by Kristian Williams

In These Times

March 5th, 2013

A new volume revisits the series that breathed new life into the genre

In the late 1970s, mainstream comics were a dull affair, dominated by superheroes and still bound to the politically conservative and culturally puritanical guidelines of the Comics Code Authority.

Maus, Watchmen, and The Dark Knight Returns—along with the broader recognition that comics “aren’t just for kids anymore”—were still almost a decade away. The Underground Comix scene, like the hippie counterculture with which it was associated, had peaked a few years earlier and badly needed a new direction. Then, in 1978, came the first issue of Anarchy Comics. Thank god for punk rock.

Anarchy Comics, which appeared four times between 1978 and 1987, published by a collective in San Francisco, represented a unique collision of Underground Comix sensibility, punk aesthetics and utopian politics. On its pages, radical history, autobiography, poetry, satire, cultural criticism and gag cartoons gathered together promiscuously. Art and pulp, fiction and nonfiction, idealism and cynicism didn’t merely appear alongside one another but often intermingled, and even blended together. The result was cacophonous, more chaos than order, closer to the antics of the Sex Pistols than the philosophical reflections of Kropotkin.

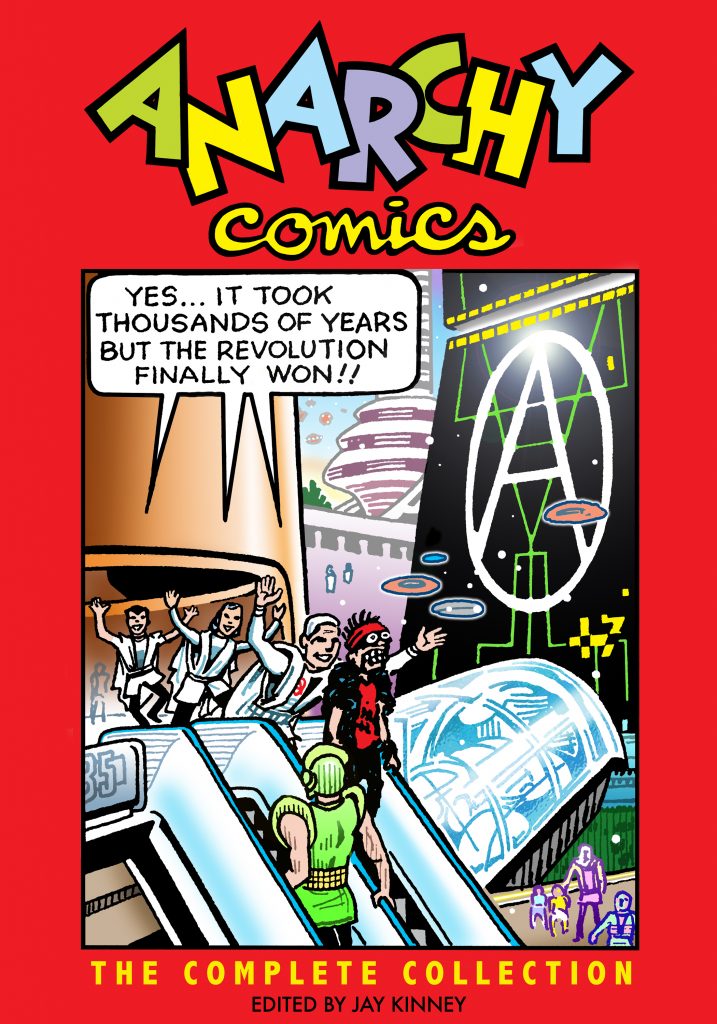

Now, PM Press has collected all four issues into a single volume. In addition to reproducing the content of the original comics, Anarchy Comics: The Complete Collection also includes color reprints of the covers, unpublished sketches, archival photos, a long introduction from editor/contributor (and former In These Times cartoonist) Jay Kinney, a short preface from historian and comics scholar Paul Buhle, and a recent story by one of the original contributors, Sharon Rudahl.

