By Mat Callahan

Red Wedge, originally published in STIR magazine

September 4th, 2015

Image by Hope Asya

Music and memory have always been inseparable. After all, Memory is the name of the Goddess who was Mother of the Muses. The Muses, according to the poet Hesiod, “were nine like-minded daughters, whose one thought is singing, and whose hearts are free from care…who delight with song… telling of things that are, that will be and that were with voices joined in harmony.” They called on Hesiod to sing their praises but they did so with a challenge: “You rustic shepherd, shame: bellies you are, not men! We know enough to make up lies which are convincing, but we also have the skill, when we’ve a mind, to speak the truth.”

That the nine muses were the daughters of Memory and not another Goddess is explained by the fact that their number corresponds to the gestation period of human beings. Memory lay with Zeus nine nights to produce nine daughters and in the marvelous mathematics of myth our story begins with the renewal of human life upon this earth. Memory serves unfolding and rebirth, not the mere storage of information.

This interpretation is supported further by the fact that Memory was the protectress of Eleuther’s Hills-Eleuther meaning freedom in Greek. What greater gift could there be than to rejuvenate our bodies while freeing our imaginations? Therefore, the Greeks of Hesiod’s time thought memory should be studied, practiced and improved in an ordering process that would enable the orator, the poet, the actor or musician to deliver public performance without recourse to writing. Indeed, writing was viewed as a pale substitute for memory, merely reminding when one needed to remember. Writing is an external sign whereas memory comes from within. Therefore writing is less reliable as a source for what it is most important to know. Written words cannot themselves convey the method by which memory must be practiced and made a guarantor of learning. Regardless of what we think of writing now-and in the intervening centuries the phrase “it is written” was used to lend legitimacy to any claim-there is something to be said for this approach, as musicians and actors certainly know. We will return to this point later on. For now, it’s enough to recall that memory is a crucial component of learning. But just as there are different things to learn there are different kinds of memory. And music plays a role in all of them.

The first kind of memory is what I call immediate, or instant recall for present use. This requires the honing of skills by repetition in order to perform specific tasks. It’s not surprising that music would serve as a mnemonic or memory-aid since rhythm and melody are delightful, they unite the body and mind and children in particular quickly and easily respond to them. To memorize the alphabet, times-tables, and other recipes or formulas, simple songs have been devised. Not only does music alleviate the drudgery of repetition and drill but it brings immediately to life the stored information when it has not been used for some time. In fact, scales or rhythms are themselves assemblages of notes and beats by which we remember what to play. It is of course useful that music can be written down and that sight reading is a necessary skill in many situations. But this can only be a supplement or aid for what is ultimately an auditory phenomenon, not a visual one. Music only exists in real time passing into and out of existence on the air which it disturbs so that our ears can perceive it. To learn it requires memorization, repetition and lots of practice. This is immediate memory.

Then there is nostalgia. This word was coined by a Swiss doctor in 1688 to describe a malady common among Swiss mercenaries fighting in France and Italy. It had been called the “mal du Suisse” or Swiss sickness but Dr. Johannes Hofer more precisely described it with two Greek words, “nostos” and “algos”, that when combined meant, “homesickness”. This was triggered by the singing of songs which revived the memory of the Alpine valleys from which the mercenaries had been recruited. Rousseau, in his Dictionary of Music, wrote that this became such a serious problem, leading to desertion, illness or death, that the mercenaries were forbidden to sing these songs altogether.

What I am calling historical memory is distinguished from both the mnemonic and nostalgia by its recollection of actual events in which people took part. While a mnemonic may aid in performing a task and nostalgia may be a longing for a mythical place, the marking of great struggles such as uprisings, revolutions or civil wars, is a specific function of memory that, like the rest is served by music. The classic example is the National Anthem but it is not confined to this. Indeed, a fundamental purpose of balladry the world over is to remember the battles, victories and defeats of oppressed social classes and ethnic groups. Precisely when History is being written by the victor, it is to song we have to look for the perspective and experience of the defeated. Or, to put it another way, songs remind us how temporary victory and defeat actually are. Thus, songs evoke a spirit of resistance, reviving and renewing it, undaunted and unafraid.

