By Mechthild Nagel

Transformative Justice Journal

June 2019

Author: Mechthild Nagel

E-mail: [email protected]

Institute: Philosophy Department, SUNY Cortland

Address: POB 2000, SUNY Cortland, Cortland, New York, USA 13045

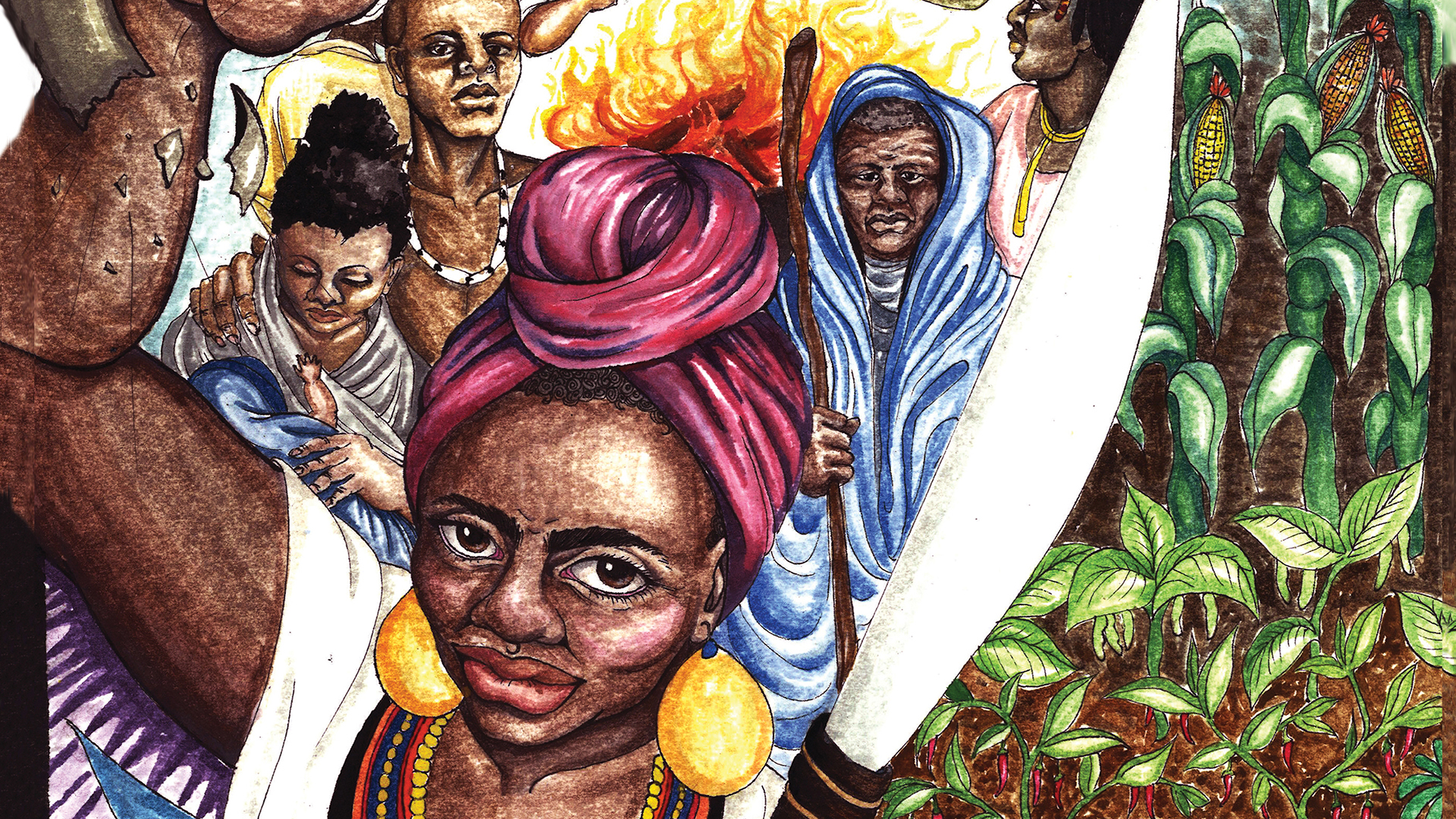

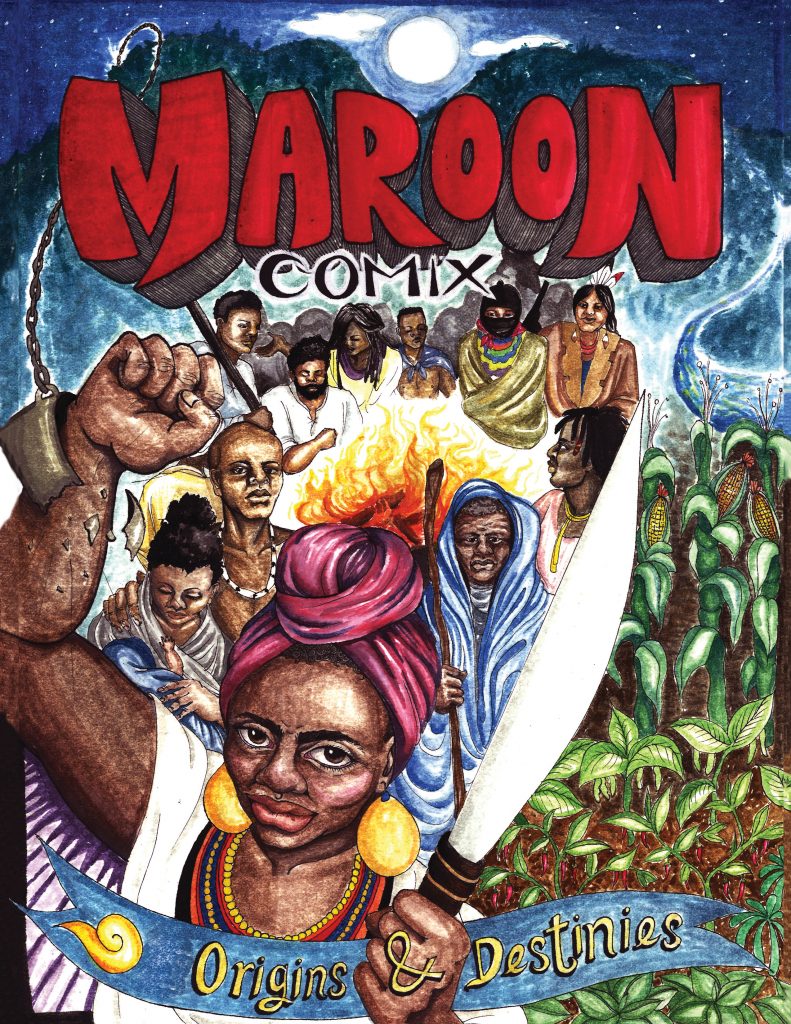

Maroon Comix is a sensational work of art and prose, which honors the legacy of political prisoner Russell Maroon Shoatz. A finely stenciled portrait of Shoatz by Todd Hyung-Rae Tarselli opens the book. Quincy Saul has co-edited the writings of Shoatz in an earlier book, Maroon the Implacable: The Collected Writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz (2013). In fact, this book is a homage to Shoatz, an imprisoned intellectual, because the illustrators and writers draw on his work. Saul closes the comic book with a fabulous “Maroon Library,” thematically organized into the following rich and diverse sections: Maroon History and the Revolt of the Enslaved; Maroon Philosophy; Whiteness and Maroons of European Descent; Marooning in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries; Maroons in the East; Maroon Literature; Maroon Articles; Maroon Music; Maroon Recipes. Moreover, the illustrations are a revolutionary aesthetic feat. With the evocative book cover illustration of Nanny Granny, a Jamaican maroon leader breaking free from her chain with a raised fist and raised sword, the curious reader is already drawn into the political message of liberation that permeates this outstanding maroon book and work of art.

