By Janet Jamieson

Youth Justice 2012

Given the wide array of subject matter, this is a rich text that offers the reader a comprehensive insight into past and present developments in the field appealing to both academic and professional spheres. Practitioners should consider carefully how to incorporate elements of the material in their own work and be encouraged to discuss with their respective service the most appropriate and effective way to use a number of the assessment tools to promote consistent collaborative practice.

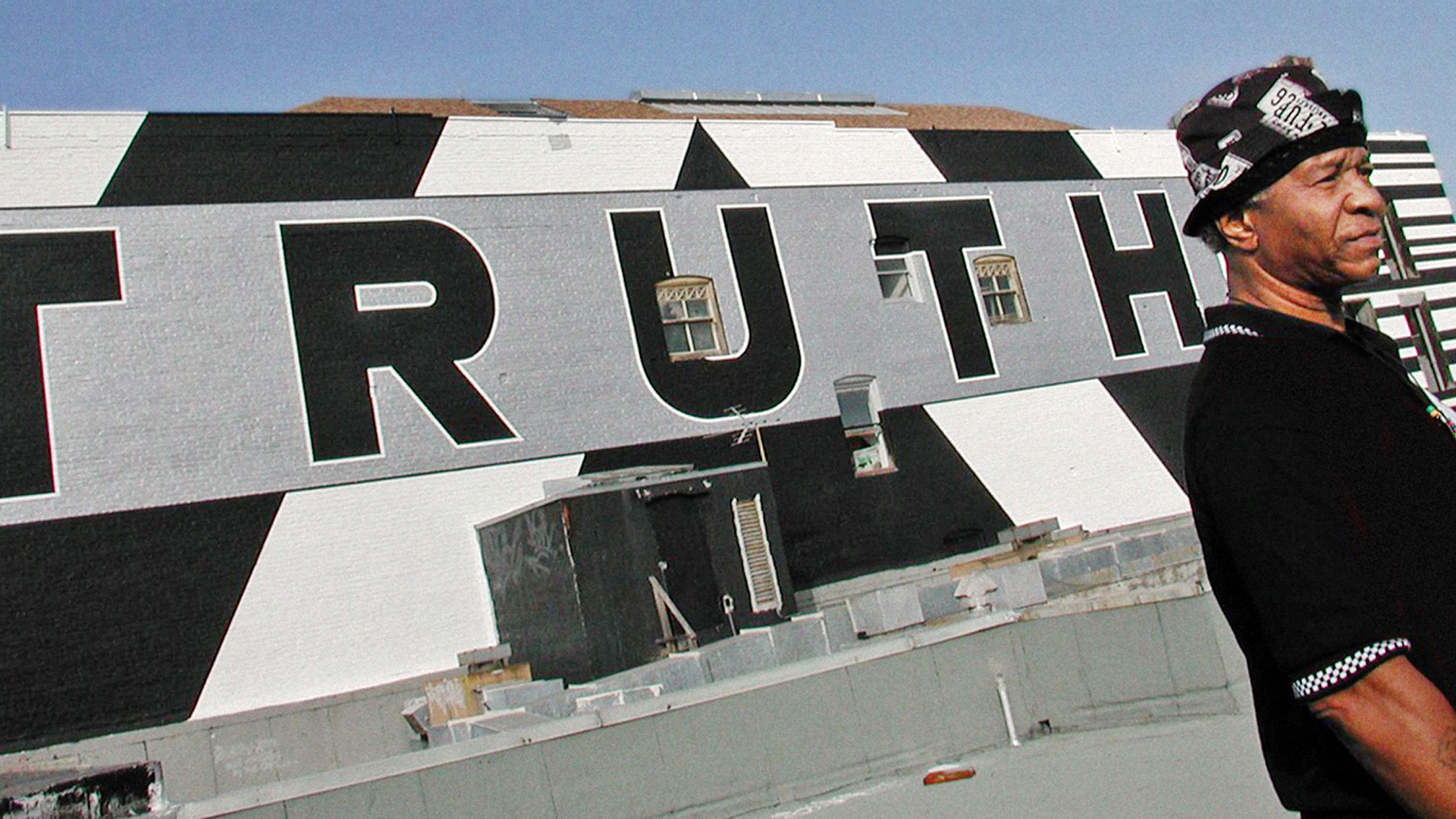

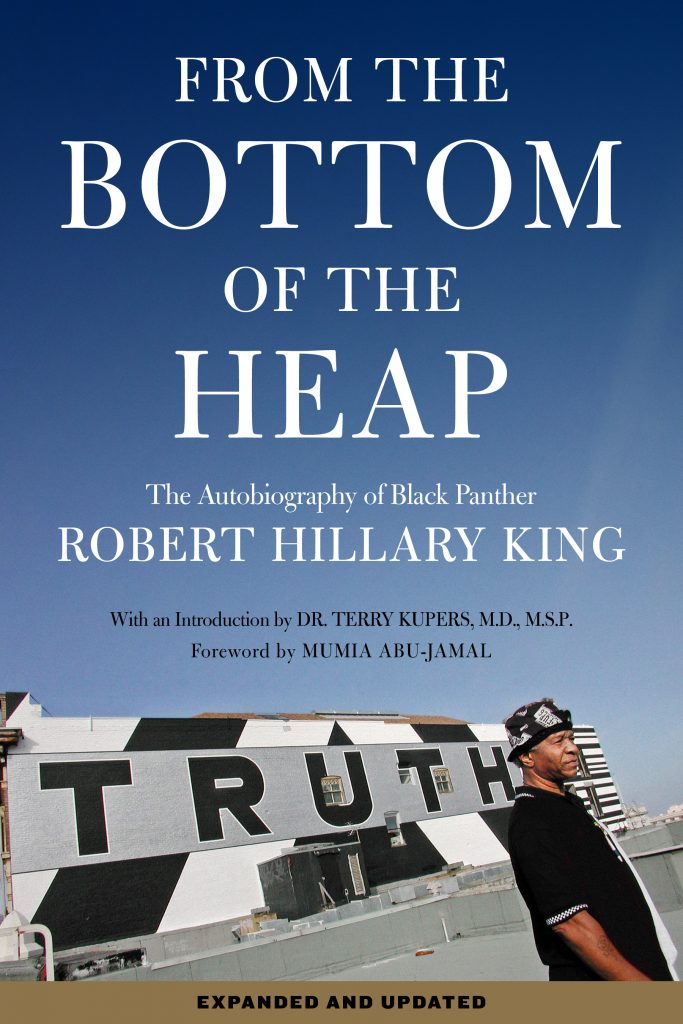

On Wednesday October 12 2011, Robert Hillary King came to speak at Liverpool John Moores University to launch the 2011–2012 seminar series organized by the Centre for the Study of Crime, Criminalisation and Social Exclusion (see http://www.ljmu.ac.uk/HSS/ccseseminarseries.htm). The event involved showing the film In the Land of the Free which documents the story of the “Angola 3″—and a question and answer session with Robert King, the only released member of the “Angola 3” to date. It attracted an audience from academic, activist and community groups across Merseyside, and beyond, and proved an exciting, inclusive and inspiring event. Robert’s presentation was characterized by humour, humility, charisma and, of course, politics. After the formal presentation he signed books, talked and had his photograph taken with many members of the audience and over dinner he generously spent much of the evening chatting to undergraduate students about his life, his travels, and the case of the “Angola 3.” His warmth to all he encountered and the enthusiasm which he brought to the evening attest to his prowess as a political activist, and as a committed educator and campaigner on miscarriages of justice. Reading his autobiography in the immediate aftermath of the LJMU event did not in any way dis- appoint. Over twenty-three chapters, a postscript and five appendices the reader gains significant and powerful insights into the legacy of slavery in the United States and its justice system and the importance of the Black Panther Party to Robert Hillary King’s survival of thirty-one years of incarceration.

