by Karin Spin

Hip Mama

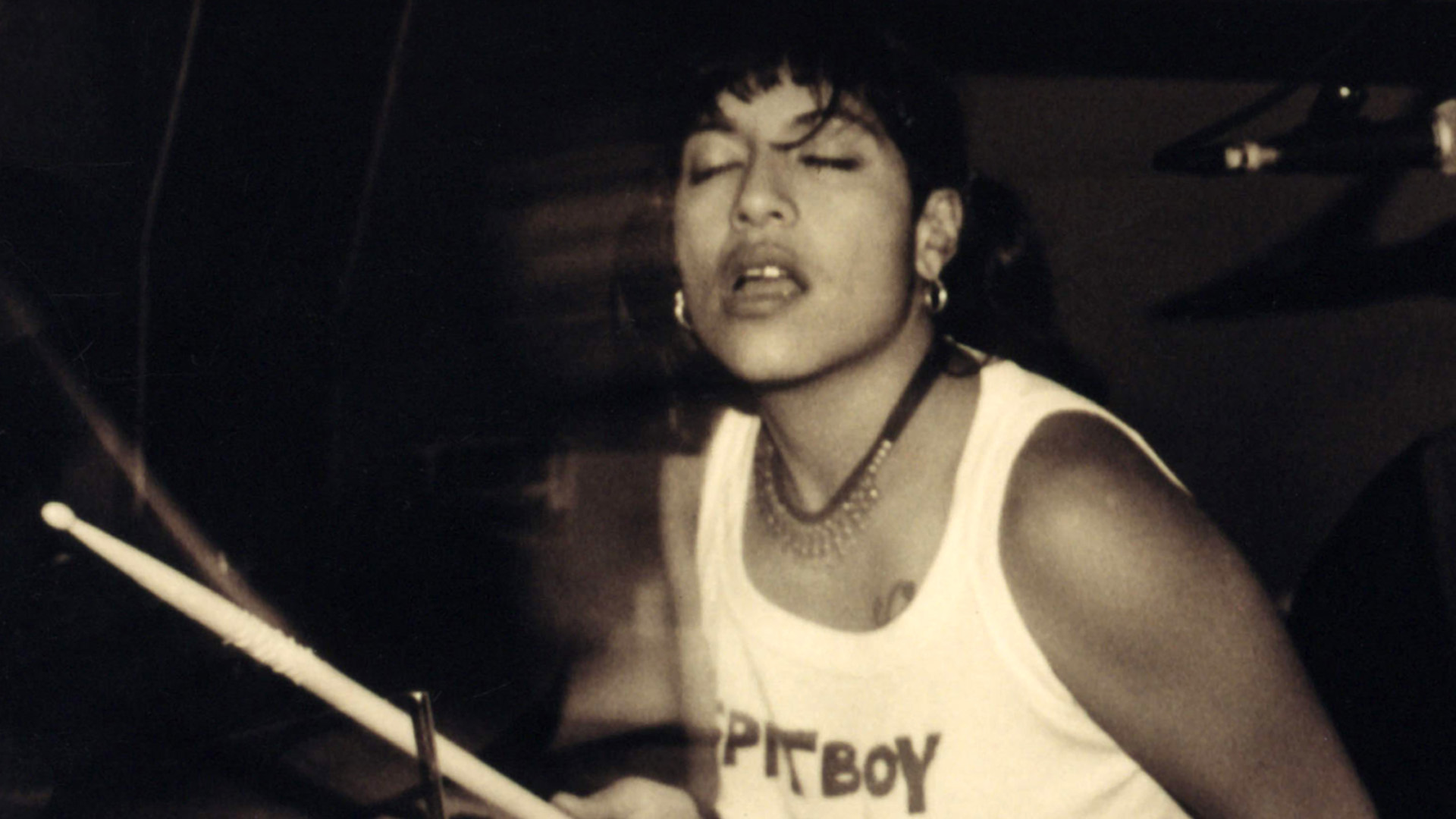

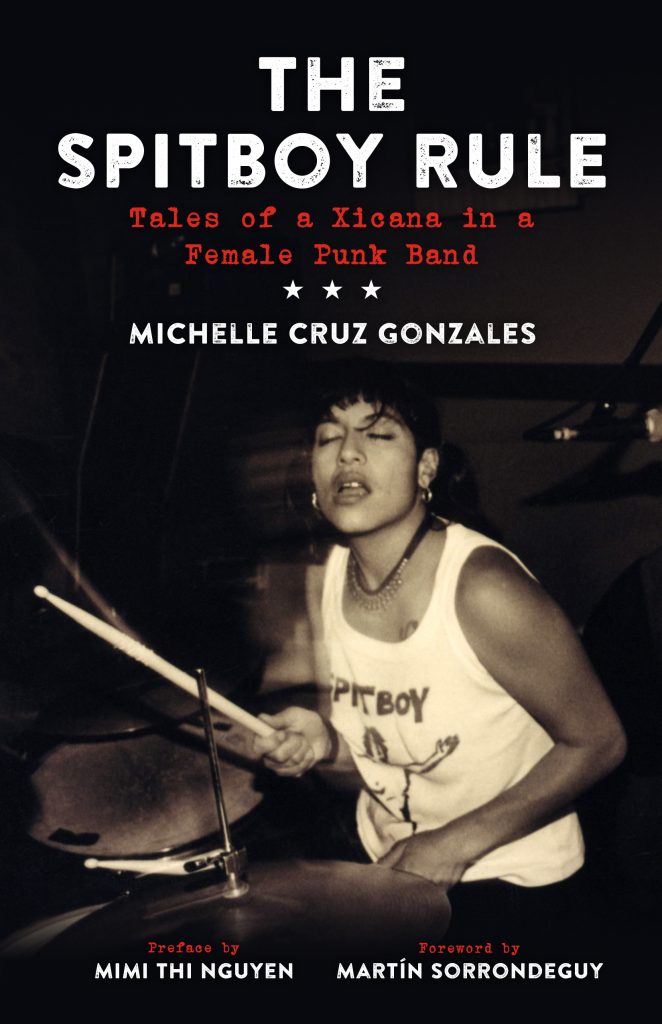

From 1990 to 1995, Michelle Gonzales toured the world as the drummer of Spitboy, a feminist hardcore punk band based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her new book The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band describes her experiences of both finding and losing her identity as a person of color in the punk scene.

She was interviewed at her home in Oakland, California, by her friend and writing partner Karin Spirn.

Karin: You’ve been using the term perimenopunk a lot lately. What does that term mean to you?

Michelle: When I was working on The Spitboy Rule, I was looking at a lot of old photographs and listening to the old bands I used to listen to. I got a record player and I started listening to some of the old records I still have that you cannot listen to on Spotify or Itunes, that you can’t even get on CD. I started going through my archives of Spitboy and related bands and music and clothes and photographs. It revived in me this aesthetic and this value that was always there but I sort of set aside when I was in graduate school and had my son. I just didn’t have time for fashion, for caring that much about a certain look. I cared about nursing my son and getting good grades in my writing classes. Punk took a real backseat. Writing this book made me see just how much punk is a part of my life no matter how close to it I am at the time.

And then I started going into perimenopause and having these exact same feelings of frustration about the world that I had when I was sixteen. Being sick of people telling you what to do, defining you, belittling you. Now it’s not people belittling me because I’m young and have no power. It’s because when you get older, people stop seeing you. You become invisible.

You are not taken as seriously. Perimenopunk is about going into middle age and not feeling like I have to abide by rules about what it means to be forty-seven, forty-eight, forty-nine, fifty.

I don’t have to not dress like a twenty-year-old. If I want to die my hair I will; if I don’t want to, I’m not going to. At every age you’re expected to fit the society’s idea about what you should look like and what you should wear and how you should act. Perimenopunk is a nice way to remind me not to get boring and to continue being outspoken.

