By Scott Adlerberg

Literary Hub

December 7th, 2017

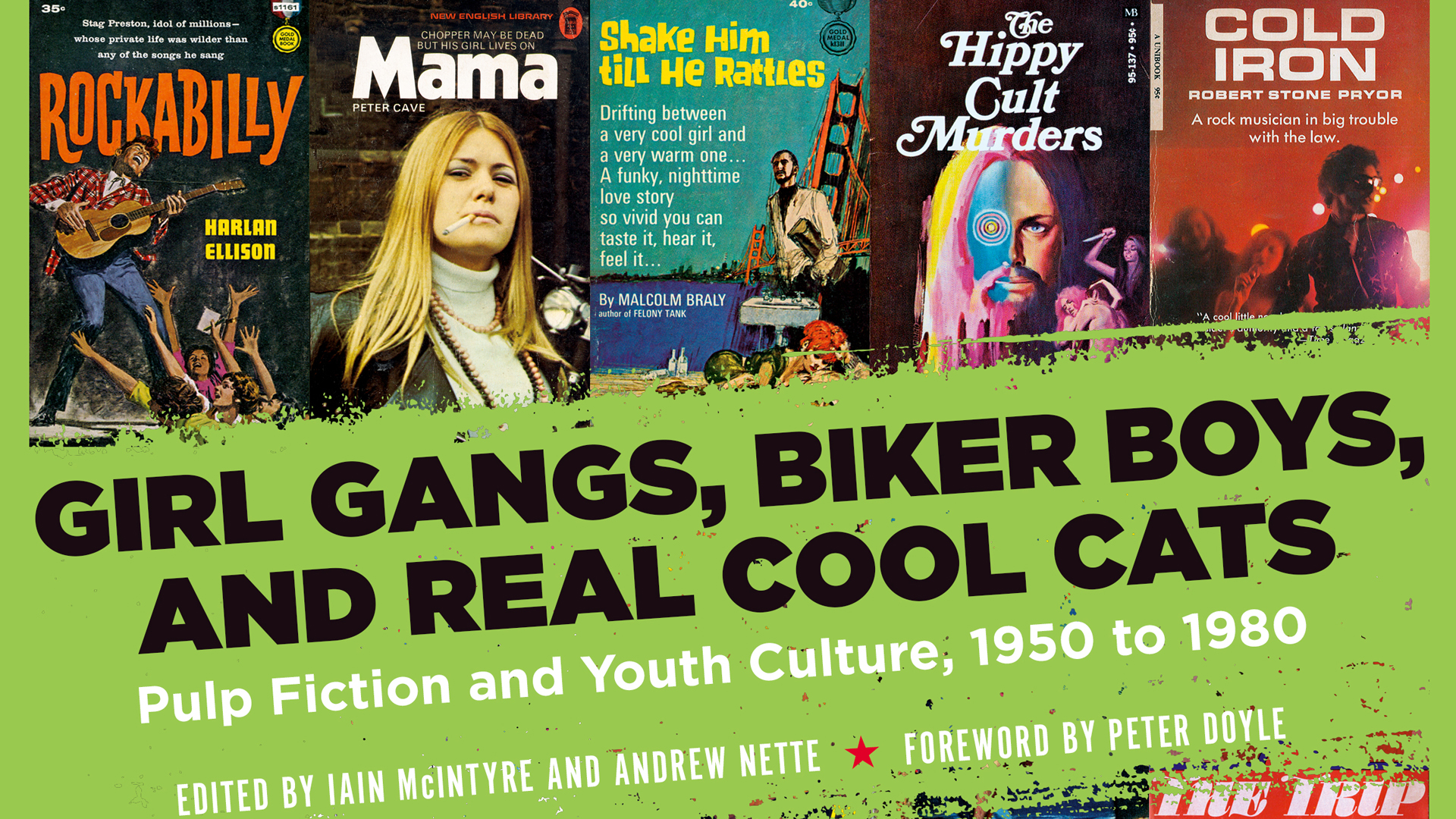

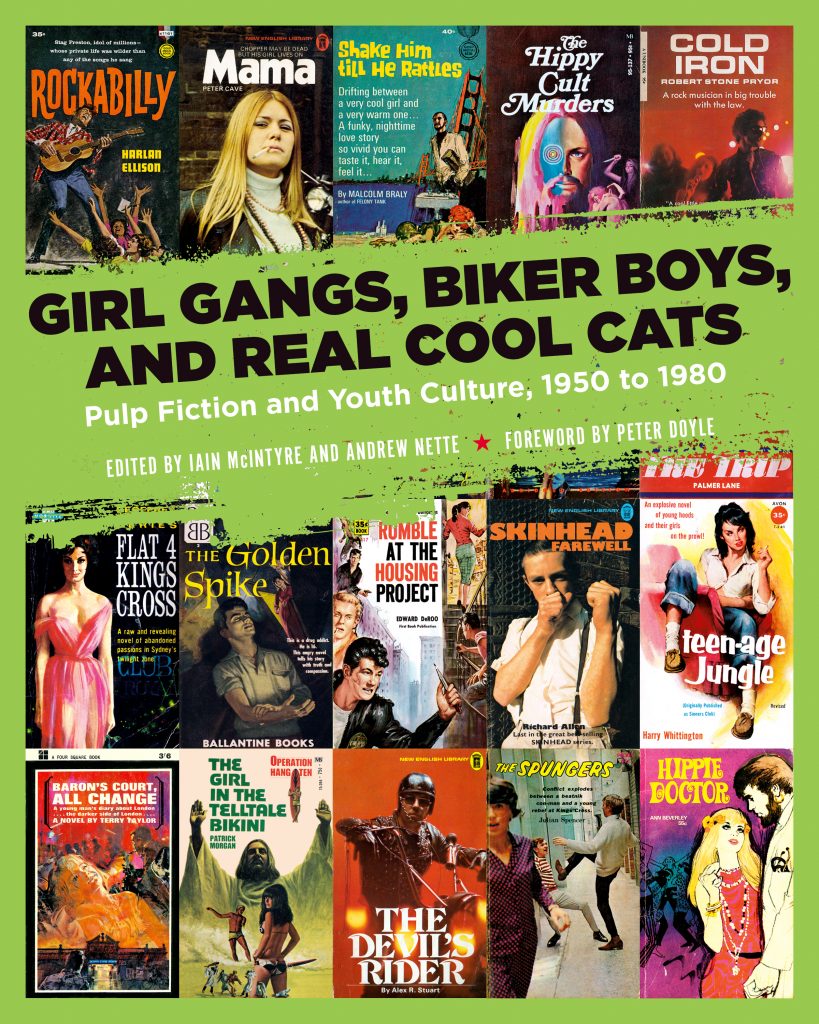

It

takes scholarly love and a fan’s enthusiasm to devote oneself to

putting together a 300-plus page book dissecting obscure pulp fiction.

But that is exactly what Australian writers Andrew Nette and Ian

McIntyre have done with Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980.

Their ambitious work “chronicles three decades of public anxiety, fear

and fascination in the United States, Britain and Australia around the

concept of out-of-control youth, and the rapacious genius of pulp

publishers in exploiting it to sell books.” They serve as co-editors for

the volume, which is filled with essays about out-of-print novels few

people remember. The contributors’ voices vary in tone—analytical,

humorous, elegiac for publishing trends that have passed—but all the

voices are accessible. That Nette and McIntyre have produced a book that

is not esoteric serves as a testament to their clarity of purpose. Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats

is a book they want a broad audience to enjoy. They want readers to

partake of the pleasures they’ve derived from pulp’s sense of the outre. For each of them, this pleasure has been deep and sustained, back to when, years ago, they first discovered pulp.

In Nette’s case, as he says, his father was a big pulp fiction reader, and he remembers seeing the books on the shelves in his father’s den. Although he didn’t read the novels until much later, he can recall how the cover art and racy titles fascinated him. To his young mind, these things provided a keyhole glimpse into what seemed a dangerous and exotic world. In particular, his father loved Carter Brown, the pseudonym for a Sydney author named Alan Yates.

