By Daniel Tseghay

Rank and File

September 29th, 2016

In 1947, when Jamaican agricultural workers were already making their way to Canada on short-term contracts, Canadian officials resisting the possibility of permanent residency on explicitly racist, and curiously paternalistic, grounds. “The admission to Canada of natives of the West Indies has always been a problem with this Service and we are continually being asked to make provision for the admission of these people,” reads a federal memo. “They are, of course not assimilable and, generally speaking, the climatic conditions of Canada are not favourable to them.” Meanwhile, between 1946 and 1966, 89,680 primarily Polish war veterans and Dutch farmers became seasonal agricultural workers in Ontario. These migrants were largely granted permanent residency status.

Today, despite the change of rhetoric, and the image of colour-blindness, racialized migrant workers in Canada are still exploited and treated much worse than other workers.

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) includes: the Caregiver Program, which was, until November 2014, the Live-in Caregiver Program, consisting of racialized, women care workers from the Philippines and the Caribbean; the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), mainly composed of Mexican and Caribbean workers; the Stream for Lower-Skilled Occupations; and the Agricultural Stream.

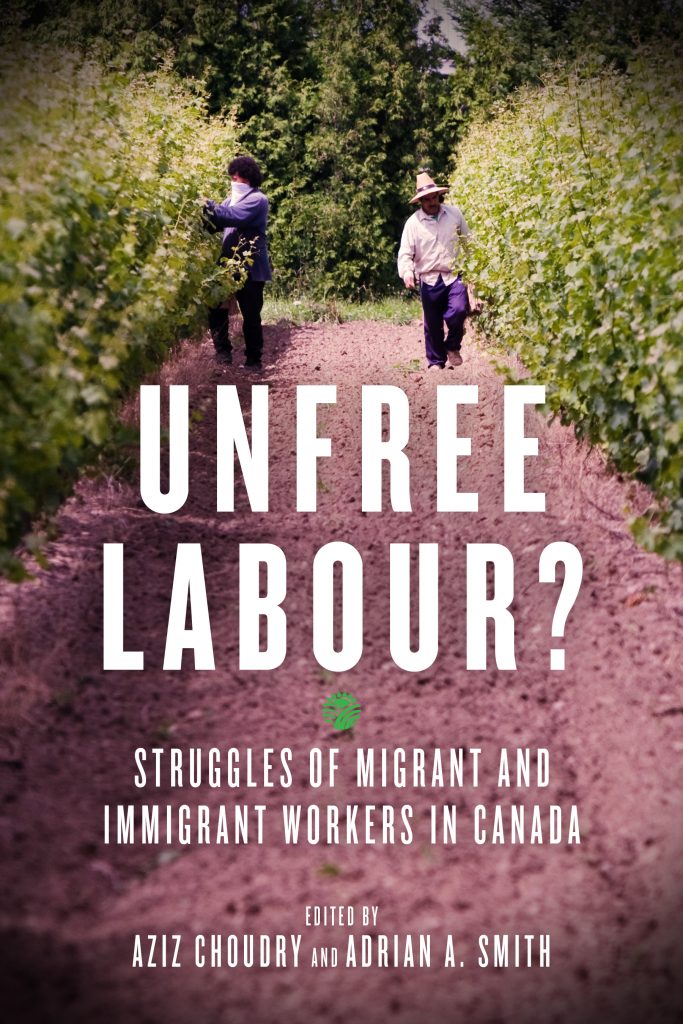

They do the critical work of growing food, serving in restaurants, in the homes of the elderly. They do so over long hours, with few days off, and no vacations. And for all that, permanent residency is being offered to few people every year. Their immigration status is tied to a specific employer so if they are unlucky enough to have a bad boss they can’t simply look for another job. SAWP workers, for one, have to work for a specific amount of time and if they don’t they can be both deported and prevented from being employed by the program in the future. And, while they’re in Canada, their families cannot join them. They’re both isolated from the community and their family, and they have no other source of economic security while they’re here. Migrant workers are, according to the editors of Unfree Labour? Struggles of Migrant and Immigrant Workers in Canada, Aziz Choudry and Adrian A. Smith, “commodities, labour units to be recruited, utilized, and sent away again as employers require.”

And the TFWP is only growing. Before the Harper government put a moratorium on the restaurant industry employing migrant workers (because of inaccurate and divisive fears that migrants were taking the jobs of “real Canadians”) the Stream for Lower-Skilled Occupations grew from having 1,578 workers to 30,267 between 2003 and 2012, with the majority being women.

