By Russell Holden

Idrottsforum

October 1st, 2015

As the worst European refugee crisis since 1945 continues to unfold, one of the few pleasing aspects of the horrors confronting the swathes of humanity advancing westward has been the engagement of increasing elements of European football with the plight of those escaping persecution and economic impoverishment. The displays of solidarity from football clubs ranging in size from Bayern Munich, to Swindon Town and Dulwich Hamlet confirms the view persuasively argued by Gabriel Kuhn in his new work Playing as if the World Mattered, that not all sport, be it team or individually based, is endemically scarred by commercialism, corruption and what he terms reckless competition.

Organised sport has long managed to have both administrators and activists who have sought to use it as a vehicle for promoting social change, dating back to the emergence of the workers’ sports movement in the early twentieth century, whilst more recently utilising the American Civil Rights and the Anti-Apartheid movements as stimuli for generating progressive change. As well as producing larger than life figures, social change has seen sports fans increasingly reclaiming the games they worship from undemocratic associations and national federations as well as greedy owners and corporate interests. However, much work is still needed, most notably within the realms of international football and cricket.

Kuhn’s analysis of how, rather than why, sport is a key social force in shaping political change is based on a three-fold analysis. Yet, by far the most interesting and revealing section is the concluding chapter, which outlines today’s grassroots and community sports movement. His analysis incorporates elements of community organisation, ethics and direct democracy as well as highlighting the increasing weakness of many sport organisations as portrayed by campaigning journalists.

The analysis opens with a retracing of the workers’ sport movement, which he correctly asserts was the most radical attempt at changing the entire characteristics of sports on a grand scale. The movement was not only a key part of the proletarian culture of the time, but it also granted the worker more influence than other worker organisations as it provided real manifestations of the ideals being projected notably through organisations such as The German Workers Cyclists Association. This body became not only one of the biggest workers’ sports organisations maintaining its own bike factory, workshops, inns, cottages and insurance systems; in 1928 it became central to the newly constituted Sozialistiche Arbeiter-Sport-Internationale (SASI). Yet by 1945 its infrastructure had been destroyed and its successor the Confederation Sportive Internationale Travailiste et Amateur (CSIT) never developed a high profile, culminating in its demise with recognition granted by the International Olympic Committee in 1986. However, at times it is not entirely clear what audience Kuhn is hoping to secure as very specific detail sits alongside some elementary facts.

Kuhn next moves on to portraying the role of sport in the civil rights struggle, demonstrating how athletes, managers, fans and journalists have attempted to influence sport. Whereas chapter one focused largely on organisations, here Kuhn chooses to focus far more on the role of individuals and only latterly on events and institutions. In so doing, he charts the actions of athletes Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente and journalists Lester Rodney and CLR James, before considering anti-colonialism and the political and social unrest of 1968 and its impact on the Olympics and Anti-Apartheid movement. Unfortunately this part of the book reads more like a catalogue of information, making the assumption that the reader is lacking substantial basic knowledge, as opposed to taking the opportunity to offer more insight into the repercussions of these key developments.

However, the concluding element of Kuhn’s analysis is the most interesting. The phenomenon of progressive supports culture most notably, though not exclusively evident in football (he quotes instances from hockey) is a key factor for grassroots democracy and healthy community ties in sports as demonstrated in fans efforts in the creation and the emergence of FC United, FC Wimbledon, Austria Salzburg and Hapoel Kaatamon Jerusalem. Evidence of self management, autonomy and the production of a DIY-zines as opposed to blogs helps to guarantee readership in the stands in addition to fan loyalty.

