By Ben Terrall

San Francisco Bay Guardian

I met Eric Drooker when we were both callow teens experiencing the joys of a coed Quaker socialist hippie camp in Vermont. We skinny-dipped, which was part of the camp’s official policy, and smoked pot, which wasn’t. Drooker has lived in the Bay Area since the mid-1990s, but his art is closely associated with New York City. A lanky, laconic man in his late 40s, he was born and raised in Manhattan, and the city still dominates his imagery. This is true of his wordless graphic novel Flood: A Novel in Pictures (Dark Horse), which won an American Book Award in 1993. It also applies to the haunting silent ballad Blood Song (Harvest Books), published in 2002.

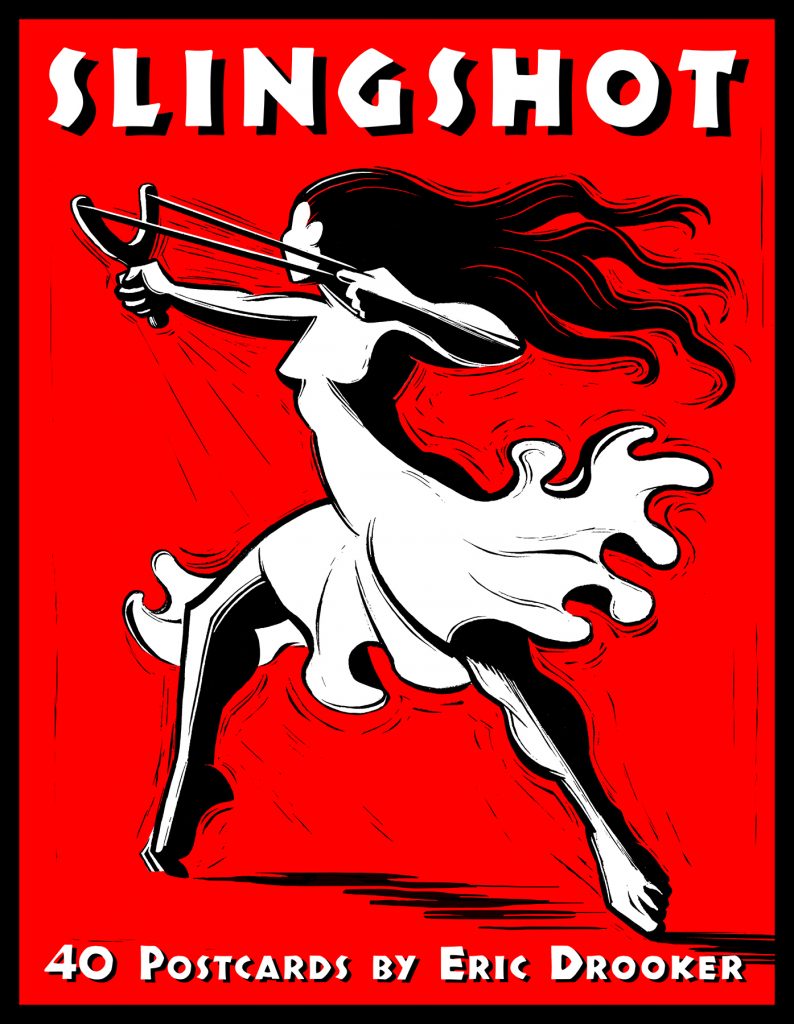

Yet Drooker is perhaps best known for oil paintings that grace covers of The New Yorker — in early September last year, his 15th cover for the magazine appeared on newsstands. Some of these paintings are also included in 2006’s Illuminated Poems (Running Press), which pairs his art with writing by the late Allen Ginsberg. Most recently Drooker published a book of postcards titled Slingshot (PM Press, 68 pages, $14.05). It consists of 32 images created with razor blade on scratchboard.

Drooker’s work is widely disseminated in leftist circles, at times in ways that make the idea of a body politic quite literal — the PM Press Web site notes that his art is “plastered on brick walls from New York to Berlin, tattooed on bodies from Kansas to Mexico City.” He’s largely bypassed the more lucrative realm of art galleries, while allowing activists to access and use (via www.drooker.com) his images free. “I enjoy working on diverse projects that will be seen by a cross-section of the public — not just the gallery-goers,” he says.

The grandson of lower East Side socialists, Drooker was born at the tail end of the post-World War II baby boom. As a teenager, he began participating in progressive politics on a neighborhood level. Early influences on his artistic style included the woodcut novels of Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward and the underground comics of Robert Crumb. During his time in Manhattan, Drooker was active in the late-1980s struggles against gentrification, and in countless antiwar campaigns. Many of the images on display at www.drooker.comstem from those political battles. Today, he believes his hometown has “become inhospitable” to anyone other than the wealthy. “It’s not even a city for the middle class anymore,” he says. “Unless you have big money, the message is: don’t show up.”

Nonetheless, Drooker still dreams about New York: “It wasn’t until I moved away from Manhattan that I became more obsessed with it, and started to really appreciate its significance.” He calls Manhattan “the archetypal city,” and admits that its infrastructure continues to fascinate him. This quality is apparent in the meticulously detailed attention that his work pays to water towers on rooftops, subway tunnel walls, and myriad types of urban pedestrians.

As a youth, Drooker spent many hours watching vintage cartoons. His sense of humor sometimes betrays a still-evident love for Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. He also haunted New York’s repertory movie houses in the 1970s, where he watched films made by the era’s anti-Hollywood rebels, and giants of international cinema such as Akira Kurosawa, Luis Buñuel, and Federico Fellini. Given that much of this impressively prolific artist’s longer form work has the narrative feel of both classic animation and the silent films of Charlie Chaplin, it isn’t surprising to learn that he’s been collaborating with an SF animation studio on an animation project for the last year.

Given Drooker’s decades of political engagement, it’s no surprise that he’s opinionated about the political challenges artists face today, from economic instability and increasing gaps between rich and poor to global war and global warming. He cites Sue Coe (“amazing, hard-hitting”) and Seth Tobocman as two favorite peers. Drooker is a long-time contributor to World War 3 Illustrated, the comics collection Tobocman cofounded in 1980. He has a new piece in the next issue, due soon.

Drooker maintains that the most common contemporary political art is “right wing”: namely, advertising imagery, a form he considers “as much propaganda as any mural Diego Rivera did.” He says he sympathizes with people who produce commercial art to keep their families fed, but that the work is “selling you this myth of consumer culture: ‘Buy this and maybe you won’t feel so bad.'”

“We’re surrounded by political art wherever we turn,” he added during a follow-up e-mail discussion. “Advertising art is ubiquitous, it grabs us by our emotions — as all art does — and tries to sell us things. Its aesthetics are powerful, and its politics are clear. The mural-sized billboards in our public spaces were all created by artists who went to art school. What is the political message? Faith in consumerism. Until the Renaissance, artists were employed by the church. What was the message of medieval religious art? Fear god. Worship a Jewish guy being tortured to death on a cross. Obey the Vatican — or else.”