Nette remembers a black and white photograph he used to have—a photo of his dad in the late 1960s sitting on a beach chair on vacation, wearing dark sunglasses and reading a Carter Brown book called Kiss and Kill. It was a paperback, of course. Brown’s work, like a lot of Australian post-war pulp, was total faux Americana, mainly private eye stories set in American cities such as New York or Chicago. But they sold remarkably well—worldwide, in fact, translated into numerous languages—and when Nette himself started reading about Brown, he was astonished to find that an author so successful was little known in Australia’s mainstream literary circles. He would come to understand, as he puts it, “that the Carter Brown books, like most pulp fiction, were largely dismissed because critics did not view them as serious literature.”Article continues after advertisement

The Carter Brown phenomenon got Nette interested in pulp more generally. It alerted him to the variety of pulp sub-genres and the myriad authors churning the material out. And since that initial spark of curiosity, through adulthood, Nette has become what can no doubt be called a pulp connoisseur. Besides writing two crime novels, Ghost Money (2013) and Gunshine State (2016), the first set in Cambodia and the second in Australia and Thailand, he runs a longstanding blog called Pulp Curry, which features pieces on all manner of things pulp related—in fiction, film, television, music, and culture in general. Right now, he’s immersed in his Ph.D dissertation on the history of Australian pulp fiction. Put Andrew Nette in any used bookstore, and he’ll waste no time inquiring whether there’s a section containing old pulp paperbacks. If there is, he makes a beeline for it. He’s always in pursuit of a discovery, the gem gathering dust that he can pluck off the shelf and add to his collection.