This is of considerable importance to musicians learning their craft. All the skills that must be gained in order to perform well and that take years to acquire are specific in both mechanical and cultural ways. Learning to play the guitar, for example, requires that one learn not only the chords, scales, tunings and rhythms particular to the instrument but also those that are particular to certain forms such as blues, jazz, Irish or flamenco, and so forth. This necessarily includes learning songs and other compositions that comprise the canon or archive that make up a musical idiom. Now all of this might go without saying except for the fact that what is often required of musicians is merely formal accuracy or good technique. In fact, we often ignore the feelings and ideas the song was originally intended to convey. Thus, expanding repertoire or increasing virtuosity takes the place of feeling. What this process forgets is that music’s most important quality is spiritual in that it evokes powerful emotions, it moves us. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that musicians not only learn the mechanical and formal aspects of performance but that they learn what inspired the creation of the songs or compositions they are to play in the first place. Blues is not just a style. It is a library of responses, emotional and intellectual, to the conditions faced by generations of African Americans. More particularly, it conveys, often in coded language, a wisdom gained through hard experience under slavery and ever since.

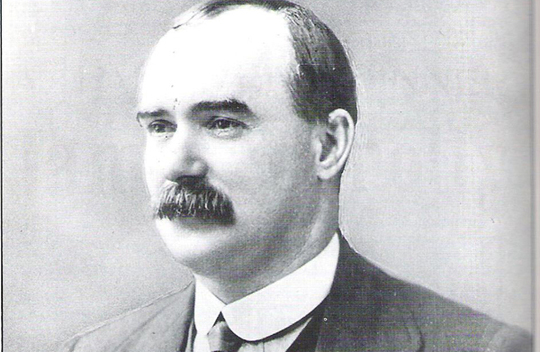

The same can be said of many other forms, for example, Irish music. When James Connolly published his “Songs of Freedom” in 1907, he prefaced the collection with this statement: “No revolutionary movement is complete without its poetical expression. If such a movement has caught hold of the imagination of the masses, they will seek a vent in song for the aspirations, the fears and hopes, the loves and hatreds engendered by the struggle.” Now, Connolly’s statement is itself a part of history but its relevance here is that it accurately expresses one crucial component in the development of Irish music and in a particular way: during an 800 year struggle against English conquest there were many who consciously sought to use music in the service of this struggle thereby enriching music in the process. One song typifying an entire legacy is, “By The Rising of the Moon”. This song was written long after the events it depicts, namely the uprising of 1798, in order to inspire another attempt, the Fenian rebellion of 1867.

How well they fought for poor old Ireland

nd full bitter, was their fate

Oh what glorious pride and sorrow

Fills the name of ninety-eight.

Yet thank god while hearts are beating

Each man bears a burning wound

We will follow in their footsteps

At the rising of the moon.

