By Patrick Jordan

Catholic Worker, NYC

March 2015

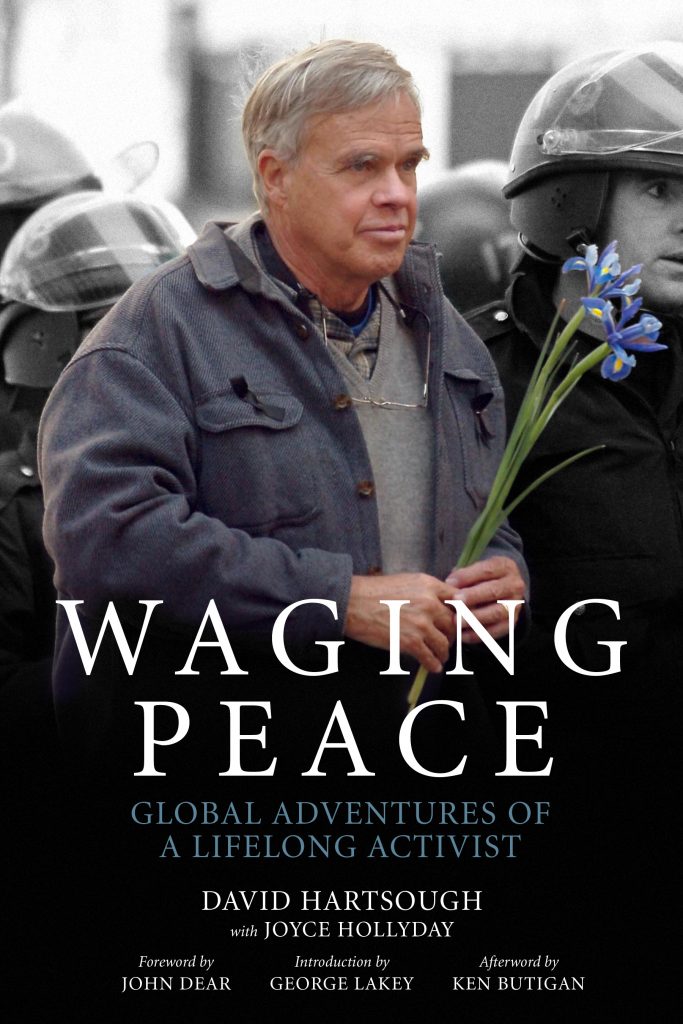

If Ammon Hennacy were around to update his 1970 posthumously published The One-Man Revolution in America,

he would likely add a chapter on David Hartsough (b. 1941). For nearly

sixty years, this Quaker-inspired activist has resisted war, racism, and

injustice at home and literally around the world. Hennacy’s book was a

veritable Profiles in Courage for America’s unsung peacemakers and radicals. In Waging Peace,

David Hartsough brings that tradition up-to-date by forty years, every

year of which includes his actions of protest and courage.

This

autobiographical record begins with David’s Ohio roots. His mother was a

first-grade teacher and an activist, his father was a Congergational

minister. At age seven, young Hartsough faced down a group of town

bullies who had bloodied him. Later, he sought out—and became friends

with—their jefe.

From there the story moves quickly to

Pennsylvania, where the teenage David organizes his first peace protest

(at a Nike missile site); then to Virginia, where the angered patron of a

segregated lunch counter David and others were attempting to integrate

threatens his life; and then on to the White House, Berlin, Red Square,

and even the Holy Land, all places where he demonstrates nonviolently

for reconciliation. The book concludes half a century later, with his

arrest outside a U.S. drone base.

I got to know David (a fitting

name for one taking on Goliaths), his wife Jan, and their two small

children in 1970 at Pendle Hill, the Quaker Study Center outside

Philadelphia. He had just completed an arduous, five-year stint as a

national organizer for the Friends Committee on National Legislation.

Little did I know, until reading Waging Peace, that in that

capacity he had organized many of the huge antiwar demonstrations

Catholic Workers and others had taken part in during the 1960s; or that

before that, his father had worked with Martin Luther King Jr.; that

Bayard Rustin had encouraged David to enroll at Howard University in

Washington, D.C., and that in 1960, with fellow student Stokely

Carmichael, he had led protests for integration in Virginia; or that as

part of a 1962 Quaker delegation, he had met with President John F.

Kennedy to call for a national policy of “waging peace”: the inspiration

for this book’s title.

