by Duncan Campbell

The Guardian UK

June 3rd, 2014

In

1972 John Barker was one of four Angry Brigade members sentenced to 10

years in prison for a series of bombings. And although his newly

published novel is a crime story rather than a political tract, there’s

still plenty to feel outraged about

‘These are horrible times’ … John Barker. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Just over 40 years ago, John Barker appeared in the dock at the Old Bailey charged, as a member of the Angry Brigade, with conspiracy to cause explosions. He was jailed for 10 years at the end of what was then Britain’s longest trial. Now he has written a novel, Futures, a tale about crime, the financial markets and cocaine dealing, set in 1987 amid the first signs of the City mayhem that would bring such chaos in its wake.

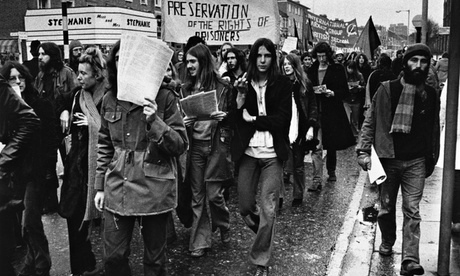

The Angry Brigade carried out a series of bomb attacks in the early 70s, aimed at the embassies of far-right regimes, the homes of cabinet ministers in Edward Heath’s Conservative government, the army, the police, property speculators, the Miss World competition. Each attack was followed by a communique written on a John Bull printing set in which the motivation was explained, whether it was internment in Northern Ireland, the Vietnam war, the government’s industrial-relations policies or sexism.

The explosions led to the formation of the bomb squad – now the anti-terrorist branch – and the eventual arrest of a dozen leftwing activists, of whom Barker, then aged 23, was one. He stood trial in 1972 with seven others: the Stoke Newington Eight, as they were called, because of the location of their flat.

Four of the defendants were acquitted but Barker, along with Hilary Creek, Anna Mendelssohn and Jim Greenfield, were convicted on majority verdicts. While some of the evidence against them was dubious, Barker acknowledges that “they framed a guilty man”. The jury asked the judge for leniency and Mr Justice James, having told the defendants that they suffered from “a warped understanding of sociology”, duly gave them 10 years rather than a possible 15.

Barker defended himself in the trial. “At least one person in a political trial should always do so,” he says when we meet in his small flat, not far from where he was arrested all those years ago.

Some of the lawyers in court said he could have made a successful barrister and the Observer likened his closing speech to that of “a Non-Conformist minister trying to put over the Message”.

Futures was written more than 20 years ago and its publication by the radical imprint PM Press later this month (via Kickstarter) follows earlier editions in France and Germany. It tells the story of Carol, a young single mother and drug dealer, Gordon, a “tasty”, self-regarding old-school London gangster, and two coke-snorting financial analysts, Phil and Jack, who entertain a fantasy of a cocaine futures market. Their internal lives are described in a richly original, cliche-free style and the book is remarkably prescient. “It’s a kind of crime novel – in no way a political tract,” says Barker. “Will Carol or won’t she do this one big deal that will get her out of the drug world? I feel very sympathetic to her – she is representative of a very ordinary person who has to make this decision. I wanted the gangster character to be totally unromanticised – nasty but boring.”

The son of a sub-editor on the sports desk of the Evening Standard, Barker grew up in Willesden, north-west London, and was attending CND demonstrations at the age of 15. He read English at Clare College, Cambridge, where he met Greenfield, later a co-defendant. In what was called the Campaign Against Assessment, he and a group of like-minded students tore up their final exam papers. “We went to the front of the exam room and said ‘Down with elitism’, or something like that. The university was very annoyed. It was quite a sustained campaign – we did it because the British education system is basically one of exclusion, repressing any kind of critical thinking for most people.”

