By Andrew Stewart

Washington Babylon

February 1st, 2019

Andrew revisits a classic of underground comix that is a vital artifact of the Sixties…

And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . . So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back. -Dr. Hunter S. Thompson

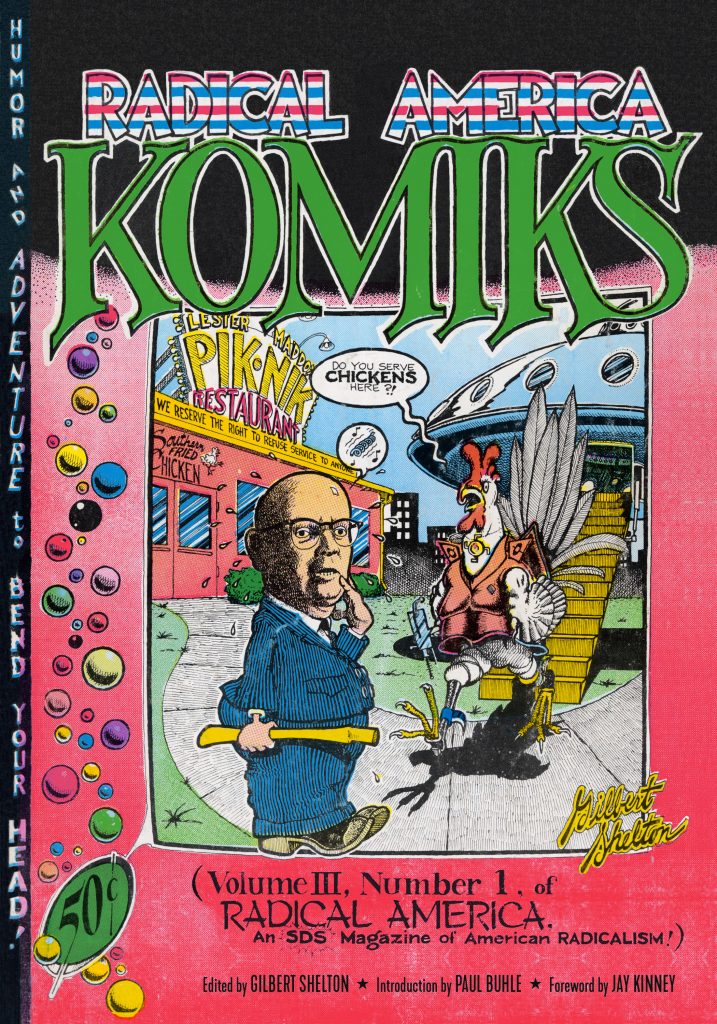

Radical America Komiks was published half a century ago. The fact that many of the contributors to that periodical are still alive is testament to several undeniable factors, including the power of modern medicine, the perseverance of the human spirit, the ineffectiveness of the COINTEL-PRO’s aim to smother all New Left radicals, and the fact that Nixon will have been proven the loser in the final equation.

RAK was, unbeknownst to its contributors, much like Dr. Gonzo’s wave. Within a few years of publication, Students for a Democratic Society (the organization for whom Radical America was a theoretical-cum-academic journal) was imploded by a variety of pressures, not the least of being a locker room scuffle between Maoists, Trotskyists, and various other misbegotten sectarian knuckleheads, including the Weatherman organization.

Someday, perhaps when everyone involved in the struggle is either dead or lost all their marbles in the nursing home, the FOIA requests and de-classifications of the FBI archives and everything else will put together the whole graphic novel and show how much of this inglorious denouement was caused by the COINTEL-PRO effort against SDS. Were the factional splits that ruptured the movement exacerbated by the subterfuge of the FBI? Was it all pre-ordained by J. Edgar Hoover, who by that point had assembled quite the arsenal of operational procedures that dated back to the Palmer raids in 1919-20? When all is revealed, will anyone believe it belongs anywhere besides the comics page?

This extended digression on the immediate aftermath of when the book in question might seem a bit strange. But in fact I see this contextual understanding as vital to a genuine analysis. This is not just a funny book (in both meanings of that word), a monument of comic art. It also is an ink-and-pen time machine to a moment of calm before the storm of the 1970s. From roughly the death of John Kennedy until 1970, the Baby Boomer generation had the world as their oyster. The welfare state existed, full employment was official US government policy, college tuition was basically pennies per semester, and the streets were full of activists who were certain they could change the world, which they in fact did.

Of course, there was just one thing they left out: what was the ultimate goal?

