by Barbara H. Chasin

Socialism and Democracy

October 21st, 2016

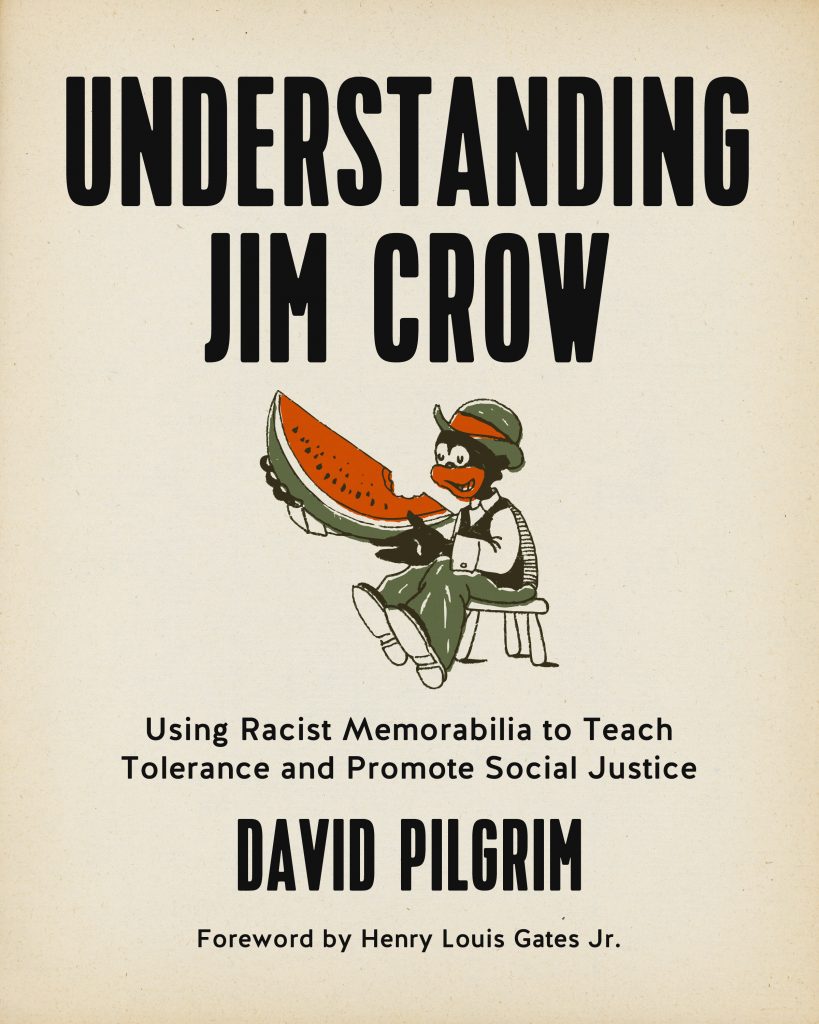

David Pilgrim’s Understanding Jim Crow is a look back at the images that helped justify the racist system that existed in the south from the end of Reconstruction in about 1877 until 1965 when the successes of the Civil Rights Movement ended the legalized separation of African Americans and whites.

The US version of an apartheid system was enforced by horrific violence. As with other instances of inequality, however, an ideology was created that legitimized it for the perpetra- tors and for all those who acquiesced in it. That ideology and the ways it was disseminated are the subject of this book.

Pilgrim, himself African American, was at once fascinated and disgusted, as an adolescent, by racist memorabilia. Over the years, he collected more than a thousand racist images and objects. He refers to these as “garbage” but nonetheless finds them useful for teaching tolerance and promoting social justice. He became a sociol- ogist, joining the faculty at Michigan’s Ferris State University in 1990. Six years later he established “the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia” there.1 At first the objects were from his own collection, but he continued to enlarge the holdings and has added objects pro- duced after legalized segregation ended in the 1960s. Visitors to the museum can view everyday pieces conveying the message that those of African descent were stupid, ugly, hyper-sexed, and not fully human.

Pilgrim gives a detailed description of the exhibits, discussing the meaning of a number of them. One of the book’s useful themes is that stereotypes change as social context changes. During slavery those of African descent were usually described as docile and unproductive. Male slaves were portrayed as Uncle Toms, loyal and dependable, while Mammy was a loving, faithful female. Children were happy- go-lucky picaninnies who weren’t even likely to be properly dressed by their ignorant black parents. Whether male or female, those of African descent needed whites to manage their lives and make them productive. No whites needed to feel guilty because the slaves were happy, or so the story went.

But when slavery ended in 1865 and 11 years later federal troops were withdrawn from the south, southern elites found ways of creating a labor force comprised of super-exploited and subservient former slaves. There was no powerful group that opposed this and racist forces were free to create a system of terror against blacks and anyone else posing a threat to white supremacy, including labor organizers.

