by Courtney McSwain

emPower

November 14th, 2012

If you’ve spent any time in Washington, D.C.’s Busboys and Poets, the popular restaurant and community gathering space located on the city’s busy U-Street corridor, then you’ve probably come across Derrick Weston Brown. A poet, book buyer, teacher and author, Brown was responsible for developing the restaurant’s poetry programming under his early title as poet-in-residence. No longer under that title, Brown continues to take his role as poetry convener to heart.

His poem, “The Mic is Now Open,” serves as his monthly clarion call for poets of all designs to step to the mic during the “Nine on the Ninth” open mic poetry series that Brown hosts at Busboys and Poets. Perhaps more important than his time on stage is his role at the independent bookstore located inside the restaurant. Operated by the nonprofit organization Teaching for Change, the bookstore offers an in-depth collection of progressive poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and children’s literature, which Brown curates as the store’s publication advocate.

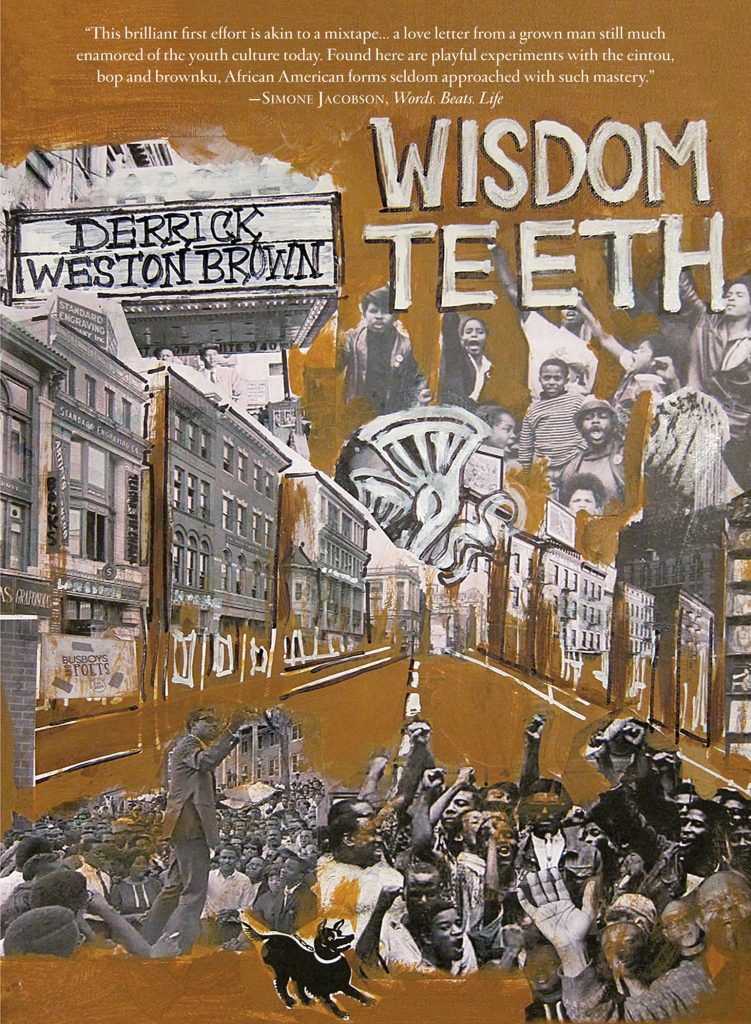

Recently, Brown added author to his resume, with the release of his first published poetry collection Wisdom Teeth,

on Busboys and Poets Press, an imprint of PM Press, last year. His

collection, which Brown describes as an exploration of change and

growth, covers issues of race, masculinity and relationships in

unexpected, sometimes harrowing ways. At its most intense, Wisdom Teeth

displays Brown’s ability to place himself within the most difficult of

emotional circumstances in order to reflect the voice of those

characters whom he tries to understand. Those who know Brown best

describes him as an observer and witness bearer.

“He and I like to go

people watching and look at how people are interacting,” said Alan

King, poet and close friend to Brown. “One of the things I admire about

Derrick is his ability to make the audience feel whatever moment he is

writing about.” .