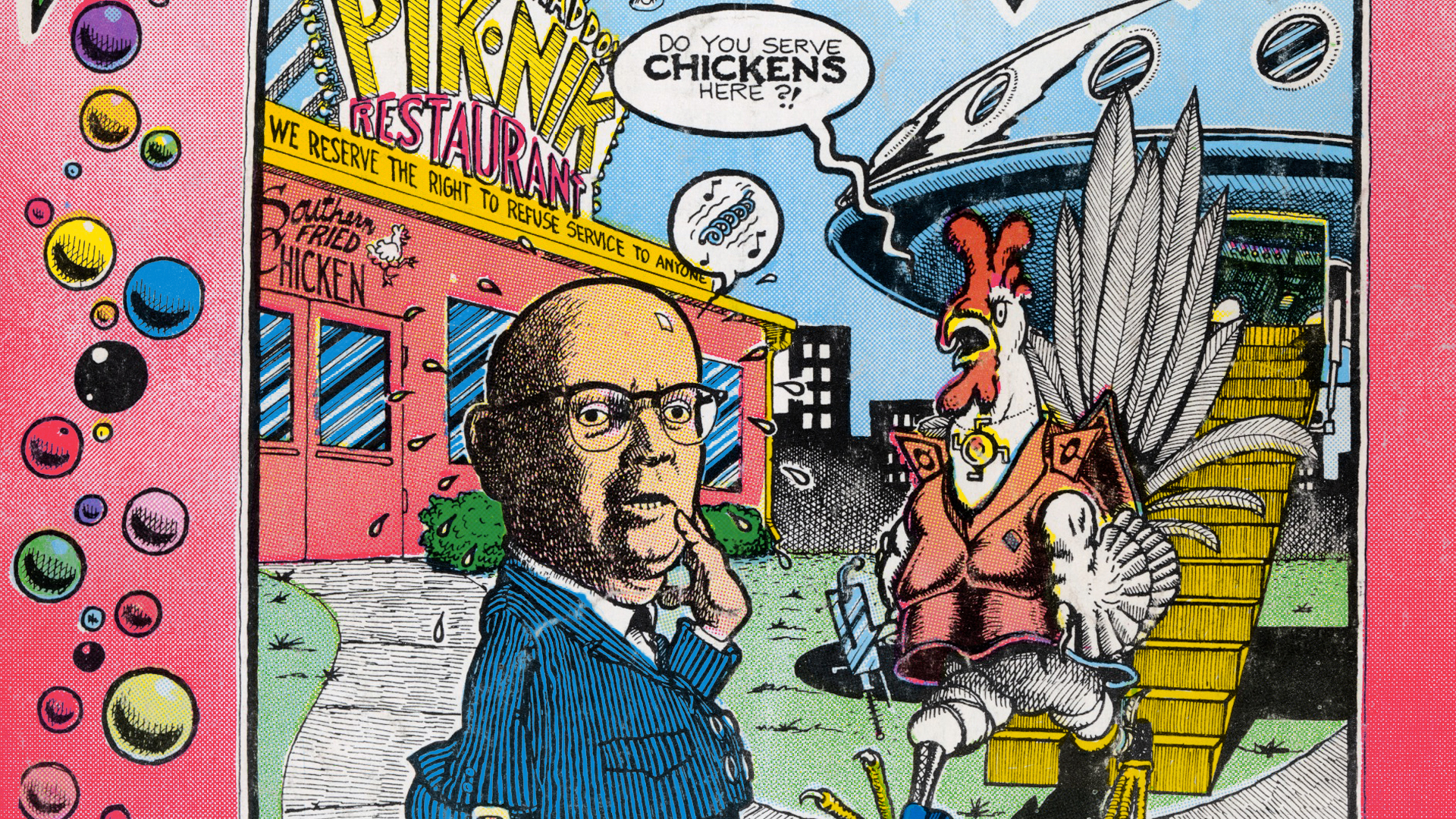

For some, such as Weatherman, the name of the game was revolution. But not everyone actually was grabbing the pitchforks. There is in fact a Mariana Trench separating “I don’t want to go to Vietnam” and “Expropriate the expropriators.”Radical America Komiks was a project developed by the magazine and edited by Gilbert Shelton, who had previously been making his mark in the underground comix circuit in Austin. It straddles this contradiction within the ultimate goal of the movement, and articulates the difference between the two worldviews, reform or revolution, in a hilarious manner.

“We can see better now that RA Komiks connects, not only for me, the EC/MAD COMICS legacy with the future rise of radical graphic novels,” says historian Paul Buhle, who edited Radical America in the late 1960s and has made a second career editing graphic novels. “Gilbert Shelton, the artistic creator of RAK, contributed to MAD founder Harvey Kurtzman’s HELP! magazine in the early 1960s, and the circle around early Underground Comix included some of my future collaborators, especially Spain Rodriguez and Trina Robbins.

Over 42 goofy pages, readers were presented with anarchic, zany strips that pushed all the boundaries of common decency for that period. Included among these was one of the earliest appearances of Shelton’s own Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, the goofball stoners who went on to become a cult classic.

Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers

Also in the mix is Billy Graham being lampooned mercilessly over his well-documented hypocrisy, Jesus Christ being beaten up by cops mistaking our Lord and Savior for a hippie, and Smiling Sgt. Death and His Merciless Mayhem Patrol, a send-up of postwar combat comics like GI Joe that skirts the border between offensive and hilarious in a precarious fashion. This straddling itself is emblematic of the era. The Sixties in America was always jumping between moments of brilliance and incoherence, waging an offensive against The Man and being simply offensive.

Perhaps a bellwether of this dissonance was William Appleman Williams, whose ‘Wisconsin School of Diplomatic History’ provided the pedigree for a multiplicity of thinkers that were published in Radical America. By 1968, after writing his two most popular volumes (and having been red-baited by sycophantic Kennedy court historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. over them), Williams left Wisconsin, infuriated by the New Left’s growing militancy, retreating to the Oregon coast. Almost thirty years after his death, one looks back on his legacy and finds his high estimation for Herbert Hoover, John Quincy Adams, and the Articles of Confederation. He thought that there was something within the United States’ origins that were germinal to a viable decentralized socialism that would shirk the alleged excesses of the Soviet and Chinese revolutions. Those contradictions and paradoxes were emblematic of a movement that undeniably left its mark, a legacy that was most recently on public display with the political contest between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton, both legitimate claimants to the heritage of the Sixties.

That liminality of the legacy of the Sixties is something that historians will grapple with later. For now, perhaps this graphic novel time machine provides the best moral judgment possible until another wave rolls in and helps us all see things from a higher position.