By Christopher Scott Thompson

Gods & Radicals: A Site of Beautiful Resistance

February 23rd, 2017

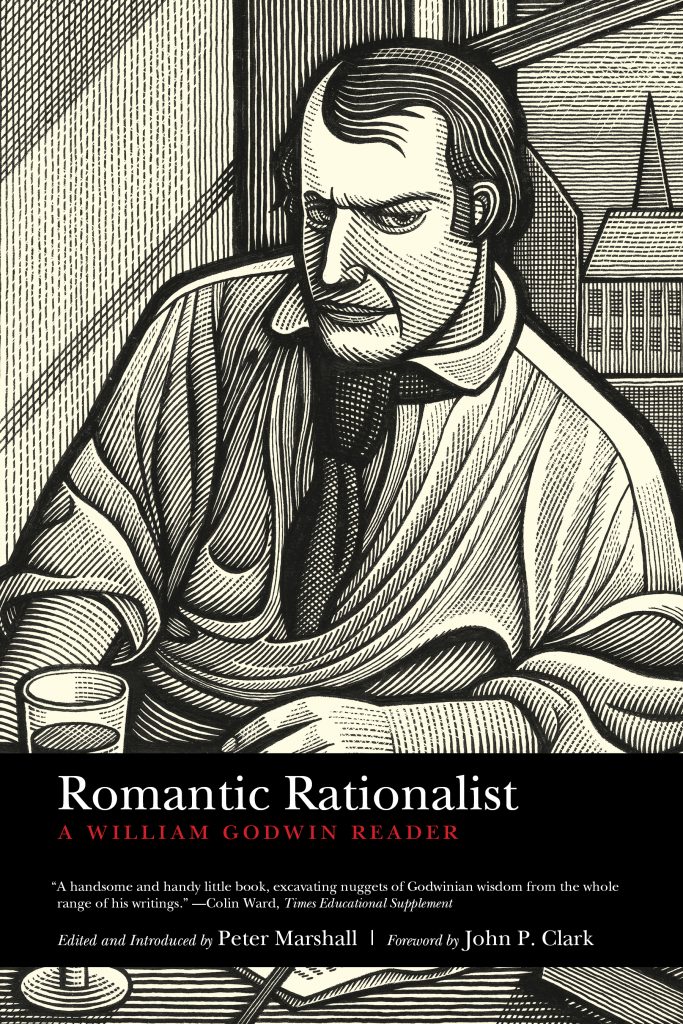

Romantic Rationalist: A William Godwin Reader, edited and introduced by Peter Marshall, is a brief but wide-ranging introduction to the writings of a man who is often considered the founder of anarchism. William Godwin (1756–1836) was the first major philosopher to propose a decentralized directly-democratic society made up of small self-governing communities, and he also anticipated several of the major arguments of later radicals such as Marx and Kropotkin on issues such as private property and the labor theory of value.

If you’re interested in the classical anarchist philosophers but you don’t know where to start, you could definitely do worse than this collection of short passages drawn from Godwin’s works. Unlike Bakunin and Kropotkin, who can be difficult to read because of their frequent references to events and conditions that are no longer current, Godwin expressed himself in general principles. This gives his ideas a clarity and directness often lacking in other works. Here’s his argument against the benefits of government:

The most desirable condition of the

human species is a state of society.

The injustice and violence of men

in a state of society produced the demand for government.

Government, as

it was forced upon mankind by their vices, so has it commonly been the

creature of their ignorance and mistake.

Government was intended to

suppress injustice, but it offers new occasions and temptations for the

commission of it.

By concentrating the force of the community, it gives

occasion to wild projects of calamity, to oppression, despotism, war and

conquest.

By perpetuating and aggravating the inequality of property,

it fosters many injurious passions, and excites men to the practice of

robbery and fraud.

Government was intended to suppress injustice, but

its effect has been to embody and perpetuate it. (Pages 48-49)

Despite

his radical philosophy, Godwin was not a revolutionary like Bakunin or

Kropotkin. He believed that society would steadily improve through

rational discussion and calm debate, eventually leading to the abolition

of the State without revolutionary violence. Many anarchists will see

this as a flaw in his analysis, because Godwin’s approach would force

millions and millions of people to suffer patiently for generations

under tyrannical rule in the naïve hope that reason must eventually

prevail. Despite this flaw, I find Godwin’s calm approach much more

accessible and humane than Bakunin’s fiery apocalyptic pronouncements.