David first came to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI at age fifteen. In fact, Waging Peace

reads like a chronology lifted from his FBI file—a lifetime of

protests, arrests, and agency misperceptions concerning David’s actions

and motivations. It’s not hard to see why. There are his Quaker summer

work camp in Cuba (1959), only months after Castro overthrew the

U.S.-backed dictatorship of Batista; David’s experience in Communist

Yugoslavia the following summer (he would return again in 1997,

attempting to reconcile warring Serbs and Kosovars); his junior year in

Germany (1961), auditing classes at East Berlin’s Communist Humboldt

University; and summer forays for students he organized to Eastern Bloc

countries and the Soviet Union in 1961 and ’62. There, David was nearly

arrested in Red Square and threatened with twenty years in prison for

demonstrating against nuclear testing. Back in the U.S., he was arrested

outside the White House during a similar demonstration. In one

instance, he was released from jail in the nick of time to accept his

college diploma. Then came alternative service as a conscientious

objector, a master’s degree in international studies at Columbia, five

rewarding but hectic years in Washington, D.C., with Quaker lobbying

groups, and marriage and a family.

Here is where the story

gets particularly interesting and challenging for someone like me, close

to David’s age and with a similar family constellation. For during

David’s time at Pendle Hill, he and Jan decided to continue following a

path of protest and simple living that would allow them to take risks in

the service of peace and to resist paying the federal taxes that go for

military expenditures (over 50 percent of the annual discretionary

budget). A simple lifestyle, often shared with other like-minded

families in community, allowed the Hartsoughs to live below a taxable

income for many years. When they did exceed that minimum, they made it

difficult for the IRS to extract its blood money. The IRS threatened to

confiscate their home, but eventually settled for garnishing a savings

account. For over forty years, the Hartsoughs have been able to resist

paying war taxes outright; during the same period they have welcomed

countless guests, all the while remaining exemplars of sane and caring

resistance.

Ammon Hennacy would be particularly impressed with

the long, consistent list of David Hartsough’s protests, fasts, and

jailings. They include organizing several peace flotillas to block free

passage of munitions ships during the Viet Nam War; helping form the

Abalone Alliance (1977-84) to impede completion of the Diablo Canyon

nuclear power plant; protests and arrests at the Lawrence Livermore

National Laboratory (1981-83). These were followed by years of actions

against U.S. counterinsurgency policies in Central America, based on

David’s own fact-finding trips to the region. He personally accompanied

threatened villagers in Chiapas, Mexico, as well as Guatemala,

Nicaragua, and El Salvador. In 1987, he and others pledged to disrupt

weapons shipments to Central America from the Concord Naval Weapons

Station in California.

In one of those protests, his good friend

Brian Willson was run down and nearly killed by a munitions train. The

callousness of the event, and David’s assistance to Willson, then and

for many years after the train had severed Willson’s legs, make for

heart-pounding reading. “The war came home in a powerful way that day,”

David recounts. “What our government had long been willing to do to poor

people and people of color in other parts of the world, it was also

willing to do to peaceful protesters in the United States who tried to

impede the war effort.”

Here, as elsewhere, David reflects on

the necessary courage of those who would wage peace. The Concord protest

lasted 875 days. David was arrested repeatedly, but, he writes, “an

amazing, inspiring community grew up around the Concord tracks,” one

that included ex-CIA agents, many war veterans, and even his own aged

and infirm parents.

David later traveled to the Philippines, the

Soviet Union, Iran, and the former Yugoslavia; and served as executive

director of the activist group Peaceworkers. In 2001, he co-founded the

Nonviolent Peaceforce with Mel Duncan. Its aim is to send teams of

nonviolent “soldiers” into war-threatened areas to short-circuit

violence and offer peaceful models of resolution. David’s arrest in

Kosovo in 1997, under orders from Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic, is

another heart-palpitating episode in this inspiring chronicle. For

David, nonviolent protest for change is never on the cheap. The

Nonviolent Peaceforce has now fielded support groups in over forty

countries, and has received growing recognition and support from the UN

and the European Union.

In his final chapters and appendices,

David provides further stories of successful nonviolent campaigns and

offers resources for those wishing to challenge the status quo. He finds

hope in living near his own grandchildren; contact with them, he

writes, “renews our commitment to helping build a world in which all

children can look forward to a future of peace and justice.”

If

anything might have further enriched this book, it would have been to

include more about the author’s own inner geography: the effect of the

storms he experienced on his inner thought and person. Further, the

macro geopolitical landscape alluded to here relies almost entirely on a

“Democracy Now” point of view. For many readers that will be a high

compliment, even an endorsement; for others, it will seem an unnecessary

but limiting liability. For those who don’t know David Hartsough in

person and have not experienced his hearty, self-deprecating laughter,

his purity of spirit, and his hospitality, that might diminish this

exemplary autobiography. That would be a loss for our times, so in need

of exemplars and “one-man revolutionaries.”

Waging Peace

is a book that challenges, inspires, and offers hope: all gifts that

will endure and even transcend the heroic witness of its remarkable

author.