While capable of taking on sobering topics in

his work, Brown is more of an upbeat poet than a suffering one. “He’s

very affable, down to earth, humorous,” said Dr. Tony Medina, a Howard

University creative writing professor and one of Brown’s mentors.

Perhaps

it was his affability that allowed him to indulge nearly two hours of

my questions on a recent Saturday morning when I spoke with Brown about

his curiosity, influences, humor and hopes of becoming the next public

television icon.

CM: How did you come to poetry?

DWB: I have an aunt who was a librarian, so there were times when my mom would have to work during weekends and I would go to work with my aunt. I would be there for up to eight hours, and there was a little back room

a portable record player and read along vinyl records. I would sit down and read along with all sorts of stories from around the world. That shifted into my love of theater. Poetry just kind of found me as a part of the things that I enjoyed. It involved a lot of imagination, and wherever theater was there was music. Wherever music was there was poetry.

The key thing is, [for] my first poetry book, my dad gave me this book called “My Daddy is a Cool Dude.” It was written in maybe the mid-70s during the Black Arts Movement. The poems are very centered around black families and black people. The two poets and illustrators are from Chicago, a hot bed for the Black Arts Movement. Those poems were really short and neat, and I [have] always kept the book with me.

CM: Do you remember your first moment of writing?

DWB: I was probably in the fifth or sixth grade and I would write little poems. Some of them rhymed, some of them were stories. My mom took the poems one day and she made this little book called “Derrick’s First Works.” She printed and laminated them and gave it out to family members during one of the holidays. She’ll tell you, ‘I was Derrick’s first publisher.’

CM: When did you start taking it seriously?

DWB: College. I went to Hampton [University] in 94-98. There was this organization called the Men’s Association, and we used to have this set called “Culture Create.” MCs would get together and rhyme freestyle and people would do poems. You got to see the mixture of styles and songs and an interesting intersection of people. Everyone was coming for something, and it was just so exciting to hear people share different things. I graduated in ’98, and I ended up doing freelance writing for the Charlotte Post, a black newspaper, and I got to cover stories about the rising performance poetry scene there.

And we’re not even going to talk about when [the movie] Love Jones came out—it was a wrap for a lot of people. All the people that didn’t like poetry but loved that movie were like, ‘You mean you could pull women or you could connect and be all fly and it’s okay to be smart? I think I might have a future in this.’

That wasn’t me, I was just saying.

CM: I’m glad you brought this up. What do you make of the whole Love Jones, Darius Lovehall poetry emcee thing?

DWB: I think people saw Love Jones—it’s such an endearing movie—and were like, ‘I want a part of that.’ So, it was a good thing because it brought more people to open mics. But at the same time, you had people that came in looking for that feeling but weren’t necessarily trying to do the work. Some people came out for the aesthetic, of course. Some people left it after they got what they wanted, and others stayed and continued on with the craft.

CM: What inspires you to write?

DWB: I like to watch people. Sometimes it’s writing just to report what I’ve observed. To document things, like change. As I get older, I realize that writing is something personal for me too—it is therapy. If I haven’t written regularly in a while, I get apprehensive. It’s very—it’s almost like I’m afraid to start writing because I’ll have all these expectations. I just have to bring myself back to—just write something down, feel better.

CM: When you said you like to watch people, I was reminded of what Ruth Forman said in the trailer for your book about you being a great witness. Is that where some of that comes from?

DWB: Yeah, it’s interesting. You know how babies stare and their parents tell them don’t stare? But with babies, it’s almost like [they are saying], ‘I want to see. I’ve never seen this before. What is that?’ As you get older, we’re socialized not to stare, not to look too deep into things. Sometimes you see some stuff that is just so interesting, or you overhear. I call it eaves dropping but my students call it ear hustling.

CM: Who are your poetic influences?

