By Jessica Mills

Maximum Rock N Roll

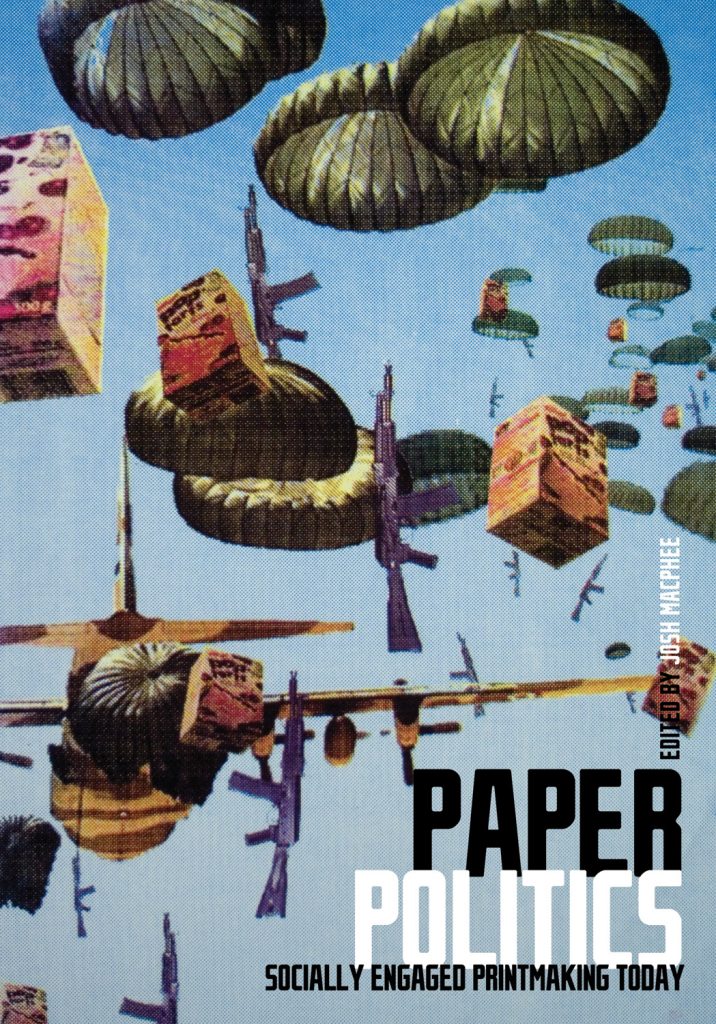

Carrying on the work of artists creating art for more than art’s sake, instead using social justice and global equity-themed art as a vehicle to engage community in political conversation, Paper Politics started out as an exhibition first hung in Chicago in 2004 in the offices of In These Times magazine. This book showcases what became a travelling exhibit (hosted in 11 different cities from 2004-2009) of politically and socially engaged print art.

Though traditional printmaking techniques were used for all the original work, what’s been created and collected here is cutting-edge contemporary. Though the art was created by artist hands and the exhibitions organized and shows hung by collective labors of love with the purpose of building community, mass-production printing was indeed used to create the book.

While the exhibit boasts a cumulative crowd of thousands, the exhibit in book form becomes more portable, practical and accessible. This obviously creates a contradictory question. Traditionally created printmaking stands out from the digital age pack of billboards and bus ads, but can only be printed in small batches by hand. Josh MacPhee asks in his introduction, “If the goal of printmaking is communicating ideas, and we want those ideas to reach as many people as possible, does it really make sense to be printing seventy handmade posters in the age of mass production?”

Following MacPhee’s introduction are two essays and four sections or reproduced prints. The first is Repression – imprisonment, eviction, torture, surveillance, media control, privatization, apartheid, suppression. Repression is followed by Aggression – war, bombing, colonization, invasion, murder, extinction, genocide, rape. Third up is Resistance – liberation, solidarity, organizing, occupation, direct action, uprising, disobedience, struggle. And last but not least, Existence – identity, awareness, movement, communication, creation, transportation, perseverance, joy. Each section showcases about 40 reprints; in total, included are nearly 200 artists and artist collectives from over a dozen countries and over seventy-five cities, suburbs and small towns. The art here is alive with color, style, unity and diversity – from stencil art spray painted on old dumpstered blueprints to precise and fine art intaglios on Arches paper. Each section is interspersed with artist commentary explaining why they print by hand, what they hope to gain and to whom they hope to speak.

The first essay is “Political Art and Printmaking: A Brief and Partial History” by Deborah Caplow. Caplow credits the beginnings of political printmaking to Francisco Goya in the beginning of the nineteenth century and reminds us that political art has earned many an artist hefty jail terms for having had the audacity to oppose injustice, war and corruption.

Caplow also explains why the printmaking medium, say instead of painting or sculpture, lends itself supremely to messages of political opposition; it’s reproducible, has low cost and holds great potential for graphic expressiveness. The essay suggests that graphic political art has never been more popular as the evidence can be found in the form of posters, flyers and stencils on the walls, streets, newspapers and magazines all over the world.

The second essay, “All the Instruments Agree,” by Eric Triantafillou, is an extremely thoughtful and well-written piece on the intersection of art and politics. Starting with vivid description and sharply deconstructed political analysis of the Wheat paste wall on Valencia Street in San Francisco, the essay suggests that ultimately, single-issue political images have the effect of reducing the larger political context in which the image is based down to an oversimplified “us” vs. “them” or “evil” vs. “good” message. They confound the broader message that needs to be communicated in order for the art as political tool to be successful. Triantafillou ends with a call to all fellow left printmakers to unify their politics into a set of shared goals “based on an intransigent desire for total social freedom.”

Paper Politics is for those who recognize that both art and politics are about communication and also about community. As much as it is a collection of individual artists’ prints, the project has proven itself to be a successful exercise in large scale organization. Josh MacPhee writes about the project’s intent, “…a community of printmakers and a more specific audience for our work than the existing ‘anyone that happens to see it on the street’.” Proof of that intent’s success is that a couple dozen of the artists involved with the exhibits went on to become members of the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative, an artist-owned and –run collective and online gallery.

Over the years of the traveling exhibit, artists and audiences have met face to face and wound up building more long-term relationships than a passing glimpse of a wheat pasted poster on the street could ever provide.