The first chapter titled “Initiation” and illustrated by Songe Riddle opens us up to the illusions of maps and invites us to sojourn off the map. Citations from Gone to Croatan (1994) about the Great Dismal maroons’ legends provide a narrative insurgent history, told from the perspective of colonized Indian nations and enslaved African peoples. Right away, we learn about maroon agency, resistance and the urgency of altering and destroying the white supremacist, colonial script that is so prevalent in US school textbooks. In six chapters, this collective of writers and illustrators takes apart the following corrosive master narratives: enslaved peoples were content about their life-long subjugation; obedient to their masters; fearful of freedom; lazy and cunning. Maroonage, the practices of running away, liberating others, poisoning slavers, is never foregrounded in the “standard” history accounts “on” slavery. It is always a (white) victors’ perspective that twists the record to suggest that maroonage was a futile exercise because the slave catchers were omnipresent and omnipotent. In reality, as the chapter on “Slavery and Liberation,” illustrated by Songe Riddle, emphasizes white and Black indentured servants and enslaved people resisted successfully and ran to the swamps, mountains, forests and other inaccessible places, often joining sovereign Indigenous nations, famously, the Seminole Maroons (p. 12). When the refugees were eventually discovered, these maroon communities fought back, often keeping the colonizers’ armies at bay for years and even centuries from the center of maroon societies, the Palmares to the Carolinas. “The efforts of these men, women and children cannot be matched in world history” (p. 2, citing Shoatz, 2013, pp. 32-34). Because of the success of these guerrilla resistance armies, the colonial powers attempted strategies of appeasement. This worked, in part, with the “treaty maroons,” who remained sovereign under the condition that they returned run-away slaves to the plantations. By contrast, the “fighting maroons” never surrendered and fought to death (p. 13). Throughout the book, maroon societies get named (e.g., the Accompong of Jamaica, the Garifuna of Central America, the Palenqueros of Colombia) as well as famous leaders in the chapter “I am Maroon!,” illustrated by Mac McGill. Here we find Granny Nanny of Jamaica, whose biography is brief (pp. 16-17) but her formidable power is showcased in the last chapter (p. 29). Furthermore, there are Harriet Tubman, Osceola and John Horse of the Seminole, and the Haitian revolutionaries. “In 1791, in Bois Caïman, Haiti, the warrior love goddess and ‘Mother of Haiti’ Ezili Dantor possessed the Haitian high priestess, mambo Cécile Fatiman. She then crowned the African revolutionary maroon and houngan Dutty Boukman with her scepter, invoking and convoking the Haitian revolution” (p. 23). Drawing on Shoatz’s analyis (2013), Saul makes clear that maroon societies drew on spiritual and religious leadership to sustain their diasporic communities against the constant onslaught of imperial armies that threatened their way of life. Haiti, of course, emerges as “the only country in world history established by formerly enslaved workers” (p. 23, citing Shoatz, 2013, p. 119). Thanks to the power of maroons’ resilience, Haiti is the only nation state emerging free from colonialism and enslavement, and it has had to pay a high prize for such audacity—and the hope it brought to millions of enslaved people in the Americas, as well as the shockwaves of terror, the republic sent to slavers. One maroon of Venezuela, José Leonardo Chirino, witnessed the Haitian Revolution and led an insurrection of Indigenous and African maroons, basing his demands on the Haitian and French Revolutions. Saul also pays tribute to Afro-Indigenous-Venezuelan spiritual leader María Lionza who became immortalized as goddess of nature, unifying the African, Indigenous, and European maroon cultures (p. 24). The split between treaty maroons and fighting maroons is exemplified in the conflict between Ganga Zumba and Zumbi. Ganga Zumba, king of Palmares, negotiated with the Portuguese, leading a community of tens of thousands of citizens. After the pact with the colonial power in 1678, Zumbi led a revolt against Ganga Zumba (p. 27). Again, it would have been helpful to add more detail to these very short biographies, especially for readers who know very little about the complexities of maroon philosophies. To the editor’s credit, he foregrounds women’s roles as spiritual leaders, community workers and resistance fighters. Queen Mother Moore is mentioned, born as free woman in 1898 in Louisiana, and early supporter of Marcus Garvey’s movement and received the honorific title Queen Mother by the Ashanti people of Ghana. Moore was an internationalist and called for reparations for descendants of U.S. slaves. The Black Liberation Army and its imprisoned fighters are mentioned, along with Russell Marron Shoatz, who earned his honorific title, “Maroon,” when he escaped from a state prison in Pennsylvania (pp. 31-33). The book shows that “the prison of slavery” morphs into “slavery of prisons,” in the famous words of maroon fighter Frederick Douglass and Angela Y. Davis.

The chapter “The Dragon or the Hydra?,” written and illustrated by Seth Tobocman, also brings an intersectional dimension to the conversation. Tobocman addresses contemporary tactics of struggle against oppression in all its forms, including the struggles of LGBTQ people globally. Drawing on Shoatz’s tropes of dragon and hydra, Tobocman points to the age-old controversy of effective guerrilla warfare—is it diffuse leadership or hierarchical leadership that proves to be most successful? Using the example of Haitian history, we are lead to believe that thy hydra has the upper hand when fighting oppressive powers. When one charismatic leader is killed, others will rise. In addition, if some leaders get coopted such as treaty maroons, others will continue their work of resistance autonomously.

A future Comix books on maroon life and philosophies might want to focus on prominent contemporary maroon communities and how they differentiate themselves from utopian or religious communities or ecovillages, for that matter. This is briefly addressed in the last chapter “Modern Maroons,” illustrated by Hannah Allen, Emmy Kepler, and Songe Riddle. They give us examples of the Zapatistas in Mexico, Julius Nyere’s vision of Ujamaa in Tanzania, the Sarvodaya Shramadana movement of Sri Lanka, and the maroons of Rojava in the greater Kurdistan region. What is common of them are a basis democratic philosophy of reclaiming of the commons by oppressed peoples; promoting women’s leadership and educational opportunities for women; and advocating anticapitalist principles as espoused by the people of Cuba and Venezuela. The simple question of how does one commit oneself to maroonage receives a surprisingly simple answer: start community gardens (p. 56)!

In this book, political prisoners Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Move 9 are mentioned, somewhat inaccurately under the heading of Black Liberation Army (p. 31). It would be good to write a separate Comix Book about their epic struggles with the City of Philadelphia, the Fraternal Order of Police and the FBI. So far, their insurgent perspectives have been told in a few zines and Mumia’s books.

References

Sakolsky, R. & J. Koehnline (1994). Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American dropout culture. New York: Autonomedia.

Shoatz, R. M. (2013). Maroon the implacable: The collected writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz (F. Ho & Q. Saul, eds.). Oakland, CA: PM Press.