Despite his many projects over the years, Nette had also been looking to get a book-length study about pulp fiction off the ground. Because of the field’s enormity, he was hoping to find a person to collaborate with. He happened to meet Ian McIntyre at the 2012 launch of McIntyre’s Sticking It to the Man, a brief history of countercultural pulp covering the years 1964 through 1975, and the two hit it off. Through their discussions, Nette learned that McIntyre shared his wish to do a comprehensive volume on pulp fiction. The question remained, though: how to approach the subject’s vastness? They kicked ideas around for a while. Only when they decided to focus on how pulp fiction has portrayed post-war youth culture did they find the thread the book needed that allowed them to proceed.

For McIntyre, the interest in youth subcultures developed when he was a teen in Western Australia during the mid-1980s. Punk culture made an impact on him, especially the idea that if you love something you should be able to contribute to it. His first exposure to pulp came around the same time, when he started reading Richard Allen, one of the pseudonyms used by UK-based writer James Moffat. Moffat produced hundreds of novels through the 1960s and 1970s, and as Allen, his output exploited British subcultures like the skinheads. In secondhand bookstores all over Australia, his books were widely available, and McIntyre tore through them. He soon became a fan of crime fiction and sci-fi. Outside his reading, through his late teens and twenties, he played in bands, did radio shows, and took part in political activism. He went from writing and distributing fanzines to writing books on Australian garage music, the country’s 1960s psychedelic scene, and various radical political movements.

It’s important to note that Nette has long been politically active, too. He is a committed progressive, and for much of his adult life, has supported himself as a journalist or through policy writing jobs. Both he and McIntyre regard pulp as something besides just entertainment; it’s a mode of fiction rich with socio-political meaning. As Nette says, he is interested in pulp fiction’s role “as a vast cultural consciousness. Deposited there were fantasies of fulfillment as well as desperate yearnings, petty betrayals, unrequited passions, and unreasoning violence that troubled the margins of the longed-for world.” (He is quoting Susan Stryker’s 2001 book, Queer Pulp, here.)

A challenge Nette and McIntyre faced was finding contributors who could deliver the type of pieces they, as editors, envisioned. It was essential the writers read and analyze the books they were describing rather than merely talk about the outlandish covers or make generalizations about the extravagant nature of pulp. In addition, the project demanded they find people who could write the right way about the novels. Nette points out the hardest aspect of writing about pulp: while you often have to deal with how badly written, outrageously plotted, and politically incorrect the books are, you still need to discuss how they represent an alternative historical awareness. Approach the books too reverentially, and you sound silly or as if you are praising their worst aspects. Tackle them purely from a 2017 perspective, and the writing will feel detached and superior, missing their cultural connections and significance. Both editors think that the Girl Gangs contributors struck the balance the essays needed, whether talking about authors now forgotten or authors who, after their pulp beginnings, made lasting literary names for themselves—people such as Harlan Ellison, Colin Wilson, Lawrence Block, and Marijane Meaker (aka Vin Packer and M.E. Kerr).

Post-WWII youth culture in Britain, the US and Australia created new styles of music and fashion. As mores shifted and the young became increasingly rebellious toward authority figures, pulp fiction chronicled these changes, hyping and exaggerating them for mass consumption and cheap thrills. What Nette and McIntyre value is how pulp writers took advantage of these developments, slabs of everyday experience, and put their stories on the page fast. To them, pulp had an immediacy, perhaps even an intimacy, that a great deal of post-war literary fiction lacked. In Nette’s words: “The pulp novels examined in our book serve as an example of the way pulp often held up a mirror to mainstream society. They reveal as much about post-war society’s hidden and not so hidden desires and fears as they do about the sub-cultures themselves.”

Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats is the first of two pulp history books Andrew Nette and Ian McIntyre have co-edited. The second volume will come out in late 2018 and looks at radical and counter-cultural pulp fiction. The countries studied will be the same, the time span the late 1950s to the early 1980s, but there will be a fresh group of contributors, reflecting the different subject matter. This time the concentration will be on books about Black Power, the anti-Vietnam War movement, gay liberation, and science fiction. Nette and McIntyre promise another collection of insightful pieces, where the serious and the ridiculous, the earnest and the lurid, are considered with equal weight.

Scott Adlerberg lives in Brooklyn. His first book was the Martinique-set crime novel Spiders and Flies (2012). Next came the noir/fantasy novella Jungle Horses (2014). His short fiction has appeared in various places including Thuglit, All Due Respect, and Spinetingler Magazine. Each summer, he hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series in Manhattan. His new novel, Graveyard Love, a psychological thriller, is out now from Broken River Books.

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page