Karin: Your first memoir, Pretty Bold for a Mexican Girl: Growing Up Xicana in a Hick Town, was about your childhood in Tuolumne, California. I wondered how that book is different from The Spitboy Rule in terms of its themes and your writing process.

Michelle: I actually think they’re really similar. The second half of Pretty Bold for a Mexican Girl discusses how I got into punk rock, how I started my first band when I was fifteen, and why I was attracted to a subculture movement that was political and that helped me express my feminism. It also helped me express a frustration that people were always foisting an identity on me. I was like, I’m gonna form my own identity, dammit, and I used punk rock to help me.

So The Spitboy Rule picks up where Pretty Bold leaves off.

I did write new things about Tuolumne in The Spitboy Rule. I really love writing about Tuolumne. Where I grew up, the small town, really has so much to do with forming my identity.

It was a horrible place to grow up, but interestingly a very comfortable place to write about.

In terms of the process, I was learning how to write memoir when I wrote Pretty Bold for a Mexican Girl. I studied fiction at Mills College. I left thinking I was going to be some fancy literary fiction writer, and the first longer work I started writing ends up being nonfiction, the very thing that I didn’t take a single class on. So I had to read a lot of memoir and do a little studying of how to write memoir.

The Spitboy Rule was a different process because I felt more confident, more like I knew what I was doing. Also I had a very clear audience in my mind that I didn’t quite have for the first book. For the first book, my audience was mostly, like, me, I guess. For the second book, my audience was Spitboy fans, Latino punk rockers and people who like music.

Karin: One of my favorite stories in the book is “Mi Cuerpo Es Mio,” which is about people not recognizing you as Mexican-American during your time in Spitboy. The book, then, is a kind of coming-out as a Xicana. I wonder how people in the punk community are reacting to that.