But while the books various pieces detail the indignities migrant workers experience in their workplaces, and offers a sober look at just how difficult the challenges are in light of the TFWP’s roots in a deep economic incentive and a global structure with an interest in reaping those benefits, they also linger on the victories. They amplify those moments of resistance, courage, and hope, those instances when migrant workers and their allies, with few resources and institutional support, wrested concrete material gains from the government and their employers. And the pieces discuss practical ideas on what to do next, on how to organize differently and creatively to not only win greater concessions but to gain real power.

In October of 2010, migrant workers with the support of Justicia for Migrant Workers began the Pilgrimage to Freedom trek from Leamington, Ontario, the “Tomato Capital”, to the Tower of Freedom “underground Railroad” Monument in Windsor, Ontario. The journey is recurring this year as I write this. In that same province, farmworkers have been excluded from labour relations legislation allowing freedom of association and collective bargaining but, since the 1990s, the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW) has worked to win the legal right to organize and bargain collectively for agricultural workers. The campaign connects legal battles with grassroots organizing so that agricultural workers are already in bargaining units in case a union certification is achieved. In some sites, the UFCW achieved collective agreements obligating employers to help workers apply for permanent residency under the Provincial Nominees Program.

Live-in caregivers have incredible difficulty organizing, since they live in their workplace, but that hasn’t stopped many of them from coordinating with other workers. They “have been overwhelmingly Filipina, giving them a common language and cultural references when they leave their workplaces to seek companionship and services on their days off,” writes Jah-Hon Koo and Jill Hanley in “Migrant Live-in Caregivers: Control, Consensus, and Resistance in the Workplace and the Community.” “Second, in many Canadian cities, the LCP has been the major vehicle for Filipino immigration, removing some of the stigma related to doing domestic work that has been noted in previous studies on domestic work and allowing Filipinas to feel comfortable coming together as domestic workers.” As a result, they’ve been able to engage in direct action casework and have prevented workers from being deported because they were unable to complete the hours required during their work permit period (due to unexpected illnesses or pregnancy). They’ve won mandatory private insurance offered by employers if caregivers are excluded from public health insurance or workers’ compensation; an extension of the time limit for completing the required live-in service; and, now, they are counting hours worked (a required 3,900 hours) rather than simply months, making it easier to meet the requirements during their stay.

Some of the organizing has even gone global. “By organizing protests and worker delegations to address the minister of labour, Barbadian farmworkers demanded an end to double pay, a process whereby workers were paying into both the Barbadian and Canadian unemployment schemes without receiving entitlements in either country,” writes Chris Ramsaroop in “The Case for Unemployment Insurance Benefits for Migrant Agricultural Workers in Canada”.

In 2009, the Toronto Workers’ Action Centre (WAC) worked with the Caregivers’ Action Centre and won new protections for live-in caregivers under the Employment Standards Act. The piece by Deena Ladd and Sonia Singh, “Critical Questions: Building Worker Power and a Vision of Organizing in Ontario” discussed at length the organizing model of WAC. It spoke of their democratic structure, the need to involve workers in campaigns on a deeper level than usual, the lessons of sectoral organizing (although that still poses difficulties for migrant workers who aren’t in the country long enough) and the failure of traditional unions to combat precariousness and the racism of the TFWP.

As informative as the book is, what the reader will likely leave with is the sense that the struggles of migrant workers are fundamental to the labour movement. How employers and friendly governments treat the most vulnerable workers calls on all workers to resist. The book is a vision of what should be – equality for all workers – and gives hints to how we can get there.

“At least in BC,” says Adriana Paz Ramirez, a co-writer of one of the pieces, during the “Organizers in Dialogue” section that closes the book, “we have made a conscious choice to focus on the places where nobody goes – to people’s houses. We start building and opening up spaces where workers can come and relate to each other in a different environment than one of competition. Through that and relationship-building we are working on this transformative aspect of organizing. Although I don’t have a polished definition, I think it has to do with how you regain confidence, regain humanity, regain dignity, regain joy, regain and share this with other people. At least to believe that you are building a sense of community or harmony in the house or farm where you are working and living.”

Back to Aziz Choudry’s Author Page | Back to Adrian A. Smith‘s Author Page