By Kate MacDonald

March 24th, 2106

The carefully managed outbreaks of magical realism are what I like best about J J Amaworo Wilson’s Damnificados. Wilson’s skills as a novelist are impressive, and his scope in Damnificados is global: his vision of a Latin American city that casually and fleetingly connects to Africa and Japan makes this novel a world myth with a mildly fantastical dystopian setting. It’s set in a vast tower block in an unnamed Spanish-speaking city of favelas and spiralling shanty-towns. The tower is inconveniently inhabited by wolves when a travelling group of hundreds of the homeless underclasses need it as a refuge and a home. They’re led by Nacho, a small man with a dragging leg and arm who moves about expertly on his muletas. He’s a teacher, but becomes a legendary leader of the people against the forces of nature, and against the heavily armed Torres family, who want their tower back. The damnificados, the despised, spurned, rejected and repressed, become a community in their new home. They set up shops, a bakery, a hair salon, start schools, keep watch on the surrounding country and city fringes, and become settled enough to go back into the city to pick up their old jobs again, now they have a home and a clean shirt to wear in the morning. All this is reassuringly human, something to hang onto as the strangeness of this world reveals itself.

The

two-headed wolf leading the pack who originally inhabited the tower:

radiation mutation? Or simple mythic throwback? Either way, we’re now in

magical realism territory. How the damnificados dispose of the wolves

was a fine piece of character development that sets the tone for the

novel: no unnecessary violence, no cruelty, no rampant body counts

unless absolutely necessary. The wolves come back when they’re needed,

so there is also tidy storytelling, nothing left dangling or undealt

with. The giant snakes are important, as are the crocodiles who come

with the floods, and the five immense carved heads that appear at the

city gates when the floods recede. Wilson’s characters are effortlessly

individual: the giant man they call the Chinaman who never speaks,

Nacho’s big brother Emil the picaresque traveller (who will surely be

played by Chris Pratt in the Hollywoodisation of this novel), the

engulfing passion of Maria the ex-beauty queen and salon owner, Shivarov

the creator of bespoke limbless beggars, and Nacho himself, a character

who unpeels a new layer with each chapter.

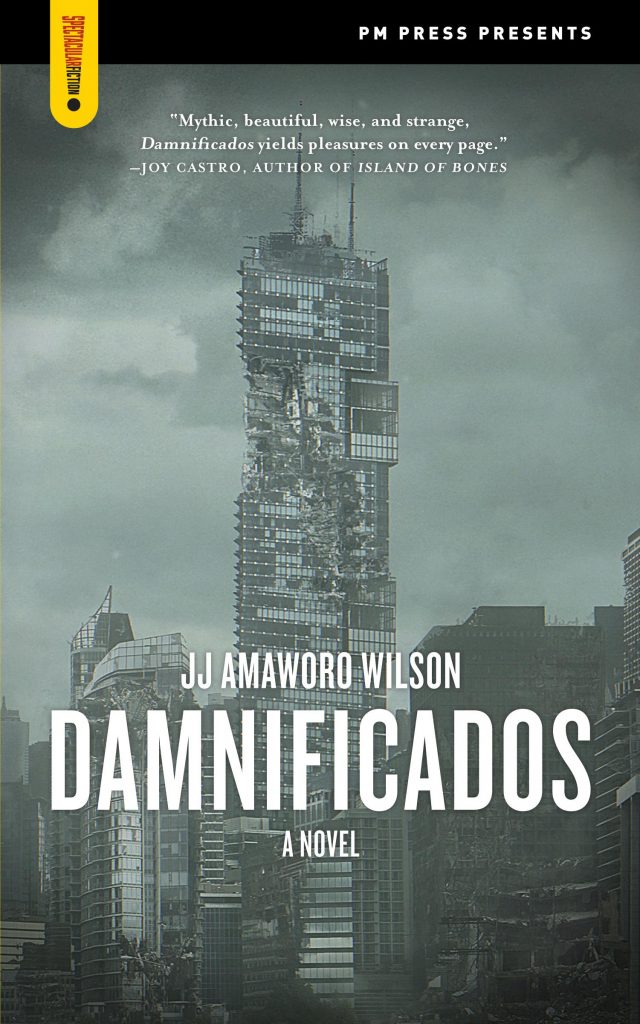

artwork by Peter Garcia to illustrate the novel

He’s a teacher, a leader, a community organiser, he knows his poisonous mushrooms and can recite the history of the world. He loves secretly, does nothing about it because he fears her rejection, and worries constantly about the safety of his people. He’s an angel with crutches for wings and abstruse survivalist knowledge, and speaks heaven knows how many languages. However, his impairment is taken away from him through an unspecified transcendental miracle, as if to reward him for his goodness. I find this reward out of nowhere rather odd, and troublesome in how we are expected to feel about Nacho. The removal of his bodily impairment tells us that such a physical difference isn’t suitable, is in the way of true love (not that the miracle gets him anywhere), and will have to be changed before Nacho can achieve whatever he wants to achieve. It’s certainly a fantasy. People in the real world live with difference without the hope of a miracle and an overnight restoration of muscle tone, nerve endings and bones to what society thinks is normal. Giving Nacho a transformative reward is perfectly suitable within mythic storytelling patterns, but this particular reward feels superficial. It produces a similar effect to narrating the novel from a (mostly) male perspective. Only two women are named, or have anything to say; the world of the damnificados is a man’s world where women are faceless and voiceless, ignored and of no account. Nacho too becomes anonymous when the essential part of his body that has shaped his personality is taken away, he runs like anyone else, and fades from view. His difference has been taken away, which seems a pity, since, within the novel, his difference made him individual.

Damnificados is based on the real events in Caracas, Venezuela, when an abandoned tower block was temporarily inhabited by hundreds of outcasts for seven years. Wilson added the multilingual ghosts and the avenging two-headed wolves, obviously.