Godwin may also have more to offer pagan anarchists, because major

elements of his philosophy are drawn from the ancient pagan thinkers.

Bakunin was not only an atheist, but a militant materialist and anti-theist. Godwin was officially an atheist too, but in a much more nuanced way. He was an “immaterialist” or idealist, believing matter to be a function of mind rather than the other way around. This unusual viewpoint is most often found among Platonists, and it tends to lead to the vague non-anthropomorphic theism which Godwin apparently adopted in later life. He was also fascinated with the occult, and wrote a Lives of the Necromancers which has probably not been read by very many anarchists.

The influence of pagan philosophy on Godwin is less obvious, but anyone familiar with Epicurus and Epictetus will easily recognize the ideas of these bitterly opposed ancient thinkers in Godwin’s writings. For example, Godwin tells us:

The true object of moral and political disquisition, is pleasure or happiness. The primary, or earliest, class of human pleasures is the pleasures of the external senses. In addition to these, man is susceptible of certain secondary pleasures, as the pleasures of intellectual feeling, the pleasures of sympathy, and the pleasures of self-approbation. The secondary pleasures are probably more exquisite than the primary… (Romantic Rationalist, page 48)

This is nothing other than the core doctrine of ancient Epicureanism. The Stoics, enemies of the Epicureans, accused them of decadence and hedonism because they based their ethics on human pleasure. The Epicureans countered that the highest pleasures were friendship and stimulating conversation, and therefore the true Epicurean was not so much a hedonist as a person who knew how to throw a really great dinner party.

Godwin also tells us:

Justice requires that I should put myself in the place of an impartial spectator of human concerns, and divest myself of retrospect to my own predilections… Duty is that mode of action which constitutes the best application of the capacity of the individual to the general advantage… The voluntary actions of men are under the direction of their feelings. Reason is not an independent principle, and has no tendency to excite us to action; in a practical view, it is merely a comparison and balancing of different feelings. Reason, though it cannot excite us to action, is calculated to regulate our conduct, according to the comparative worth it ascribes to different excitements. It is to the improvement of reason therefore that we are to look for the improvement of our social condition. (Romantic Rationalist, pages 49-50)

Godwin’s claim that reason is “a comparison and balancing of different feelings” is an original contribution (and a convincing one). Everything else in this argument is simply a paraphrase of the core argument of ancient Stoicism: justice is the highest good; reason is the uniquely human capacity to choose between rival claims on our judgment; we can best improve society by making our reason the cornerstone of all our decision-making.

The

Stoics would defy authority rather than obey an unjust order, but in

practice they tended to be politically conservative. The Epicureans were

also a lot more likely to be found hosting dinner parties than putting

up barricades. Yet Godwin somehow synthesized these opposing

philosophies from the ancient pagan world to produce modern anarchism.

If the whole point of society is to improve and increase human happiness

and if this is best achieved when we allow our reason to regulate all

our actions, then the greatest mistake any society can make is to

interfere with the free exercise of our autonomous judgment and thus

interfere with the general happiness. Thus, all systems of government

are both oppressive and inefficient. Godwin may well have been overly

optimistic about the power of reason, but his synthesis of pagan

philosophies produced a vision that remains inspiring: a society of

equality, dignity and autonomy.

Romantic Rationalist includes passages from Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice

as well as his novels and other writings. The passages are organized

into chapters (such as “Ethics,” and “Politics”) and themes (such as

“Duty” and “Rights”) to make it easier to find Godwin’s thoughts on any

particular topic. Editor Peter Marshall is the author of Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism, which is a comprehensive if not massive work. At under 200 pages, Romantic Rationalist is a less intimidating way to dip your toes in the deep waters of anarchist thought.

Christopher Scott Thompson

Christopher Scott Thompson became a pagan at age 12, inspired by books of mythology and the experience of homesteading in rural Maine. A devotee of the Celtic goddesses Brighid and Macha, Thompson has been active in the pagan and polytheist communities as an author, activist and founding member of Clann Bhride (The Children of Brighid). Thompson was active in Occupy Minnesota and is currently a member of the Workers’ Solidarity Alliance, an anarcho-syndicalist organization. He is also the founder of the Cateran Society, an organization that studies the historical martial art of the Highland broadsword.