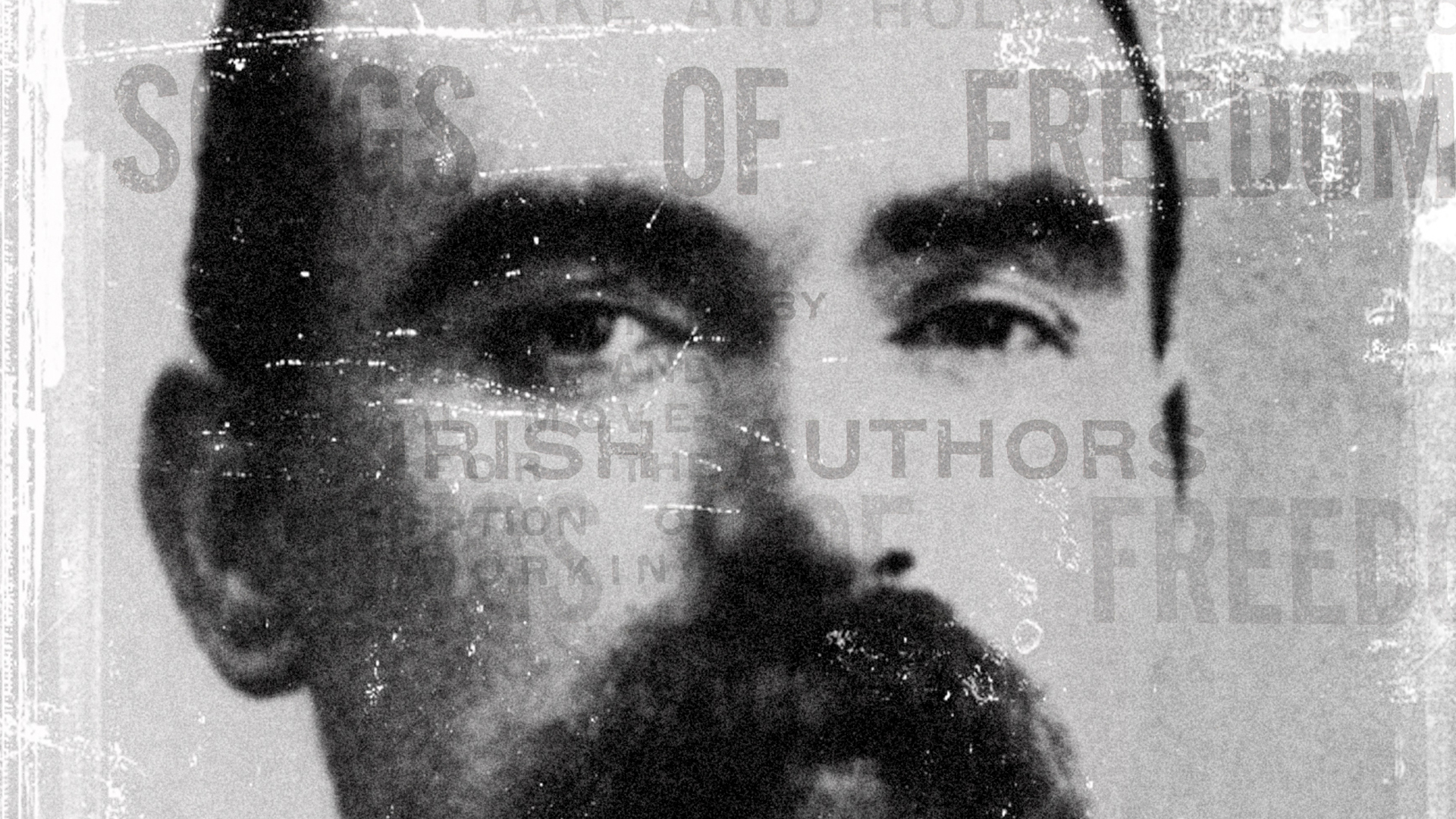

James Connolly

Now how can one hope to capture the feelings that went into this song’s composition and perform them today without knowing at least something of the history involved?

It might be argued, of course, that

this is the job of the ethnomusicologist, the folklorist or even a

producer like T-Bone Burnett selecting songs for a movie such as “O

Brother Where Art Thou?”. It might further be argued that musicians

should simply play well and express their own feelings through whatever

compositional form they choose. What is most authentic and convincing

in any case is one’s own passion and skill, not how well or poorly

informed one is about history or politics. These are valid arguments

with which I generally agree. But they cannot be isolated from the

real situation in which musicians find themselves at any particular

time, including right now. Not only is a great deal of rich experience

written out of the historical record but many formal attributes of the

music of oppressed people are appropriated to be used against them.

This is nowhere more clearly demonstrated than in the history of the

United States both in political terms and in terms of how music was

turned into a commodity by the music industry. The question was

eloquently addressed by Duke Ellington, who, when asked to comment on

Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” said, “Grand music and a swell play but

the two don’t go together…the music did not hitch with the mood and

spirit of the story…it does not use the Negro musical idiom.” (from a

1935 interview in New Theater magazine) Ellington did far more than

comment however. He devoted his own creative effort to “Jump For Joy”,

a highly successful musical of 1941. In “Jump For Joy”, Ellington

directly addressed the representations of Black Americans in musical

theater:Now, every Broadway colored show,

According to tradition,

Must be a carbon copy

Of the previous edition.