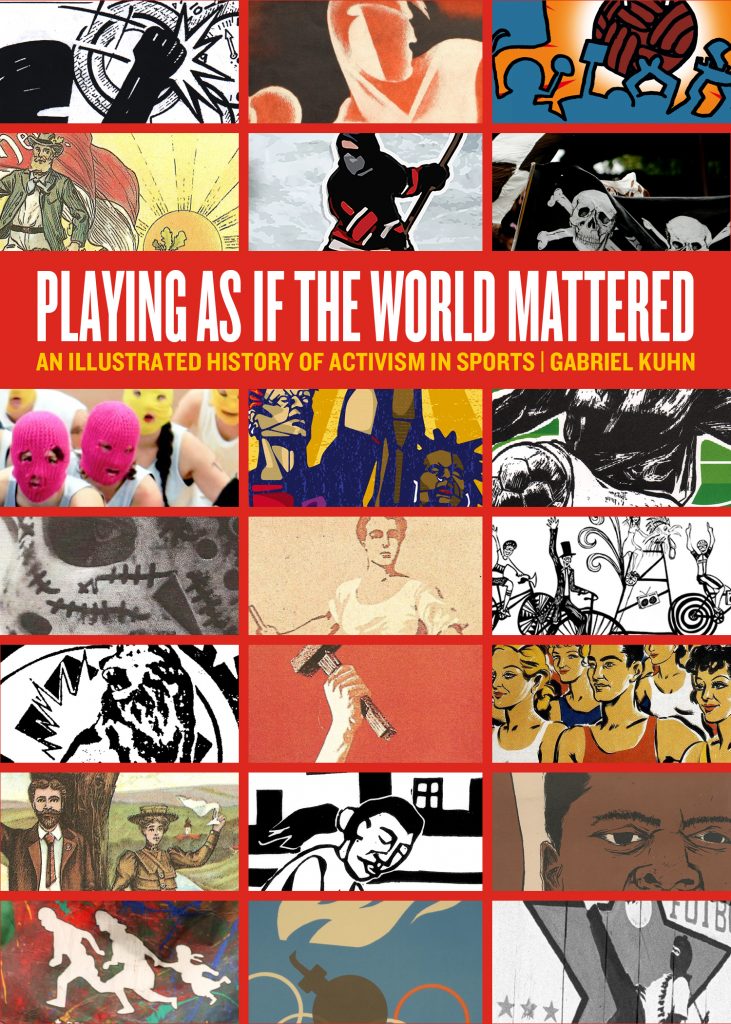

The volume’s immediacy and reach is extended by its use of a large number of full-colour illustrations which give the work a unique selling point . For some, the imagery will be sufficient to generate a purchase whilst opportunities for further engagement and exploration is assisted by an extensive resource list (though no detailed bibliography is evident) thus making this slim, yet enjoyable publication both accessible and affordable. However, at times it is not entirely clear what audience Kuhn is hoping to secure as very specific detail sits alongside some elementary facts. Though it is wise to try to combine the needs of the scholar and the lay reader, both would have benefited from more attention being given to matters such as women’s sport beyond cheerleading and roller derby, as well as to disability sport. Most critical of all is the meagre attention devoted to the actions of player activists such as cricketers Andy Flower and Henry Olonga, rugby footballers David Pocock and Josh Kronfeld, and footballers Socrates and Robbie Fowler.

However, the most pressing exclusion in this publication is the discussion around the discourse of why some sports and some sporting nations are more engaged with activism and the promotion of progressive change, whist others remain either silent, or lack a dynamic purpose in seeking to extend themselves to a wider and more inclusive audience, be it through social justice campaigns such as ridding teams of culturally offensive names and mascots in American sport (Washington Redskins and the Chicago BlackHawks) or in more directly confronting issues such as homophobia.

Although, as Kuhn correctly maintains,the intention is not to weigh down the pleasure and excitement of sport with political and moral baggage, the task of illustrating how sport can weave its magic as a tool for promoting change and fighting tyranny is a message that has to be taken to the masses. Kuhn has provided a very useful starting point, but the key is to ensure that the essence of his agenda is discussed widely within new and old media so that the mainstream sports fan reflects more on the reasons behind why a myriad of migrants and small number of refugees increasingly populate our favourite and least favourite teams, though not their management structures.