Michelle: Nobody has said, “Oh, you never talked about that then. You’re just making this up, because now being a person of color is something you get cache from.” But I suspect that some people would think that, and it might be a fair thing to think. I mean, rude and presumptuous, but kind of fair. I may have, at points, not appeared interested in my identity. I may have appeared more interested in being punk rock or feminist or part of a band or the scene. After growing up and not fitting in, when you start start fitting in somewhere, you’re like, this feels pretty good. So I went through a phase of really wanting to just fit in. Though I always felt like I didn’t. I felt like a poser a lot of the time. When people started not really seeing my identity, it made me realize: I feel like a poser and this is why. I feel like a poser because I am in a mostly white punk scene that privileges mostly white stuff, and I am participating in that by not being more vocal or clear or respectful of my other identity—of my other identities.

But I think that part of the book is being received well, for a couple reasons. One, there are a lot of Latinos who want to see themselves in literature and movies and punk bands and winning Oscars. Those things aren’t happening enough. Latinos in the United States are becoming the majority and we still are subject to stereotypes and invisibility. I think the punk scene is hungry for other perspectives. The idea that there have always been Latinos and people of color in punk is totally true. We just weren’t as noticed.

Karin: Through your book, and through your teaching in a community college, you’re a role model for young Latinos and Latinas.

Michelle: Well, nobody tries to be a role model. Somebody posted on the book’s Facebook page, “Thank you for being a female drummer and being in a feminist band.” Essentially a role model, though I don’t think they used those words. My reaction was: someone had to go first. I wasn’t trying to go first. I was just trying to do the thing that I loved, to express myself, to be heard.

That desire to be heard is rooted in being Xicana and growing up in a small town and being on welfare and just feeling marginalized when I was younger.

The thing I like about being a quote-unquote “role model” is having the opportunity to be in a room with young people and say, look, it’s really important to think critically and to not be taken advantage of, and to give them some tools to do that. We did that in Spitboy, and I’m doing it in the classroom. I went to community college, and it was really important to have the people to mentor me, instill faith in me, help me see that intellectually I had what it took to be successful in school. I only want to be a role model if I’m in the trenches, if I have some kind of active part in somebody’s life, not some photo on Instagram.

Karin: Do you think your experience would have been different if you’d been in an all-Latina or all-Xicana band?

Michelle: I think it would have been different because I was sort of in that band before Spitboy.

In my earlier band, Bitch Fight, Nicole and I were both Mexican, both Xicanas, and then Sue was a white woman but a single mom on welfare. The class and race differences were almost none in Bitch Fight. We fought a lot, and that’s why we had that name. But the fighting had nothing to do with race or class. The fighting was about being young and immature, and we all grew up together.

So I do think it would have been different, but it’s not like we didn’t have our own problems in Bitch Fight. Because being in a band is hard. You have to collaborate to write songs, to write lyrics and music. People always say that being in a band is like being married, and it’s true, but it’s like being married to two or three other people. Which, you know, being married to one person is hard enough. So you’re having to navigate all these different relationships and egos and learn how to put your own ego in check. Like when you’re writing a song, you always feel insecure when you bring something new to the band. Then how they react to it makes you feel either really good, or just fine, or terrible. You’re really putting yourself out there. You have to share your art with someone else in order to collaborate, but then you’re always insecure at first, when it’s not formed. Those are the kinds of things that make being in a band really difficult.

So in one way, yes, it would have been different. Would it have meant there would have been no problems? No. Because being in a band is just kind of tricky.

Karin: How is being a writer similar to or different from being in a band?

Michelle: I don’t think I could have been as ambitious of a writer as I am, and as brave as I am, if I hadn’t been in the band. When you’re in a band, once you collaborate to create a song, if it’s not exactly what you wanted it to be, you can say, well, I wasn’t the only one who put this together. It didn’t turn out exactly how I wanted it to, but now it’s a band piece—or it’s a band problem. But either way, it’s a collaboration, so I don’t have to take full responsibility. But when you’re writing on your own, it’s all you. If there’s a typo or repeated words that you didn’t catch that you see later—it’s more personal. It’s just you and your name and nobody else.

On the other hand, for me, playing music when I did and writing now serves the same creative purpose for me. I don’t necessarily like one more than the other. I do think I was always more of a writer than I am a drummer. I wrote about half the lyrics in the band, then went straight from doing that to college to study writing. I always liked English more than anything else, like in high school for example. So I do think that I was always more of a writer than a musician.

And I don’t feel weird about that. Spitboy wasn’t trying to be virtuoso musicians; that wasn’t our aim. Spitboy was a band with a message. We were message-first, and music was secondary to the message. Music was the delivery vehicle for the message. Thinking about where I went from there to become a writer, it makes sense. The message is still the thing that’s most important to me.