sustainability

May 18th, 2020

This is the fourth in a series of commentaries on Workers vs. Coronavirus. The first, “Strike for Your Life,” describes how in recent weeks workers in diverse industries and regions have initiated strikes to demand better protection against COVID-19 and how such action might spread. (They did: There have now been more than 100 “COVID-19” strikes.) The second, “I Talk to Workers Every Day – They’re Afraid They’re Going to Die,” tells how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting workers on the job based on direct reports from leaders of seven unions. This commentary, “Unions Protecting ALL Essential Workers,” tells how unions are demanding, bargaining for, and forcing workplace health protections – and how their demands have been incorporated into an “Essential Workers Bill of Rights.”

Every day, 60 million Americans are still going to work. They’re risking their lives to keep our economy going, but don’t have the pay or protections they deserve. That’s why Rep. Ro Khanna and Sen. Elizabeth Warren wrote the Essential Workers Bill of Rights. “Because they should have safe working conditions, health care, hazard pay, and paid sick, family and medical leave,” Khanna says. Watch the video on Facebook to learn more.

Since the beginning of coronavirus lockdowns, the words “essential workers” are suddenly on everyone’s lips. Hospital orderlies, bathroom cleaners, bus drivers – until recently ignored, denigrated, and underpaid – are suddenly treated as heroes. Locked-down Americans stand in front of their houses at 7:00 pm to applaud them. Politicians give speeches celebrating them. These workers were always essential to the running of our society, but now they are being recognized as such. Recognized — but abused more than ever.

Workers who are allowed or required to go on working through the pandemic are being exposed to the coronavirus – and to its economic consequences – with inadequate support from either their employers or their government. In response, workers and their unions have been taking action themselves to provide – and demand – protection.

In addition to action on the job and in government, unions have led the development of an “Essential Workers Bill of Rights” that would provide health, economic, and other protections for these heroic but vulnerable workers. Senator Elizabeth Warren and others have proposed legislation to establish the EWBOR. Now unions are leading a campaign to incorporate the EWBOR in the next stimulus package.

The public has heard little about what unions are doing to protect their members and other working people. In late March the Labor Network for Sustainability convened a videoconference in which the leaders of seven unions provided a snapshot of what they and their members were doing in response to the coronavirus threat.[1] They described first and foremost how unions are pressuring and bargaining with employers and governments to provide equipment and practices to protect workers’ lives and health. But they also described how they have been fighting to protect workers jobs and livelihoods. And how they have been organizing and mobilizing to increase workers’ voice in the decisions that are so directly affecting their lives.

Protecting workers’ health

Healthcare workers have been among the most immediately threatened by coronavirus infection. Maria Castaneda, Secretary-Treasurer of 1199 Service Employees International Union, United Healthcare Workers East which represents a wide range of healthcare workers, said that, “despite the fear,” her members “work every day to take care of patients.” The first thing the union did in the workplace was to “continuously demand with our employers the personal protective equipment.” Meanwhile, it continued to “enforce our health and safety standards in all our hospitals, nursing homes, and home care.”

Another key issue was “salary continuation” when “a member needs to be quarantined for exposure.” Childcare was also important, because “when the schools closed, that created a hardship on healthcare workers who have young children and school age children.” The union promoted childcare programs that support healthcare workers so they can continue working. In Massachusetts, “employers and elected officials worked together and were able to get the YMCAs open as a drop-off center for children.” In New York “we have worked with the Department of Education, so there’s support for members who bring their children to work.”

The union was also working with unions in other industries to encourage the production of personal protection equipment (PPE). Maria Castaneda describes how her union got connected to the garment workers in the Workers United union and to a hospital in New York. The garment workers were working to produce a plastic face shield for workers. They developed the sample for hospitals to review. The healthcare workers were “excited to partner with Workers United members,” so that they can say “these are union workers helping union workers.”

Bus drivers and other transit workers were also among those most immediately threatened by exposure to the virus. Bruce Hamilton, International Vice President of the Amalgamated Transit Union, said that the union had been aiding its locals to fight for the protection that they really need – “The kinds of disinfectants, the ability to wash our hands, the ability to separate passengers, and to separate people from each other.” He said, “We’re having moderate success in some agencies, but a whole lot more can be done in that regard.”

