By Dr. Lenore J. Daniels

BlackCommentator.com

Feb 1, 2012

Issue 457

There’s no escape . . . There’s only what you do.

—Catholic Monk to James Orbinski, Doctors without Borders

My heart’s in this struggle. My people will overcome. All the peoples will overcome, one by one.

—Pablo Neruda, Canto General

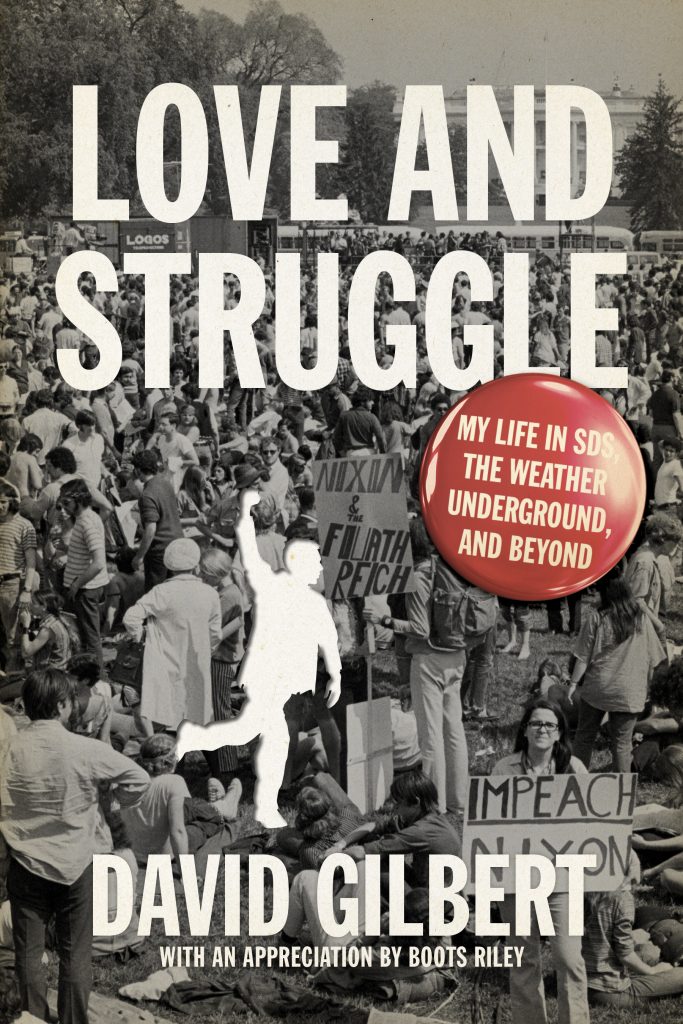

I was eager to read Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground, and Beyond, but apprehensive too. Review a book written by an imprisoned ex-member of the Weather Underground (WUO). I knew of David Gilbert, and of course, the WUO, Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, Mark Rudd and others, activists who split from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) to engage in armed struggle “underground.”

When I left Operation Breadbasket in Chicago, not long after the organization split from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), I had had enough of the Christian, conservative, don’t-rock-the-boat, reform is good mentality of the mainstream Blacks. I was trying to remain committed to the revolution and the tasks of resistance ala Fanon, Freire, Guevara—while a Black woman—at a predominantly white college campus in Illinois, knowing that the misogyny of more radical Black organizations would be as oppressive as those State forces who murdered Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

In the years of WUO’s bombings of State buildings, I followed the news of the latest arrest or murder of Black activists or Black Panther Party members. Tread carefully above ground was the message my generation of Blacks received from the State. The struggle for Black liberation in the United States is over! We are simply rounding up the excess “waste,” picking up the corpses. Respond with anything other than a blank expression, and we’ll know. We’ll know . . .

I had not read anything written about or by Gilbert, nor had I listened or read an interview he had given the past. I expected a typical self-aggrandizing narrative in which the passive reader encounters the “greatness” of the man David Gilbert and his “legendary” role in piecing together pipes and wires, sneaking here, passing that guard and boom! Good ole’ boys at the usual, historically Western, good ole’ boys stuff . . . But no! This is not Gilbert’s narrative.

This narrative reveals an author who is still profoundly commitment to revolutionary change—and who is not, frankly, an obnoxiously white man in the business of glorifying his or the white support network’s past activities on behalf of people of color.