The Jim Crow system bolstering white supremacy served to break up the fragile but important alliance that had been developing between working-class whites and blacks in the period of Radical Reconstruc- tion. During this time more African Americans were elected to public office than at any time in US history, desegregated public edu- cation began in the South, and there was a social mingling that later became impossible.

Racism

was used to undo all these advances. Keeping blacks from exercising the

democratic rights supposedly guaranteed by the 14th Amendment meant

white elite interests would be served. More details on this historical

context could add to the book’s impact. The lynch mob, shootings,

beatings, evictions, etc. drastically reduced the numbers of black

voters. For example, in Louisiana as late as 1898, 130,000 blacks were

still on the voting rolls; by 1906 the number was 1,342.2 In the 1970s

North Carolina still required literacy tests for

voters.3 Then as,

now, powerful institutions, including the Supreme Court, made racism an

integral part of American life. Very few opposed the home-grown

terrorism destroying black lives.

The list of racist objects described in this book is long, covering vir- tually any household object or item of popular culture, including salt and pepper shakers, ashtrays, postcards, note-pads, cartoons, and books, including those for children such as Little Black Sambo. Carnival “games” used African men as targets, normalizing violence against them. Popular songs and minstrel shows made racism fun, at least for some. The stereotypes were aimed not only at whites but at black self-conception. Norms and laws governed everyday white and black interactions so that these could not be egalitarian. Pilgrim has a long and useful list of these rules.

Summarizing the messages in the museum’s displays Pilgrim writes, “Blacks have been portrayed in popular culture as pitiable exotics, cannibalistic savages, hypersexual deviants, childlike buffoons, obedient servants, self-loathing victims, and menaces to society” (5).

New forms for conveying these racist messages appeared with the advent of radio, films, and television. Older readers might remember the Amos & Andy programs, or the servant who went only by the name Rochester on the Jack Benny show. Pseudo-scientific writings supported notions of white superiority, something which has not dis- appeared today. Racist objects are still being produced. Pilgrim men- tions, as examples, targets with Trayvon’s Martin’s face on the center and the game Ghettopoly, created in 2003, with projects and crack houses replacing Monopoly’s buildings.

One example that Pilgrim doesn’t mention is the popular Currier & Ives prints and calendars which included a print series called Darktown Comics, which like so many other depictions showed African Americans as incredibly stupid – like firemen who couldn’t see the fire in front of them.4

While describing the objects and their messages, Pilgrim also describes aspects of the Jim Crow south that very few who had not experienced it would be aware of. For instance, black men who owned new cars would wear chauffeur caps when driving so as not to arouse envy and possible violence from whites. When buying clothes, African Americans would need to know their clothing sizes since they were not allowed to try on clothes that might also be donned by prospective white customers at department stores.

This book is evidence of the validity of the William Faulkner saying “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” While the legal underpinnings of racism have been mostly abolished, there is still a high degree of racial inequality in the US. In spite of the election of Barack Obama we do not exist in a post-racial society. There have been gains. African Americans are more visible on television, in advertisements, in some occupations, etc. Nonetheless, housing seg- regation persists as described in the sociological study with the telling title American Apartheid. Along with segregated housing come segregated inferior schools, neighborhoods with high levels of unemployment, and a prison-industrial complex based on a system that in numerous ways treats whites and blacks differently from the moment of arrest through incarceration. Court rulings, once again, limit electoral access by reinterpreting the 1965 Voting Rights Act; laws against prisoners and ex-felons and new voter ID laws add to the difficulties African Americans have in being active citizens. Racist messages are employed, especially by Republicans, to win white voters.

This is a horrifying but important book that should be widely read to gain an accurate view of the long history of racism in the US. The Museum challenges its visitors to ask what they can do to fight racism. There is a “Death of de jure Jim Crow” area paying tribute to the “wonderful accomplishments” and heroism of many African Americans. These must be a welcome relief from the “mammies,” “coons,” and “Sambos” the exhibit-goer will have been bombarded with.

Another counter to the demeaning images, not mentioned by Pilgrim, was created by African American photographers. A number are depicted in the documentary “Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photo- graphers and the Emergence of a People.” The photos serve as a remin- der that in spite of the massive propaganda and violence perpetuated by overt and covert racists, resistance was present then as now.

1. www.ferris.edu/jimcrow

2. Richard T. Schaefer, Racial and Ethnic Groups, 7th edition, New York, Longman, 1998,

3. Richard Fausset, “Battle Over Voting Laws Peaks in North Carolina,” New York Times, March 11, 2016, p. A1.

4.

http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1997-06-26/features/1997177066_1_currier-ives-

ives-print-unintentionally-funny;

http://campus.albion.edu/library/archives-and-

special-collections/exhibits/currier-and-ives-darktown-comics/darktown-comics-

historial-context/

# 2016 Barbara H. Chasin Professor Emerita, Sociology Montclair State University Montclair, New Jersey [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08854300.2016.1223825