Hamilton said “We’re fighting for pandemic leave for any of our members who are exposed to the virus” and for “any of their family members that are exposed.” They were also fighting for “eliminating fares during this period,” having passengers on buses “board from the rear door,” and to “maintain separation from each other.” We really need to “maintain whatever distance we possibly can.” So we need to maintain adequate service in those areas “to avoid overcrowding, so you have more buses and more trains arriving so that people don’t crowd all up.”

One thing is clear from these examples: While broad policies and provision of equipment is essential, the nitty-gritty details of making workplaces that are safe for workers, customers, and the public depend on intelligent application of public health practices by the workers on the scene.

Protecting workers’ livelihoods

Some employers and government officials have been seizing on the pandemic as an opportunity to eliminate long-standing protections for workers’ livelihoods, for example by allowing the violation of union contracts and halting NLRB procedures for establishing workers’ right to have an election for union representation.

Gwen Mills, Secretary-Treasurer of UNITE HERE, said “I think the economy is going to be really upside down for a long time.” The union’s main concern for its members at this point was just “the straightforward thing: money, healthcare, food, and shelter.” She said, “Our folks are going to be losing that,” so “we’re going to do all of the work with companies and the governments that we can.” The union had started “direct fund-raising efforts,” but it has also had to start laying off staff.

Mills noted that many of her members work in hotels or stadiums that states are commandeering to turn into field hospitals. “Our members are becoming healthcare assistant workers.” That’s not our industry, but “we’re being pressed into it.” We’re “in the middle of negotiations to try to figure out” how to deal with it.

Bruce Hamilton of the ATU stressed how important it was “to retain employees” and “retain the benefits that they’ve got and their wages.” The recent stimulus package “did some things along those lines” but “there’s so much more that needs to be done and quite a lot of our members are being left out of the picture.” The union has been most successful in “the big, publicly run transit agencies.” Many of those on the East Coast “are not collecting fares now” and are “enforcing social-distancing on our public transit vehicles.”

Hamilton said that “one of the toughest things that we’ve been encountering is dealing with the privatizers.” The ATU has had some success in fighting them. In the Washington, DC area “we just had a pretty long strike that resulted, finally, in a big concession by the authority down there, WMATA, to end the privatization of a part of their system.” This is one thing that “environmentalists and community groups and everybody” can all get together on, “fighting against this awful scourge of privatization that has been seeping into public transit in a really horrific way.”

This crisis shows, better than anything, why privatization just doesn’t work there. We’ve got massive layoffs now. Where our systems have been privatized, workers there have little or no sick leave. In spite of our best efforts, the paid time off is just almost nonexistent. Those systems have lower health and safety standards. They’re looking for profit and not to provide a public service. So that’s a big part of it. And supporting our transit workers, we need to continue advocating for better federal legislation that does extend all those rights.

Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, said the union is trying to make it possible for people to stay away from work if necessary for health reasons and continue to get paid. While the CARES Act is supposed to provide support for this, it was not yet doing so. Looking forward, Weingarten emphasized “all of the economic impacts, short and long term, that we need to address” because of what’s going to happen in this “recession … depression.” She added, “Let’s try to envision how to use this” to create “the society that we want to see.”

Finally, unions played a major role in trying to shape the recent stimulus package – now known as the CARES Act – to be more of a worker protection program and less of a giveaway to corporations and banks. The aviation relief plan provides one example. Sara Nelson, President of the Association of Flight Attendants, said “We just worked really hard to have a labor-centered aviation relief plan, and we actually were able to keep our framework so that people can keep their paychecks going.” The airline industry “didn’t get a bailout” because “we were actually able to take control of this process.” It was a “Workers First package.” For the first time in history, “the corporations are being told exactly where to put the money”; it has to all go to paying benefits to the workers. Nelson hopes this can provide a model for other unions and even other industries that don’t have unions.

Building workers’ power

The pandemic shows it can be a life-or-death matter for workers to have a collective voice in determining their conditions. A major part of union response has been communicating with, providing information to, and mobilizing their membership.

Gwen Mills of UNITE HERE said the union has held “dozens and dozens of Zoom calls with hundreds of worker leaders on them, who talk to their coworkers at work.” That is “how people communicate and provide leadership to each other.” People are

figuring out this technology, figuring out how to stay united as workers, and be able to talk to each other about how to take political action, how to keep fighting employers where they’re not giving us what they should in the layoffs, and just how to keep each other safe. We’re really trying to use this moment to build real community, further community, amongst our membership.

