by Christine Wald-Hopkins

Tucson Weekly

February 16, 2012

This powerful novel, by a former investigative reporter, depicts the Southwest’s dark, soulless side

Smeared in my reviewer’s pencil scrawl cross the top of Page 110 of this new Barry Graham novel are the words: “I CAN’T FINISH THIS BOOK!”

I finished the book. And I skimmed it in a second read, all the while dreading Page 110.

It’s not as if you’re not warned. In addition to the cover blurb’s mentions of a “tragic sequence of events” and “explosive conclusion,” Graham’s narrator hints from the beginning that things might not turn out so well for the central character. It’s just that you come to like the character. Somehow, you feel that as a reader, your involvement in his life might queer the inevitable, or maybe the book might turn into a sort of grown-up Choose Your Own Adventure, or Meditate Your Own Ending. Graham is a Zen monk; can’t he arrange something?

But he can’t, and it didn’t. And I got to Page 110 again, and looked away again, and then realized that it’s probably not the story or even the character that this book is about—it’s not so much the what as the why.

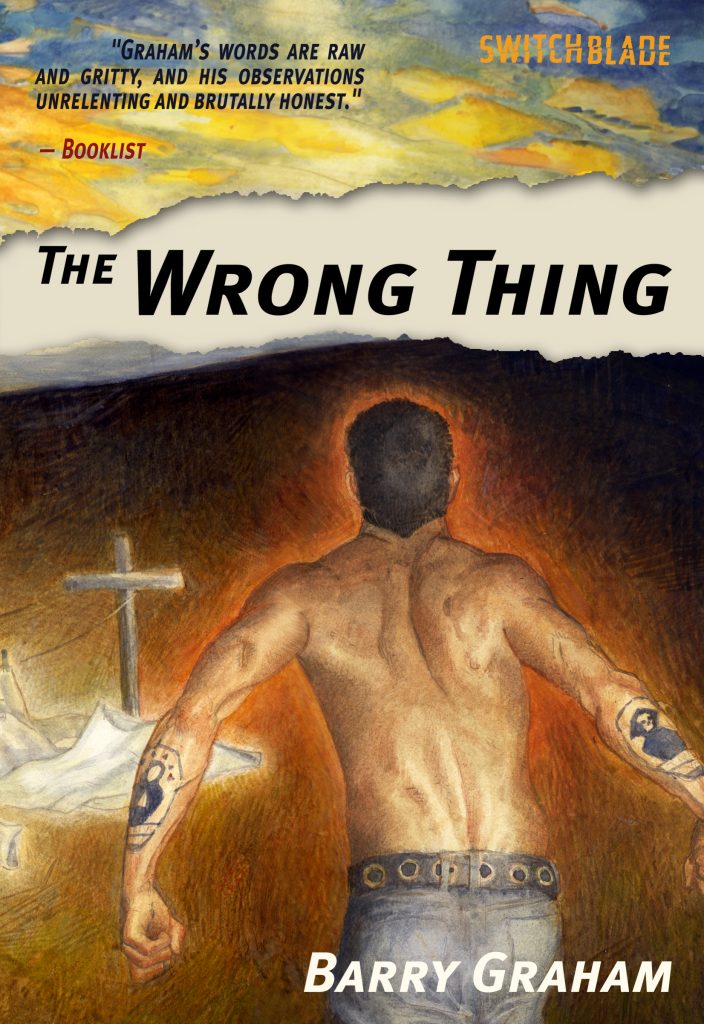

The Wrong Thing is about a slight, young Mexican American from Santa Fe known as the Kid. He’s introduced as if he were a legend, through rumors and sightings, and founded or unfounded allegations.

Unwanted by his family, not embraced by any adult, the Kid navigates childhood by scratching out his own paths: reading, learning to cook, defending himself with sharp objects, and getting into the drug trade. Never given affection, he doesn’t know how to express it. Neglected and ill-treated, he learns to meet physical abuse with stoicism and patiently nurtured revenge. By the time he’s out of school and jail, he can murder without compunction.

It’s when he begins to take responsibility for others—a pleurisy-afflicted beauty who works at Woolworth’s, and a stray cat—that the Kid experiences some modicum of joy. Too bad his die has already been cast. Thank Graham that he gets a moment of awareness and grace.

So, why, The Wrong Thing?

According to the press release, after Graham’s four novels about the “urban wasteland” of his native Scotland were little noticed at home, but recognized in the U.S. (the American Library Association named The Book of Man one of the best books of 1995), he packed up and moved to Phoenix to write about our urban wasteland.

He highlights the economic disparities and social blights of the Southwest: Santa Fe’s moneyed, gentrified society contrasts starkly with the Kid’s family’s poverty. The lack of social services and economic opportunity contribute to how the Kid’s life plays out.

One-time boxer and investigative reporter Graham also takes on other aspects of the region—which comes across as a desert more than just geographically. The Kid spends some time in Arizona, where it’s so hot that “everything seem(s) to be on fire,” and Phoenix feels “like science-fiction movies, like maybe Blade Runner. The streets were jammed with cars, but there were no people on the sidewalks, nobody walking anywhere. There were no individual stores or cafes or bars on the streets, only strip malls.” Graham takes a few jabs at Arizona’s law enforcement, politics and newspapers, too.

The question of why the Kid acts as he does remains, and some of Graham’s other writings might answer that. As a reporter, Graham witnessed two executions. In Why I Watch People Die, he muses about the 1998 execution of 43-year-old Jose Jesus Ceja, who committed a double-murder when he was 18. Even the original judge pleaded for his life at a clemency hearing, but they executed him anyway. “Welcome,” Graham writes, “to Arizona.”

In the same passage, Graham writes about himself. In 1984, when he was 18, he actually planned to kill and rob a man. Broke and hungry, Graham armed himself with a screwdriver with a weighted handle and went into a bookstore intending to “smash the (elderly owner’s) head and pocket the money.” After loitering and waiting for a customer to leave, he approached the owner intending to assault him. He was thrown off, however, when the old man merely bade him farewell.

“I walked down to the river and dropped the screwdriver into the water.”

Graham must have had something going for him that the Kid doesn’t.

As Graham presents it, immaturity, desperation and flat-out fear can drive someone to do the unthinkable—and no amount of magical reader thinking can undo the effects of a soulless, violent society.