By Kristin Wartman

The New York Times

May 10th, 2013

The

home-cooked family meal is often lauded as the solution for problems

ranging from obesity to deteriorating health to a decline in civility

and morals. Using whole foods to prepare meals without additives and

chemicals is the holy grail for today’s advocates of better eating.

But

how do we get there? For many of us, whether we are full-time workers

or full-time parents, this home-cooked meal is a fantasy removed from

the reality of everyday life. And so Americans continue to rely on

highly processed and refined foods that are harmful to their health.

Those

who argue that our salvation lies in meals cooked at home seem unable

to answer two key questions: where can people find the money to buy

fresh foods, and how can they find the time to cook them? The failure to

answer these questions plays into the hands of the food industry, which

exploits the healthy-food movement’s lack of connection to average

Americans. It makes it easier for the industry to sell its products as

real American food, with real American sensibilities — namely,

affordability and convenience.

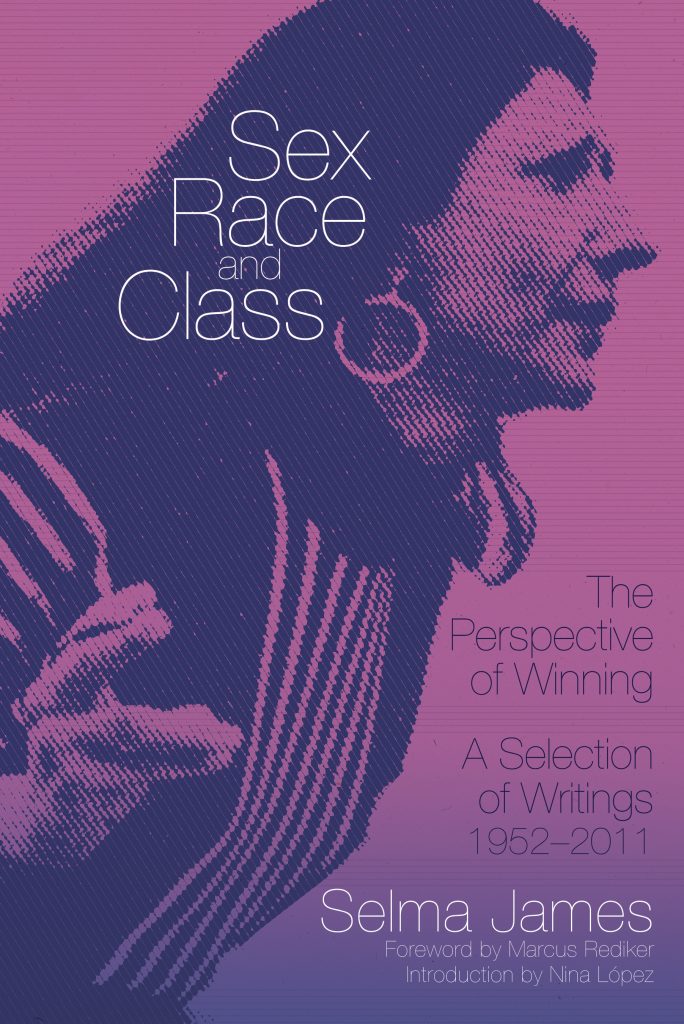

I believe the solution to getting

people into the kitchen exists in a long-forgotten proposal. In the

1960s and ’70s, when American feminists were fighting to get women out

of the house and into the workplace, there was another feminist arguing

for something else. Selma James, a labor organizer from Brooklyn, pushed

the idea of wages for housework. Ms. James, who worked in a factory as a

young woman and later became a housewife and a mother, argued that

household work was essential to the American economy and wondered why

women weren’t being paid for it. As Ms. James and a colleague wrote in

1972, “Where women are concerned their labor appears to be a personal

service outside of capital.”

She argued that it was a mistake to

define feminism simply as equal pay in the work force. Instead, she

wanted to formally acknowledge the work women were already doing. She

knew that women wouldn’t stop doing housework once they joined the work

force — rather they would return home each evening for the notorious

“second shift.”

Many feminists at the time ignored the Wages for

Housework campaign, while some were blatantly antagonistic toward it.

Even today, with all the talk of the importance of home cooking — a huge

part of housework — no one ever seems to mention Ms. James or Wages for

Housework.

But ignoring this idea once again devalues housework

and places a premium on working outside of the home. Since women first

began to enter the work force, families have increasingly relied on

processed foods and inexpensive restaurant meals. Those foods tend to

have more calories and less nutritional value than fresh vegetables,

fruits and meats, so it’s easy to see how the change in meal patterns

led to a surge in obesity.

In 1970, Americans spent 26 percent of

their food budget on eating out; by 2010, that number had risen to 41

percent. Over that period, rates of obesity in the United States more

than doubled. Diabetes diagnoses have also soared, to 25.8 million in

2011 from roughly three million in 1968.

It’s nearly impossible

for a single parent or even two parents working full time to cook every

meal from scratch, planning it beforehand and cleaning it up afterward.

This is why many working parents of means employ housekeepers. But if we

put this work on women of lower socioeconomic status (as is almost

always the case), what about their children? Who cooks and cleans up for

them?

In the Wages for Housework campaign, Ms. James argued for a

shorter workweek for all, in part so men could help raise the children.

This is not a pipe dream. Several Northern European nations have

instituted social programs that reflect the importance of this work. The

Netherlands promotes a “1.5 jobs model,” which allows men and women to

work 75 percent of their regular hours when they have young children. In

Sweden, parents can choose to work three-quarters of their normal hours

until children turn 8.

To get Americans cooking, we need to make

it possible. Stay-at-home parents should qualify for a new government

program while they are raising young children — one that provides money

for good food, as well as education on cooking, meal planning and

shopping — so that one parent in a two-parent household, or a single

parent, can afford to be home with the children and provide wholesome,

healthy meals. These payments could be financed by taxing harmful foods,

like sugary beverages, highly caloric, processed snack foods and

nutritionally poor options at fast food and other restaurants. Directly

linking a tax on harmful food products to a program that benefits health

would provide a clear rebuttal to critics of these taxes. Business

owners who argue that such taxes will hurt their bottom lines would, in

fact, benefit from new demand for healthy food options and from

customers with money to spend on such foods.

If we truly value

domestic work, we should also enact workplace policies that incentivize

health, like “health days” that employees could use for health-promoting

activities: shopping for food, cooking, or tending a community garden.

We

can’t democratize good food without placing tangible value on the work

done in the home. So while proponents of healthier eating are right to

emphasize the importance of home-cooking and communal meals, we will

never create an actual movement without placing a cultural and monetary

premium on the hard work of cooking and the time and skills needed to do

it.

Kristin Wartman is a journalist who writes about food, health, politics and culture.