Bruce Hamilton said the ATU “formed a command center at our headquarters at the Douglas Center in Silver Spring, Maryland” staffed by “officers and staff people who can get very quick responses to our members that are fighting out there for their jobs and for protection on their jobs.”

Faye Guenther, President of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 21 in Washington state, said the union has “amped up our communications with our members.” They are doing emails, “daily huddles,” weekly “phone call town halls,” and “emergency hotlines.”

Local 21 has also undertaken two remarkable innovations to reach out to workers who are not members of their union. “We’ve declared ourselves the bargaining agent for all workers, whether they’re union or not,” and are “making demands of non-union employers like Amazon, WinCo, anybody that doesn’t have a union” and are “acting as their bargaining agent.” And because some of the industries they represent were expanding rapidly, they set up a “hiring hall” available to workers from other unions who have been laid off. “We have thousands and thousands of job openings, and we need to help fill them because our workers are getting sick and they’re getting fired, and so we need help.”

Local 21 had also been involved in pushback against the reduction of worker rights during the pandemic. The NLRB suspended all union elections, “which really is just a total attack on democracy and workers’ rights to organize.” Local 21 organized with other unions to demand that workers have the right to a union. “This is the time workers have to have a voice, so that they can speak up at work.” So “we want to make sure that workers have the right to organize” and that “the NLRB immediately re-instates all elections.”

Guenther says the union is trying to “go on the offense in every possible way.” And they are working on a vision document for the future. “We have to stop the bleeding now, but we have to decide what kind of society we want to have post-COVID-19, and what the role of government is, and where workers are going to be at the center of this battle.”

The Essential Workers Bill of Rights

These experiences and struggles led unions to see that the basic demands of those declared “essential workers” and therefore expected to go to work in the midst of the pandemic were largely the same whether they were healthcare works, bus drivers, janitors, factory workers, or firefighters. From that perception emerged the idea of combining these demands into an “Essential Workers Bill of Rights” that would protect all those working during the pandemic, whatever their industry, occupation, immigration status, form of employment, or other characteristics. In discussion with unions and other worker representatives, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ro Khanna crafted the elements needed in an “Essential Worker Bill of Rights” which they spelled out in a Congressional sign-on letter. They include:

- Health and safety protections. Every employee, including employees of contractors and subcontractors, should be able to do their job safely, which means having necessary amounts of personal protective equipment provided by employers at no cost to the employee. Employers should be required to take proactive actions when someone at the job site may have contracted coronavirus, including informing employees if they may have been exposed and evacuating the job site until it can be properly cleaned. And the Occupational Safety and Health Administration should be required to immediately issue a robust Emergency Temporary Standard to keep employees safe.

- Robust premium compensation. Every worker should be paid a livable wage, and essential employees are no exception. During this pandemic, essential workers should also be paid robust premium pay to recognize the critical contribution they are making to our health and our economy. Premium pay should provide meaningful compensation for essential work, be higher for the lowest-wage workers, and not count towards workers’ eligibility for any means-tested programs. It must be retroactive to the start date of the pandemic, and not used to lower the regular rate of pay for any employee.

- Protections for collective bargaining agreements. Collective bargaining agreements must be protected from being changed or dissolved by employers during this crisis, including during bankruptcy proceedings. Workers’ rights to vote for representation in a National Labor Relations Board election in a fair and safe manner must also be protected during the pandemic.

- Truly universal paid sick leave and family and medical leave. Congress must pass Senator Patty Murray’s PAID Leave Act, which provides 14 days of paid sick leave and 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave, so essential workers can care for themselves, family members, or dependents, without being required to submit unnecessary paperwork. And we must ensure that President Trump is not allowed to arbitrarily exclude workers or roll back these protections.

- Protections for whistleblowers. Workers who witness unsafe conditions on the job or know about workplace coronavirus exposure must be able to openly identify their concerns and have them addressed, without fear of retaliation.

- An end to worker misclassification. The pandemic has highlighted the longstanding problem of employers misclassifying workers as independent contractors in order to avoid providing the full suite of benefits and protections available to employees. At a time when too many essential workers are being denied basic employment protections, Congress should crack down on worker misclassification.

