by Luther Blissett

Medium

December 18th, 2016

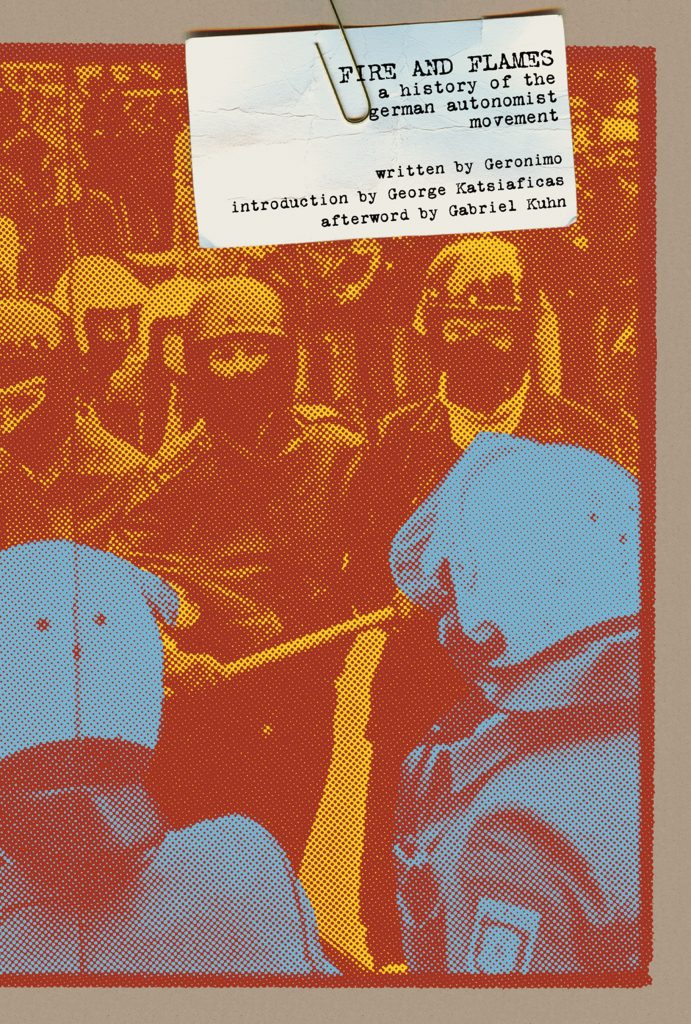

A classic German text about the history and emergence of the Autonomen, Gabriel Kuhn has provided the English reading world with access to this engaging text. Initially published in 1990, various versions emerged; this is a translation of the fourth, the 1995, edition.

Just over 180 pages, the book is engaging and filled full of interesting and fascinating details.

The book is a collection of vignettes. There are reproductions of flyers, posters, and publications from specific protests that are discussed through the book. Multiple short narratives about specific demonstrations, players, or challenges are also presented. Geronimo capably shifts between close reading and returning to the larger picture. Based on his representations, it appears as if this same challenge has been an ongoing challenge for the Autonomen as well: the ability to retain a set focus or to remain a life-long movement.

Honestly, I am not sure whether the Autonomen’s value would be enhanced by being a life-long movement, something that people would commit there lives and energies to for their whole life. That seems problematic at best–especially when you review the “Autonomous Theses 1981” (included as an Appendix). Then again, the very nature of the Autonomen appears to be doing what is right, then and there, for personal liberation and the liberation of others.

Geronimo’s history provides a properly detailed map for understanding the contexts in which the Autonomen emerged without having to fully know the history of West Germany, the intricacies of leftist politics, or the challenges of organizing. Geronimo’s summaries are deft and efficient. The material is easy to read. And there is no question of when critique is included. That’s not hidden.

For North Americans, or at least residents of the USA, some of the protest and demonstration descriptions might seem fascinating or odd. First, given the sheer numbers involved in some of the property-destructive demos. Second, given the completely different ways that contemporary law enforcement responds to Black Blocs and other groups that intentionally destroy property. As such, the book can help readers see another way that a culture could manage protest and resistance. However, at this point in the game, you can’t turn back the clock.

Probably the best part of the book is the overview it provides. While the Autonomen, rarely featured in North American press except perhaps in reference to Black Blocs, are not as well known as they might be, they cannot be reduced to the simple smash it up narrative which corporate media in Germany has tried to do to them for three decades. While one could assert, quite persuasively, that Black Blocs emerged from the Autonomen, Black Blocs are more of a strategy, a tool.

Just like Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs?, Fire and Flames presents a rich, complex, and accessible path to understanding not just who and what some of the Autonomen are, but why they do what they do. Readers need not agree with any or some of the text. However, simplistic castigation of property destruction or internal wars against the rich or ruling elite as thoughtless violence can’t hold water after reading these texts. Yes, there will always be thoughtless fools who agitate for violence. How many more volunteer as mercenaries for Capital, to wear the State’s uniform?

If a broken window costs several thousand dollars to replace, is it better to have an officer break a protestor’s jaw, smash their teeth, or send them to the hospital for several days–all injuries that will result in tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills? So, once again, corporate profits and property are protected while the losses and damages are dealt out to citizens to pay.

Perhaps the least accessible portion of the book, for this reader at least, was the apparent endless in-fighting and factionalization around various Marxist, Leninist, and ecology-related threads. It does not take too much imagination to translate such factioning in the US context; however, the specifics were not familiar to me. Similarly unfamiliar was the control that some militant political parties expected, and perhaps still expect, in individuals’ political and personal lives.

What the author, and some Autnomen, apparently posit as a problem–the inability of Autonomen to remain involved for a long time–does not strike me as a problem. Instead, the role of Autonomen, their approach and paths, strike me very much like the Black Blocs: they are a strategy that is appropriate and viable for specific people in specific contexts. At some times, it may be most useful to support anti-imperialist or anti-fascist struggles and to work within those movements. However, conditions may change, internally or externally, when Autonomen need to emerge. That is the apparent beauty and freedom of the movement, the gift and the curse: the ability to be when needed and not be when not needed.

A final note: much of the Autonomen’s rise, and ongoing connection with local and national struggles, was rooted in their engagement around housing, squatting, and struggles for affordable, and free, housing. Reviewing the USA, it is difficult now to not see how this issue, affordable housing, could be an incredible gateway for widespread activism and engagement.

While

some aspects of it definitely support and continue to feed Finance and

Capital, at the same time, if such struggles lead to higher quality

lives, and better and more affordable shelter, then it seems worth

pursuing.

Back to Geronimo’s Author Page | Back to Gabriel Kuhn’s Author Page| Back to George Katsiaficas’ Author Page