With the truth discreetly muted,

And the accent on the brasses,

The punch that should be present

In a colored show, alas, is

Disinfected with magnolia

And dripping with molasses.

In other words,

We’re shown to you

Through Stephen Foster’s glasses.

This is one small but formidable example of the general problem. Musicians are placed in a peculiar position of being the bearers of historical memory at the same time it is often their fate to seek employment by those who’d most like to erase that memory. While the schoolbooks and mass media may succeed in carrying out this erasure, it is virtually impossible to do so with music. In fact, a crucial component of what produced the musical renaissance of the 1960s was the realization on the part of a young generation of white people that the main source of their beloved music was the African-American and more specifically, the suffering, struggling and rejoicing of this people. Clearly, the political struggle for Civil Rights and later for Black Liberation was the main reason people were made aware of this fact and the howling hypocrisies it exposed. Still, music played such an indispensable role in the lives and aspirations of Black Americans that there was no way even the most apolitical musician could remain unaware of the connection between music and history, particularly the history that was being made at that very moment. Besides, the barriers of segregation were becoming less and less effective due in large part to music, particularly its transmission by radio. Radio allowed young people to compare for themselves Pat Boone’s versions of songs written and performed by Little Richard. Race records, only recently renamed Rhythm and Blues, became the prized possessions of hipsters and aficionados, and soon thereafter the crucial element in any dance party. This had, moreover, a significant effect on impressionable young minds. As Steve Van Zandt recently pointed out, “Little Richard opened his mouth and out came liberation.” Here was a sound and excitement that could not be contained by legislation, censorship or banning and burning records. Although such suppression was indeed attempted-and is an important subject in its own right-the point here is that musicians found themselves in a vortex of social conflict that affected music as such. In other words, one could not play any of the burgeoning varieties of rock music without coming into contact with these controversies and in one way or another taking a position. This produced some timeless music that was, at the time of its creation, quite innovative. Outstanding examples include Sly and the Family Stone, Santana and Tower of Power all of whom broke new musical ground by deliberately challenging prevailing norms of what a band should look like, what styles of music could be combined and how the turmoil in society should be addressed. From Sly’s “Stand” to Tower’s “What Is Hip?” it was demonstrated how one could simultaneously honor musical traditions while doing something genuinely new.

Of course this had precedents in previous

generations and it was certainly not the case that the generation coming

of age in the Sixties somehow fell from the sky. In fact, it was to a

large extent the influence of the Folk Music Revival which reached its

apex in the first half of the 1960s that produced two crucial effects

on what transpired in the last half of that decade and beyond. First,

there was the enduring connection between music and the labor movement

which would continue with the subsequent Peace and Civil Rights

movements. From Joe Hill in the early 20th Century, through Woody

Guthrie, Pete Seeger and many others, a long, unbroken tradition had

firmly established a connection between music and popular struggle.

This was, moreover, based on the music miners, textile workers,

sharecroppers and other laborers were making themselves. The second

point is that even when some practitioners of this music became

commercially successful, the tension between the slick, sanitized

mainstream version and the raw eloquence of the original produced a

similar effect amongst young musicians as had the comparison of white

covers of black songs. An entire generation became increasingly

sensitive to the abyss that separates the genuine from the fake, the

authentic from the phony. Even largely innocuous and ingenuous acts

such as the Kingston Trio or We Five were viewed with derision when

compared to The New Lost City Ramblers, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Odetta or