- Health care security. All essential workers should get the care they need during this crisis, including those who are uninsured or under-insured, regardless of their immigration status. We must use public programs to provide no-cost health care coverage for all, as quickly as possible. Congress should also listen to workers who have called for a full federal subsidy for fifteen months of COBRA for employees who lose eligibility for health care coverage.

- Support for childcare. At a time when childcare providers across the country are closing their doors and struggling to survive the pandemic, Congress must commit robust funding to help these providers and ensure essential workers have access to reliable, safe, healthy, and high-quality childcare.

- Treat workers as experts. Any time a public health crisis hits, the government should work with employers and workers to craft a response and set safety and compensation standards. Essential workers, and their unions and organizations, must be at the table in developing responses to coronavirus – from determining specific workplace safety protocols to helping develop plans for distributing PPE to holding seats on the White House Coronavirus Task Force.

- Hold corporations accountable for meeting their responsibilities. Congress should ensure that any taxpayer dollars handed to corporations go to help workers, not wealthy CEOs, rich shareholders, or the President’s cronies. That means taxpayers and workers should have a stake in how funds are used, and companies should be required to use funding for payroll retention, put workers on boards of directors, and remain neutral in union organizing drives. CEOs should be required to personally certify they are in compliance with worker protections, so they can face civil and criminal penalties if they break their word. And any federal funding should be designed to ensure that employers cannot skirt the rules by firing or furloughing workers or reducing their hours or benefits in order to access a tax credit or avoid a worker protection requirement.[2]

Many organizations have been demanding that the Essential Workers Bill of Rights be included in the next stimulus package, dubbed “CARES 2.” They include labor organizations like SEIU, the American Federation of Teachers, and the National Domestic Workers Alliance; environmental and climate groups like the Sunrise Movement, Greenpeace, Sierra Club, Oil Change International; and many other progressive groups including MoveOn and Daily Kos.[3] Their campaign featured a Day of Action May 7.