DWB: Paul Beatty probably at the beginning. Saul Williams. Sonia Sanchez, because she talks about how she found herself in haikus, and I like haikus. Also I had the biggest crush on her. I don’t think I get too star struck, but I remember I was at the Furious Flower Poetry Conference in 2004, and I saw her and wanted to go over and talk to her but I was so freaking shy—I couldn’t do it. The poet Kelly Norman Ellis went over there [and said], “Hey Professor Sanchez, this is Derrick Brown.” I told her, “Professor Sanchez, I really love your work. I feel like I was born too late. If I had been born at the same time [as you] we could’ve been together.” She was probably thinking, ‘Little boy I’d tear you up.’

So

Sonia Sanchez. When I got in grad school that’s when I really, really

started reading other writers. I had a professor, Myra Sklarew. She was

really helpful about pushing me to work. We would have our workshops and

she would say you can go further with that. Lucille Clifton. Dr. Tony

Medina used to always talk about the economy of words, and she [Clifton]

can give you a whole world in 10 lines. Sekou Sundiata, who was more

performance, he wrote plays.

Not just poets, Shel Silverstein. I’m a

big fan of comic books. My favorite graphic novel, I’m not ashamed to

say it, is about a samurai rabbit.

CM: A samurai rabbit?

DWB: His name is Usagi Yojimbo. Usagi means rabbit in Japanese and Yojimbo means bodyguard. I am not ashamed.

CM: Where does your humor come from?

DWB: Storytelling. I like humor. I like laughing. I still think one day maybe I would try stand-up. I love improv. The humor comes from the comedians that I like also. Richard Pryor, Robin Williams and, you know he’s not really a comedian but, I’m going to list Wayne Brady. Wayne Brady is a brilliant dude. He showed his range on that episode of Chapelle Show. Whoopi Goldberg is awesome at improv. Carol Burnett. Funny people.

CM: Did you get all of that as a kid watching TV or listening to records?

DWB: I watched a lot of TV, but my mom monitored it. I watched a lot of public television. I watched Reading Rainbow. When Reading Rainbow was canceled three years ago I was hurt because, really, I wanted Lavar Burton’s job. My goal was—he was going to retire, and they would look for a new host, and I was going to be like, ‘holla’ at your boy.’

CM: What does it feel like when you’re writing?

DWB: Sometimes it’s an exciting feeling. A word may come, or a phrase or a voice, and I’ll write it down and see how far it goes. If it starts to fade, I try to push it to where it comes back. Or sometimes it’s a thought and I go and do some research.

Then, sometimes—like at my best friend’s wedding—I wrote a poem for the wedding and I’d been thinking about it and thinking about it. On the wedding day, we’re about to go down probably in about 40 minutes. So I’m sitting in the room with Alan [the groom], his dad, his brother, best friends, the bride’s brothers, everyone. This little line came up, “It’s not math.

It’s not statistics. It’s not…” I sat there with my notebook and I wrote it out. They were like,

‘Derrick what are you doing?’

‘Writing the poem.’

‘Oh, okay.’

Alan laughed because he knows there are times I can do that. But I hate it—why put yourself through that? Sometimes that’s what gets it out of me. I put my feet to the fire and there it is.

CM: What’s the longest a poem sat with you, from the idea to what you may consider completion?

DWB: One of the “Sweet Home Men” series poems, “Halle Tells How They Broke Him.”

[Brown

writes a series of persona poems in the voice of the “Sweet Home Men”

characters from Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved, which was set on a slave

plantation. In “Halle Tells How They Broke Him” Brown takes on the voice

of the male character Halle, who witnesses his love Sethe being beaten

and raped by white men before their planned escape.]

That one stuck

with me for a while. I always go back to that series because it’s not

done. I have to go to a place that’s kind of dark, and I have to be in a

certain mood to go there. If I’m in a bad mood, I ain’t going there. I

kind of have to be pretty good, feeling good, before I go there.

I have to think about…to live in a time when you’re enslaved and you know that you’re with someone that you love. It wasn’t someone that was chosen for you to breed or make children that are going to be sold. In that story, Sethe picks Halle. At that time you didn’t have control over who you wanted to love. I thought about the images and I saw the woman that I love, mother of my children, getting whipped and beaten and molested. What does that do to a person?