Before he is eligible for parole, Gilbert needs to reach his 111th birthday, and he is sixty-eight years old, a political prisoner at Auburn Correctional Facility in New York, serving a life sentence. Gilbert is not apologetic for his commitment to the Struggle and there is a struggle continuing, one that Gilbert clearly understands never ended, as it has for so many white and Black “activists” of the 1960s and 1970s era.

If anything, the liberal, young, white, middle-class Columbia University student who wants to be helpful at first, who observes older organizers, the poor and the Black, who debates the level of commitment necessary for revolutionary change, and then who determines that commitment to radical thinking and activism will be for him a way of living personally and publicly among his fellow human beings, made costly blunders in judgment and remained silent when he should have openly expressed his concerns.

There are no mistakes. The events we bring upon ourselves, no matter how unpleasant, are necessary in order to learn what we need to learn; whatever steps we take, they’re necessary to reach the places we’ve chosen to go. (Richard Bach, American writer).

Love and Struggle is David Gilbert’s work! It is Gilbert’s work for readers and activists. It is a dialogue, and, if we are serious students of movement organizing, then reading Love and Struggle becomes a way to critically engage in a dialectic dialogue with a fellow fighter and lover of human rights. And for that reason and more, it is a must read for anyone active in the process of building an anti-capitalist and an anti-imperialist movement.

“Measured by either standard—full solidarity with the Third World or support by a majority of white people—the WUO was a failure.”

Recalling a collective of “internal discussions” at WUO meetings, Gilbert writes that the five main aims of “armed propaganda” had been to:

1) draw some heat so that the police and FBI couldn’t concentrate all their forces on Black, Latino/a, Native, and Asian groups;

2) create a visible (if invisible!) example of whites fighting in solidarity with the Third World struggles;

3) educate broadly about the major political issues;

4) identify key institutions of oppression; and

5) encourage white youth to find a range of creative ways to resist, despite repression.

These aims could be considered “abstract today,” Gilbert writes, since armed struggle is off the agenda of the “anti-imperialist movement in the U.S.” But at the time, he continues, these aims “resonated and even had a certain urgency . . . when revolutionary struggles were raging throughout the world.” But Love and Struggle suggests that these aims should not be “abstract” today.

Revolutionary struggles are raging throughout the world: The Arab Spring uprisings and Europeans and U.S. citizens are in the streets!

The FBI’s COINTELPRO operation has not disbanded, but expanded into the Patriot Act, Homeland Security. The most recent indefinite detention law (NDAA) is war against civil liberties at home. The disconnection between the American Dream of white Americans and the institutionalization of repression experienced by people of color within the United States, is acknowledged by the young adults today, and once again, the aims of radical struggle no longer seem “abstract.”

It was not the aims but the forces, both internal and external, that sent the white activists back to their familial homes and liberal pursuits, the Black, Indigenous, and Latino/a to ghettos and prison cells, and left the Empire free to expand its wars for profit and shrink social services and civil liberties.

The sad reality is that the status quo, the day-to-day comfort, the conventional wisdom of empire is insanely anti-human. True human sanity does not consist of remaining calm, cool, collected—going on with life as usual – while the government murders Black activists, carpet-bombs Vietnam, trains torturers to ‘disappear’ trade union organizers in Latin America, and enforces the global economics of hunger on Africa.

Tweak a little here and there: add the list of 800 U.S. bases and a list of wars and proxy conflicts; add the documented names of the tortured and those rendered to other regimes for abuse; add the “disappeared” unions and union representations along with the disappeared jobs; and add the cities and towns of Kansas City, New York, Chicago, L.A, the reservations of Lakota lands, anywhere in the U.S., after Africa, as places where children suffer from Empire- induced hunger. Does this insanity/sanity scenario resonate with us today?

As Gilbert points out, yesterday’s movements (including the armed struggle led by WUO) drifted from a focus on solidarity with the struggles of people of color, in order to challenge imperialism and capitalism, to a focus on a “particular set of tactics.”

The killing of ruling class individuals or their armed enforcers, no matter how justified by the bloody war they waged on the oppressed,would be hard for those who hadn’t experienced the repression directly, even radical white youth, to accept. If our mass support evaporated, we wouldn’t be able to sustain armed struggles on any level.

Gilbert rightly rejects a romantic image of the Black struggle in the United States, but at the same time, Love and Struggle’s narrative unabashedly lays out what many of us have been writing for years now: the white support networks abandoned the struggles of people of color, without offering critical, useful,compassionate debate regarding the tactics of both the Black and white armed or unarmed struggles. This abandonment furthered the marginalization of the Black, Latino/a, and Indigenous struggles, and also led to the aims for fighting imperialist oppression to be viewed as “abstract” nonsense.