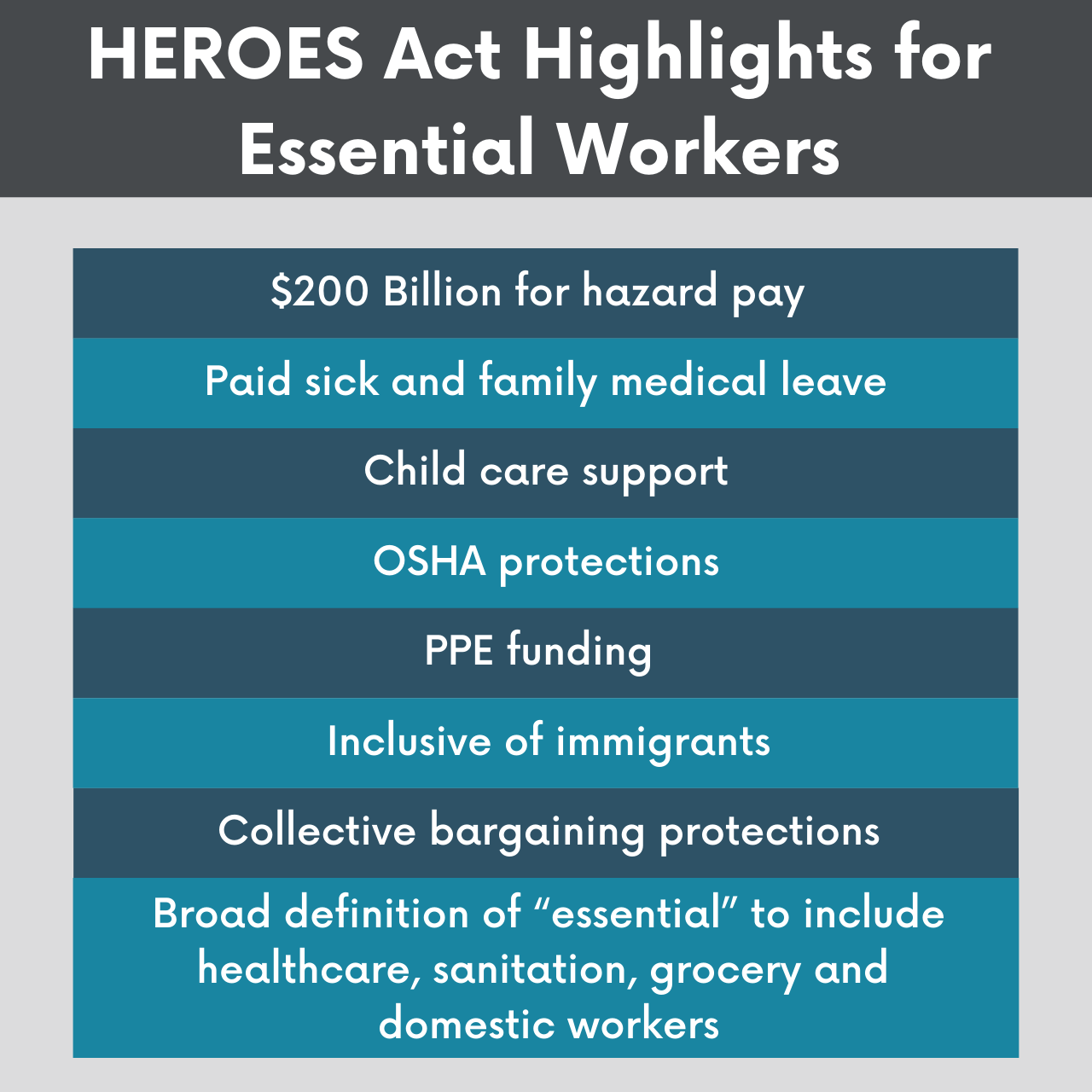

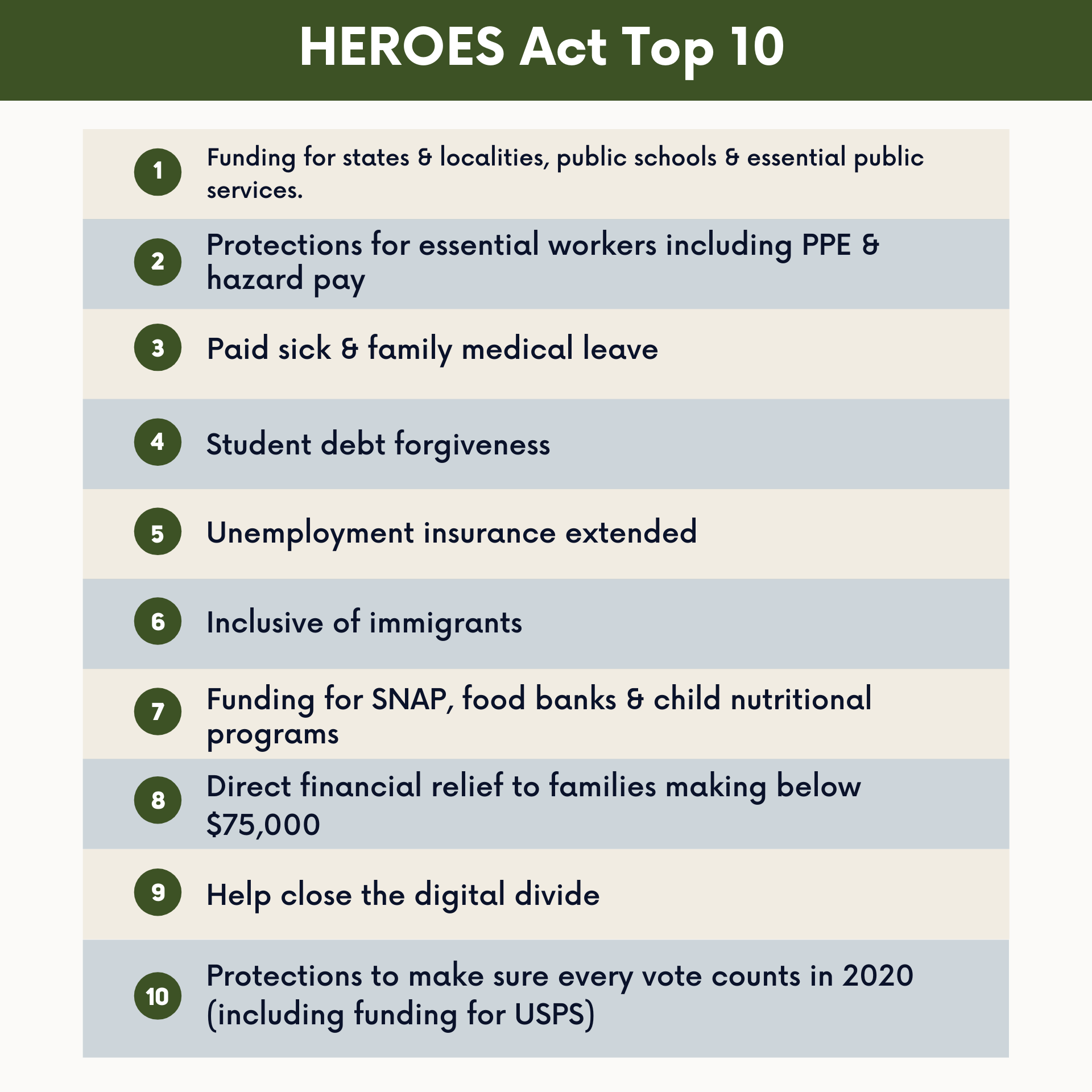

On May 15 the House passed the HEROES (Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions) Act. Thanks in part to the campaign for the Essential Workers Bill of Rights, many protections for essential workers are incorporated in the HEROES Act, including:

- $200 Billion for hazard pay

- Paid sick and family medical leave

- Childcare support

- OSHA protections

- PPE funding

- Inclusive of immigrants

- Collective bargaining protections

- Broads definition of “essential” to include healthcare, sanitation, grocery and domestic workers.

Advocates for essential workers also note that some important elements of the Essential Workers Bill of Rights have not yet been included. The HEROES Act will now go to the Senate, where there is massive Republican opposition to many of its provisions. The final contents and fate of the bill will be determined by negotiations between the two houses of Congress – and by public pressure. A Day of Action to support HEROES ACT protections for essential workers is scheduled for May 21.[4]

The Essential Workers Bill of Rights can play a role that goes beyond federal legislation. States and municipalities are working on their own Essential Workers Bill of Rights; the New York City Council has already held hearings on such a bill.[5]

Whatever happens in the political arena, the Essential Workers Bill of Rights can help give a common focus to the wide range of union, environmental, and other groups that are fighting for essential workers. And it can legitimate and unify the bargaining campaigns and strikes that essential workers themselves are already conducting.

Here is one example: one of the key demands of the Essential Workers Bill of Rights is that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration establish an emergency OSHA standard to protect all workers from coronavirus infection by requiring Personal Protection Equipment and other public health measures. But some states aren’t waiting for a new federal standard: 18 state OSHA agencies have already issued specific guidance on COVID-19 protections, many of which go beyond the inadequate existing federal standards.[6]