Buffy St.Marie. The dividing line had been drawn with such creative

force that even when Rock n Roll overwhelmed the Folk Music Revival

rejecting many of its musical constraints, the question of the authentic

vs. the fake remained a fundamental criteria of music and society as a

whole. If proof is needed there’s none better than Dylan’s

unforgettable denunciation:Money doesn’t talk, it swears,

Obscenity, who really cares,

ropaganda, all is phony

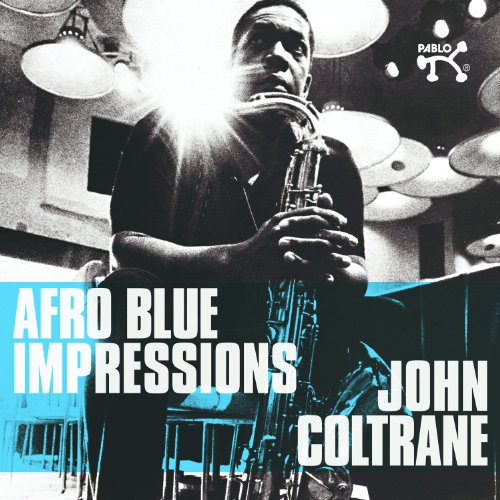

Now forty years later this has a bearing on the question of music and historical memory for the obvious reason that this period is now history which music carries forward even as it is being forgotten or deliberately obscured in much public discourse. After all, music making was altered in significant ways during that period which for better or for worse has had enduring impact on music itself. The point here, however, is that there are specific historical lessons taught by music that both affected popular consciousness on a large scale then and can still be learned from today. Noteworthy examples can be drawn from a vast number of songs such as Dylan’s “George Jackson” or John Coltrane’s “Afro-Blue”, from Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” to the Mother’s “Trouble Comin’ Everyday”, not to mention a host of social commentary for which Zappa was then and is now deservedly admired. Perhaps nothing better represents this than the opening and closing performances in the movie of the Woodstock festival, namely Richie Havens singing “Handsome Johnny”-a pointedly historical text-and Jimi Hendrix’s stunning version of the “Star Spangled Banner”-a wordless statement, powerfully evoking everything entangled in that moment of war and revolution. And these are only the world renowned markers by which a much larger field is indicated. It should not be forgotten that in the main, anonymous multitudes form the rich soil of music making and of history, the driving force ultimately responsible for whatever remains for us to savor, enjoy and learn from. This is not simply an obligatory nod to the democratic masses, either. If the historical memory that music shelters and passes on contains anything at all it is the memory of great popular movements for liberation. Through such music we are reminded of heroes who were people like us, courage that we too may summon and futures that are better than the present or the mythical past.

Cognizant of this fact, one of the main aims of the music industry, from its inception, was to replace this particular function of music with something else. Instead of historical memory, we are offered novelty and nostalgia. This goes back to the origins of Tin Pan Alley and its predecessors in Minstrel Shows and vaudeville. It is demonstrated again by the industry’s treatment of ragtime and the coon song. That this was systematic and deliberate is beyond any doubt. That musicians in particular have suffered the consequences is worthy of another discussion in its own right. But suffice it to say that norms established by weekly hit parades, massive promotional budgets and lavish expenditure to manufacture celebrity, have created a situation in which the feverish recycling of cliches takes the place of genuine innovation and the pathetic longings for a nonexistent homeland take the place of people’s aspirations for a better life. These are the twin incubi on the shoulder of every musician working at his or her craft and have to be confronted head on. The least one can do is to disabuse themselves of the notion that quality or ability have anything at all to do with how one is judged by the music industry. Indeed, taking hold of what music tells of history can be a useful shield against the unalloyed nonsense loudly proclaimed by cretins and bean counters as if they were the wise representatives of the “people”. As if they give a damn about anything except profitability.

Instead, all of us who love music should meet the challenge posed to Hesiod by the Muses. We should aspire to more than being mere “bellies” or animal appetites. We should call upon the Muses to tell the truth and not convincing lies. We should learn from the great reservoir of music that celebrates the real heroism human beings are capable of. And, even as we compose new music and attempt to break new ground, let’s draw inspiration from the feelings and ideas that arise from lived experience. Our own as well as those who’ve gone before.

A version of this article appears in STIR magazine.

This article appears in Red Wedge Issue One: “Art + Revolution.” A copy can be purchased at our shop.

Red Wedge relies on you! If you liked this piece then please consider donating to our annual fund drive!

Mat Callahan is the author of The Trouble With Music and editor of Songs of Freedom: The James Connolly Songbook. A veteran musician, he was a member of the Looters and a founder of the artists’ collective Komotion International.