In the book it drove him [Halle] mad. I had to go to that place, and I didn’t like going there. But I had to write it in the sense of, ‘what if you lost it all?’

CM: Why did you decide to put yourself in that personal place?

DWB: I really love Beloved. But I left the book feeling like I really wanted to know more. So the only way I figured I could do a persona poem and really push the story even further, beyond what Toni Morrison was talking about, was to kind of put myself in it.

CM: In the forward to your book, Simone Jacobson writes, ‘Wisdom Teeth offers a collective biography of the complexity of black male existence in America…Wisdom Teeth indicates the stubborn release of the past, the things we choose to let go and the things that make our men ache with pain.’

What do you see, or what are you feeling that black men are aching from right now?

DWB: How much time you got? I think there are things that black men ache from that are specific, but I also think there are so many other people connected to that because I think that a lot of pain is shared. Still, men aren’t supposed to acknowledge pain or show vulnerability. If there is an expression of it, it comes out in presumed ways, or sometimes I say pr-eapproved, ways—blow something up or beat somebody up. I’ve never liked that outlook. I think you have to have another outlet. There are some things that hurt that you can’t express through your screaming and breaking stuff. Sometimes people really need to talk to somebody—just need to let somebody know, ‘I’m actually scared’ or ‘I’m actually dealing with this.’

CM: That reminds me of the line in “Halle Tells How They Broke Him” where you write, “But where did they learn how to break us in places they can’t see.”

DWB: Because you’ve got the physical violence of slavery, but then there’s the psychological, emotional stuff. When you don’t regard somebody as human, you can do whatever you want because they’re not human beings.

CM: Did you set out to have a particular statement with Wisdom Teeth?

DWB: One thing they talk about in workshops is when you’re putting together a manuscript you try to see how the poems can speak to each other. As I was putting the manuscript together, I thought about what speaks to what. That was the hardest part. It’s funny because my graduate school MFA thesis was called Wisdom Teeth, but then that manuscript changed [and] I gave it another name—Woodshed. That didn’t work, so I gave it another name—Watershed. It had different names, but then it came back at the very end, full circle, to Wisdom Teeth.

It’s a metaphor for growth and pain and removal—or inevitable removal, inevitable growth—in life. That’s kind of how Wisdom Teeth are.

CM: What advice would you give someone who wants to make poetry his or her life?

DWB:

Read. Read. Read. Read everything. Don’t just read poetry. Also, read

other poets outside of your ethnicity, outside of your culture. If you

hear other poets telling you about someone, go find out. I do think

there is something to be said for listening. Also, involve yourself in

other art. There are times when I don’t feel like writing poetry all the

time, that’s when I do prose and I’ve done some collaging. If you can

work within your art and make a living, that’s great. I’ve been a

librarian, I’ve worked at a newspaper and I’ve worked in several

bookstores and music stores—things I love to do but are still within my

art.

CM: Who’s the coolest person you know?

DWB: Alan King.

Not just because he’s my best friend. But I love the fact that that cat

has a photographic memory. I can remember certain things, but he can

remember conversations and stories to the tee. He’s the closest thing I

have to a brother. We’re on similar paths and still two different

people, so watching his growth as a poet and as my friend is always

interesting. He’s just a cool dude. The main thing is, because he can

change the breaks on his car. I am not anywhere close to being

mechanically inclined. His father is a master electrician, so he knows

how to do that too, and I just think that’s fascinating.

My

girlfriend is cool because she can take stuff that people throw away and

make amazing things. She made some shorts out of old jeans that I had.

She cut them up, got a little cargo belt, and they looked great. No

sewing or anything.

CM: That is pretty cool. I wish I could do that. What’s the dream for Derrick Weston Brown?

DWB: The dream for Derrick Weston Brown is that maybe at the end of my life I’m just as enthralled with the world and enthusiastic about life and people and the human experience as I was when I was four or five years old. I don’t want to leave this world bitter. I want to leave it with some hope. Not just for me, but maybe the work that I do gives the world hope.