And while we wait for a federal OSHA standard, how about drawing up a “People’s OSHA Standard” that all essential workers can demand their employers as well as their governments implement? Any group of workers can begin enforcing some of those standards in their own workplaces. (“Oh, gee, boss, I think my workstation is now supposed to be six feet away from that guy over there. I’ll just stand here while you check with your boss or with a public health official.”) And all of us who have been clapping and putting hearts in front of our buildings to honor essential workers will surely want to let their employers know we won’t buy anything from them as long as they are exposing their workers to disease and death.

[1] A video of the conference, “Building Support for Workers Amid the COVID-19,” is available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KD_zSC3MB70

[2] “Elizabeth Warren and Ro Khanna Unveil Essential Workers Bill of Rights,” https://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/elizabeth-warren-and-ro-khanna-unveil-essential-workers-bill-of-rights

[3] “Sign the petition: We want an Essential Worker Bill of Rights now!” https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/sign-the-petition-become-a-grassroots-co-sponsor-of-an-essential-workers-bill-of-rights/

[4] “Essential Worker Bill of Rights May 21 Day of Action Toolkit” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xnuIT9f4nZu-E846U0j1Q39NhRBLqCK0I0m7BYM-2PQ/edit

[5] Seyfarth Shaw, “New York City Council NYC Council Holds Hearing on “Bill of Rights” for Essential Workers,” Lexology, May 6, 2020. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=d386447b-d753-4a71-acac-506897b36329

[6] “OSHA State Plan Agencies Issue COVID-19 Guidance,” National Law Review, April 23, 2020. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/osha-state-plan-agencies-issue-covid-19-guidance-0

Jeremy Brecher has participated in movements for nuclear disarmament, civil rights, peace, international labor rights, global economic justice, accountability for war crimes, climate protection, and many others. He is the author of fifteen books on labor and social movements, including the national best seller Strike!. He has received five regional Emmy awards for his documentary film work. He is currently policy and research director for the Labor Network for Sustainability.