Anarchy Comics was in many ways an obvious product of its time. The Cold War, the possibility of nuclear annihilation, the ascendancy of neoliberalism, and the Left’s increasingly sectarian and politically-correct self-isolation, all form part of the background of the publication. Aesthetically, as well, Anarchy Comics reflects the moment of its birth. The irreverent playfulness of the Underground Comix era carries over into many of the pieces here, but they also incorporate a punk aesthetic (or anti-aesthetic) and thus feel hastily, or almost indifferently, slapped together. Some of the pieces make ready use of clip art; some pages are almost illegibly crowded with images or text; much of the art is aggressively crude; and several stories halt abruptly, without resolution, at the end of the page. As a result, much of the work seems unfinished, fragmented or abandoned, though this effect sometimes also provides a daring, experimental, spontaneous feel—like a flash of pure creative energy, brilliant for a moment but impossible to sustain.

The best qualities of the volume are represented by the contents of the second issue, which included an autobiographical tale in which Steve Stiles is interrogated by Army Intelligence about IWW activity; a punk-inspired Archie parody titled “Anarchie in Problem Child”; and lush, grotesque, erotic images paired with quotes from Emma Goldman. Some of the art, such as Clifford Harper’s cubism-inspired illustrations for Brecht’s poem “The Black Freighter,” is so striking that the word “cartoon” will not even come to mind.

Perhaps the most interesting element of Anarchy Comics is its roster of contributors. Featuring talent from throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe, the comic ranged freely across subjects, styles and outlooks. Altogether, the collection includes more than 65 separate stories from 30 cartoonists who as a group represent both the past and the (then-)future of anarchist cartooning.

Contributions from figures from the Underground Comix era—like Gilbert Shelton, the creator of the “Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers,” Greg Irons and Peter Pontiac—give the book a sense of lineage, and help to position it at a pivot between two counter-cultures—the bleary hippy scene before, punk aggression after.

Fascinating too are the contributions from artists who had yet to reach their prime. Sharon Rudahl, who began in the 1970s Underground scene, went on in 2007 to publish a book-length comic biography of Emma Goldman called A Dangerous Woman. Her growth as an artist is on display in this volume as well, with a lovely short bio of Victoria Woodhull (from 2010) contrasting markedly with the competent but uninspired historical pieces from the first couple of issues. Meanwhile, “Quotes from Red Emma,” along with a firsthand account of facing censorship, illustrations accompanying a pair of Benjamin Peret poems, and the feminist fable “The Quilting Bee,” are all the work of Melinda Gebbie, who would later become notorious as the co-creator (with Alan Moore) of the self-consciously pornographic three-volume comic Lost Girls. Her Anarchy Comics contributions, while less constrained and less refined, are clearly the work of the same artist, and these early pieces—especially with their themes of free love, free speech and feminism—provide another point of comparison for her later, better known work.

Clifford Harper—who would become famous for his bold, dark, woodcut-like images, his anarchist portraits, and for Anarchy: A Graphic Guide—contributes a piece to every issue collected here, each in a startlingly different style. The illustrations for “Owd Nancy’s Petticoat,” in the first issue, resemble early nineteenth-century woodcuts; the Brecht illustrations in the second issue are nearly cubist; the ones accompanying Proudhon’s “What is Government?” in issue three are softer, with rounded edges and gray shading; and by the last issue, his illustrations for “On the Night of March 3, 1982” finally achieve his characteristic high-contrast, block-print style. To encounter these decades-old works, knowing the artist that he would eventually become, is interesting, and even revealing.

Of course, alongside these works are other contributions which seem, at least in retrospect, silly, pointless, crude, or—perhaps worst of all—dull. It’s tempting to wish that the volume had been edited differently, offering the best works from the original issues and discarding the weak, unfinished or dated. But in fact Kinney has done us a favor in offering a facsimile edition. The raw, confused feel of the work included here—along with its uneven quality, and the occasional obvious failure—offers an honest picture of culture as it is created, and of politics as it is practiced. Neither masterpieces nor revolutions arrive fully formed. They arise, instead, haphazardly, from messy social circumstances, caught within the tensions of their time. To cut out everything embarrassing or regrettable would be to misrepresent the past, to lead us toward nostalgia rather than history.

Such an approach would also misunderstand the virtues of Anarchy Comics as a project. Considered in its context—born in the midst of the punk era, after the disintegration of the New Left, before “graphic novels” gained respectability—the effort seems bold, audacious, even foolhardy. The crass, awkward, ugly, amateurish elements are all a part of that. They remind us that success and failure are often twins—arriving in the same moment, emerging from the same process—and that continuous failure is sometimes a necessary accompaniment to the maturing of success.

Anarchism may be utopian, but, as Anarchy Comics reminds us, it has never been perfectionist.