Robert’s early life is outlined in Chapters 1–14 and his formative experiences will chime with those with interests in youth justice. Abandoned by his mother, he was lovingly brought up by his maternal grandmother in conditions of hardship and poverty. At the age of thirteen, he was reunited with his birth father and taken to live in a new town. The complexities and tensions which unfold in the relationships with his father’s new family result in Robert developing a stammer, withdrawing from family life and, ultimately, to the breakdown of his relationship with his father. He runs away and goes back to his grandmother. On his return he challenges his grandmother’s authority, leaves school for the seductions of street life and—following a brief excursion into a “hobo” lifestyle—is held in a juvenile detention facility for the first time. By the age of fifteen, he has suffered an array of bereavements, including his grandmother, and has been sentenced to indefinite detention in a state reformatory (for the “offence” of robbery of a gas station that he did not commit). Robert’s reporting of his early years is accessible and characterized by wry humour. However, the seriousness of his task and the purpose of this auto- biography are also to the fore in his ruminations on black masculinity, discrimination and the gross injustices which have been perpetrated against those who, like him, are “born black, born poor” (25) and spend most of their lives in prison.

While Robert freely admits that an inability to find secure employment with a living wage launched him into a “direction contrary to the acceptable modes of society” (132), he was to spend many years incarcerated for crimes he did not commit. Chapters 15–22 address his experiences in adult prisons, and most significantly the years he spent incarcerated in Angola State Penitentiary (formerly a slave plantation). These chapters provide an excoriating critique of the inhumanities and racism endemic to his experiences within the U.S. prison system and offer a searing indictment of a “justice” system which he characterizes as “caring little about the guilt or innocence, especially of Black subjects” and as deliberately and wantonly “deficient” and “gullible” (158).

It is while incarcerated in Angola that Robert, alongside Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, became active members of the only prison-recognized chapter of the Black Panther Party. He notes that the significance of his membership of the Black Panthers was that it provided him with a means “to put the happenings of my individual life into a broader perspective” (165). However, it was also to have a devastating impact on the remainder of his experience of incarceration. The peaceful non-violent protests instigated by the Black Panthers—in the form of hunger and work strikes—brought him and other party members to the attention of prison, state and federal officials. This activism, and prison officials’ desire to punish it, led to King, Wallace and Woodfox being accused of the killing of a young prison guard, Brent Miller, and their long-term solitary confinement for this “crime.” As Chapter 23 details, Robert’s release from Angola was not easily secured. It relied on the commitment and persistence of his lawyer, his family and his supporters and was subject to the legal compromise that he plead guilty to “conspiracy to commit murder” in relation to a crime he did not commit, and could not have committed, not being incarcerated in Angola at the time of the murder. Robert served twenty-nine of the thirty-one years he was incarcerated in solitary confinement. Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox are still incarcerated in Angola and both have served almost thirty-nine years in solitary confinement.

This autobiography is a powerful and engaging read. Academically it compliments and supports Loïc Wacquant’s (2009) Punishing the Poor thesis which argues that neo-liberal priorities have culminated in the retrenchment of state welfare provision in favour of workfare and prison fare (the mass imprisonment of identifiable groups of the population) as a means for the state to assert its authority. It also resonates with a UK context where recent statistics reveal that 26 percent of the prison population are from BME groups, with BME persons being disproportionately more likely to be stopped and searched, arrested, sentenced to immediate custody and subject to longer sentences than white people (Ministry of Justice, 2010). As such, for those interested in—and committed to combating—institutional injustices it is an essential read.

Since leaving prison in 2001, Robert Hillary King has tirelessly campaigned for the release of the remaining members of the “Angola 3” in a bid to fulfil his promise that “even though I was free from Angola, Angola would never be free of me” (201). Hearings for Herman Wallace’s and Albert Woodfox’s legal cases are scheduled for Spring 2012. Robert and his supporters are asking people in the UK to join them and do what they can to help. For readers who may be interested in learning more follow www.Angola3.org

References

Ministry of Justice, “Race and the Criminal Justice System: Statistics on the Criminal Justice System 2010,” http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/statistics-and- data/criminal-justice/race.htm.

Wacquant. L. Punishing the Poor: The Neo-liberal Governance of Social Insecurity. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2009.