By George Longenecker

Rain Taxi

June 2016

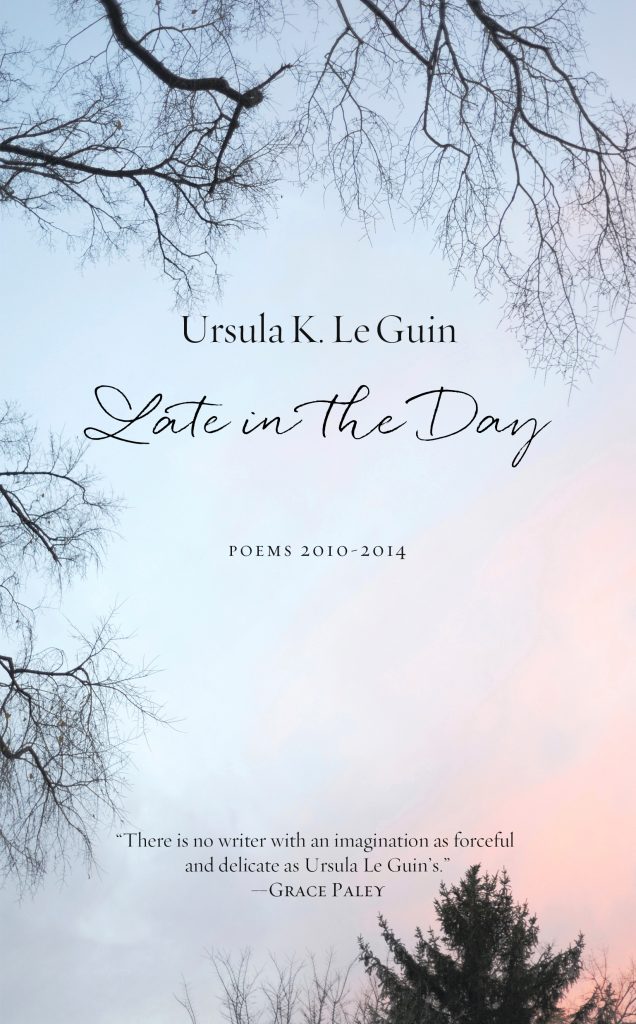

Ursula K. Le Guin’s newest book includes poems, an essay on poetic cra , and a postscript on the state of literature. The poems are well cra ed, each with a poignant message about humanity or nature. Le Guin says in her forward: “by demonstrating and performing aesthetic order or beauty, poetry can move minds to the sense of fellowship that prevents careless usage and exploitation of our fellow beings, waste and cruelty.” In both cra and theme, this new collection meets her ideal.

Le Guin is better known as a novelist, the author of The Le Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, Earthsea, and so many others. Throughout her career, however, she has also been a poet. Her new collection is a worthy addition to her lifework, in which she has continually looked at the relationship of humans to the natural world and sought solutions to con ict and violence.

In “The Old Music” she uses the form of Goethe’s “Nachtgesang”:

The tunes of my own choosing

all sounded false and wrong

I sought a newer music,

I found an older song.

In returning to an older song, Le Guin uses traditional forms, free verse, and “free form.” She says: “By free form I mean a discernible pattern—involving a regularity, repetition of stanzas, line lengths, metric beat . . . that is unique to a certain poem.” “The Canada Lynx,” here in its entirety, is free form:

We know how to know and how to think

how to exhibit what is known

to heaven’s bright ignorant eye

how to be busy and to multiply.

He knows how to walk

into the trees alone not looking back,

so light on his so feet he does not sink

into the snow. How to leave no track,

no sound, no shadow. How to be gone.

Here Le Guin shows her trademark respect for the environment; with irony and humility, she acknowledges that the lynx may know more than we imagine. But she also exempli es the kind of freedom she es- pouses. “We can use rhyme, meter, repetition, however and whenever we choose—in conventional forms, or semi-conventional forms, or in once-only patterns we discover or invent. This, I think, is true freedom of verse.” In “Artemisia Tridentata,” she uses end rhyme and a single quatrain:

Some ruthlessness be ts old age.

Tender young herbs are generous and pliant,

but in dry solitudes the grey-leaved sage

stands unforthcoming and de ant.

She may be de ant—she’s an unapologetic anarchist and feminist, and certainly a literary sage—however Le Guin is anything but unforthcom- ing and ruthless. Goethe, in “Nachtgesang,” wrote: “Those eternal feelings / li me sublimely high, / away from the earthly crowd.” As she observes the world, Le Guin is as sublime as Goethe and yet more grounded in solid form, imaginative imagery, and empathy.

In the book’s postscript, Le Guin says, “Resistance and change o en begin in art . . . I’ve had a long career as a writer, and a good one, in good company. Here at the end of it, I don’t want to watch American literature get sold down the river. We who live by writing and publish- ing want and should demand our fair share of the proceeds; but the name of our beautiful reward isn’t pro t. Its name is freedom.” With such a view, Late in the Day is a tting capstone to Ursula K. Le Guin’s long career. The poems, with their diverse topics and varied forms, show versatility and compassion.