The prevailing wisdom in the United States is that good, law-abiding citizens will come to their senses when presented with the enemy in their midst. Consequently, police assaults against Black organizations and individual fighters continued. More and more Black fighters became prisoners of the State or corpses permanently buried underground. The “politics of creating an example and [a] presence of solidarity with people of color,” (an “essential step for developing any kind of revolutionary movement worthy of that name among white people”), was replaced with “self-serving motives.”

Activism promoting the organization’s leadership, Gilbert explains, and individuals pursuing “status within the organization,” became the work of WUO—when the bombs were not going off. As with most organizations of the ’60s and ’70s designed to fight imperialism, the hierarchal structure of WUO became “too top-down”; consequently, “the danger of being captured and the demands of armed actions put a premium on discipline and cohesion, while clandestinity and compartmentalization made open, organization-wide debate difficult.”

I could identify with David Gilbert as the observer of “rhetorical excesses accompanying a correct direction.” In a supportive position within the WUO, he had to contend with the chain-of-command, and, on the other hand, he was reluctant to express his “discomfort” and criticize decisions: “I didn’t want to be left out of the cadre who would be chosen to pursue armed struggle—to be, in the status consciousness of the day, revolutionaries ‘on the highest level.’”

Externally, the forces of power were in full swing, working to convert the non-activist, counter-culture generation into self-absorbed mutes, if not out and out capitalists.

As Love and Struggle argues, after the killings of four white youths at Kent State, white youth turned from forming solidarity with the struggles of people of color. It was too dangerous! The government would not hesitate now to kill white American youth! Youth were killed at Jackson State but they were Black!

White youths suddenly found themselves in the business of commune building and spirituality, (“the latter both in the progressive sense that we’re all one soul and in the more mystical way of looking to various supernatural forces for the answers to our problems”). Gilbert explains that the commune began as a “wonderful effort” to live cooperatively and in harmony with nature, but, by the mid-1972, the commune becomes more about “retreat – not just to the countryside but also from opposing the system.”

It is an old American story, and Love and Struggle does not avoid confronting and analyzing the announcement of its return in the heyday of the 60s/70s era. It co-opted the language of the youth movement, but it was the same American story: A “new consciousness” is sweeping the nation or a “new astrological age” is dawning! Live “in harmony with the spirits of nature or with the feminine goddesses.” In short, “achieve change without struggle”—without the people of color, particularly without the Black American!

Gilbert saw the unraveling of the movement coming while he was still engaged in his work with WUO. As he recalls, when the Left saw itself up against “a colossal and ruthless power,” it “retreated into a form of magical thinking: a recitation of Marxist dictums on revolutionary agency as a substitute for the concrete analysis of our actual conditions.” In the meantime, he writes, “the people we most admired, the BLA [Black Liberation Army], were now getting gunned down by the police and were on the run.”

Gilbert recalls the discussions that divided activists between those who blamed the movement’s crisis on too much theory and those who saw actions without theory, and the armed struggle in particular, as too defused and divisive. But Gilbert recognized that the problem was not theory per se, “but rather the deep history and powerful material impact of white supremacy and benefits from imperialism. He continues, “the repeated drifts into white opportunism also characterized movements that didn’t invoke M-L (Marxist-Lenin) at all, such as populism and women’s suffrage.”

Individual corruption breeds organizational corruption. For some, that corruption came in the form of drug addiction or in the pursuit of money or in fear of difference. For Gilbert, it was ego. Ego, he writes, lured him from the aims of liberation. The “‘exceptional white person’ mentality” does not engender solidarity with people of color and further “undermines any serious effort to organize other people against racism.” Similar to Mumia Abu Jamal behind bars, Assata Shakur in exile, and other political prisoners, David Gilbert continues to confront the forms of corruption that breed alienation rather than solidarity.

Whenever I start feeling full of myself or sense that I’m taking a direction that’s not right, I need to grapple with that and, if possible, get help. “How does or doesn’t this particular path advance the interests of the oppressed?” “What self-interest do I have here and how do they complement or conflict with the goals of the struggle?”

This book is an act of love. It is a timely gift to a new movement of young and old activist veterans. Love and Struggle is for you, if by now, 2012, you know which way the wind blows.

BlackCommentator.com

Editorial Board member, Lenore Jean Daniels, PhD, has a Doctorate in

Modern American Literature/Cultural Theory.