An Angry Brigade march in north-west London in 1972. Photograph: Hulton Archive

Initially, he made a living with a weekend book stall in Petticoat Lane market in east London, and building work. His increasing involvement with politics, in Notting Hill via the Claimants’ Union – which campaigned to get people the benefits to which they were entitled – and other groups led him eventually into the world of the Angry Brigade. Their aim was to damage property rather than people and no one was killed or seriously injured by their actions.

“Looking back, the kind of things the Angry Brigade did would be far more relevant now,” he says. “We thought, ‘Oh yes, we’re going to win, society is going to be transformed in a socialistic direction.’ But I feel angrier than I ever felt then. The way in which the crisis of 2007 got flipped, so that suddenly it’s not bankers but people living on welfare who are the problem, was extraordinary. These are horrible times.

“At one level, it’s not all defeat,” he says, citing gay rights, the women’s movement and race as areas where things have at least improved in the last 40 years. “Everyone asks why people are so passive, but my experience is that they aren’t, it’s just that a lot of the fights now are defensive – keeping nurseries or libraries open.”

He wrote about his jail time in Bending the Bars, published in 2006, recounting that when he arrived at Brixton prison on remand he found himself beside a giant of a fellow prisoner who asked if he was “one of them bombers”. “Alleged,” Barker replied. “That’s the style, son, you stick to that,” said the giant. He adapted to life inside, reading, listening to the radio – “John Peel never let me down” – and playing the flute and harmonica; he still plays sax with a band in Greece, where he now spends much of his time.

Barker found himself back behind bars in 1990. “I ended up on on this conspiracy rap for importing cannabis and was amazed at how different things were. In a sense, prisons in the 70s must have been the golden days because in a lot of ways the cons were on top. When I went back, so many things we had fought for had been lost. I was shocked by the lack of solidarity and also there was an awful lot of heroin.”

Of the eight defendants, only one has written at length about the case: Stuart Christie, who was acquitted, recounted his own experiences in his memoir, Granny Made Me An Anarchist, and described Barker’s advocacy in court as “worthy of Tom Paine”. Those convicted never went into print about it.

“There was no vow of silence but I don’t think anyone wanted to trade on it in any way,” says Barker. “After we came out, we all got involved in politics in different ways and none of us wanted to discredit whatever we were in – ‘Oh, these dreadful people who were in the Angry Brigade’. To be honest, I don’t think it’s that interesting. I’m not saying this out of false modesty but our support group was more interesting than us.”

Not that there has been any shortage of novels – from Hari Kunzru’s My Revolutions to Jake Arnott’s Johnny Come Home, or screenplays (Our Friends in the North) loosely based on them. There have also been non-fiction books: Anarchy in the UK, by Tom Vague, published in 1997, was reviewed thus by Barker for Mute magazine: “It’s a grisly business being given a book about your own past. There’s this vaguely iconic photo of one’s younger self and the feeling that you’re trapped in a sheaf of yellowing news clippings.”

On release from his second stretch inside, “by luck, I got a job at an overnight news-clipping agency that wasn’t interested in my past, which I did for two years. Then an old comrade kindly showed me a few tricks about book-indexing, so that’s been my main bread-and-butter ever since.” As literary inspirations, he cites James Kelman and Madison Smartt Bell, Kafka and William Faulkner. Kunzru has praised Barker’s novel as a “portrait of a cynical money-hungry culture” that “skewers a moment in history”.

He has two other novels in the pipeline, one about the media, called Radio Signals, the other, a love story, set in Greece in 1981, at the time of a brief political optimism there.

His current political involvement is with a project entitled Loomshuttles, with Austrian artist Ines Doujak, about “textiles and colonialism”, which will take him shortly to Sao Paulo, where it will feature in exhibition form at the Biennale. “Textiles was the first mass tradable commodity, so I’ve been investigating the globalised trade over the last thousand years.” He is also involved with compiling a series of anti-dictionaries called Terms and Conditions that define such key current words and phrases as “not fit for purpose”, “empowerment” and “mission statement”, the publication of which should not lead to a visit from Special Branch. At least, not yet.