By Mark Hayes

Marx & Philosophy

April 2017

This short text brings together a collection of writings from a relatively obscure member of the Austro-Marxist tradition. Unlike, for example, Otto Bauer or Max Adler, Julius Deutsch appears to have evaded the forensic attention of academic analysis. Gabriel Kuhn has clearly made an effort to rectify this.

Julius Deutsch was born into a Jewish working class family in Eastern Austria in 1884 and went on to become a leading member of the SDAP in a period when Austrian socialists, despite the damaging split caused by the First World War, still retained some aspirations to transform society. Deutsch was a member of Parliament between 1920-33 and was Undersecretary of State in the department of Armed Forces 1918-20. In the context of the emerging struggle against fascism in Europe, he became chairman of the Schutzbund, which was set up to oppose right-wing paramilitary groups like the Heimwehr, and he was a military adviser to the Republican regime during the Spanish civil war. He wrote many books and pamphlets between 1903 and 1960 on a range of subjects including fascism, trade unions, socialism, working class culture and sports (as detailed in the selected bibliography included within this book, 111-14). Publishing a collection of his thoughts on these important themes thus constitutes an interesting and important intellectual and political exercise.

In fact, Deutsch’s work focuses on the cultural dimension of working class resistance and it is important to note that Austro-Marxism, between the wars, was in many respects a cultural endeavour. This was very much based on the SDAP’s control of Vienna, which saw the creation of a large network of innovative communal facilities, including healthcare, education, social services and public transport.

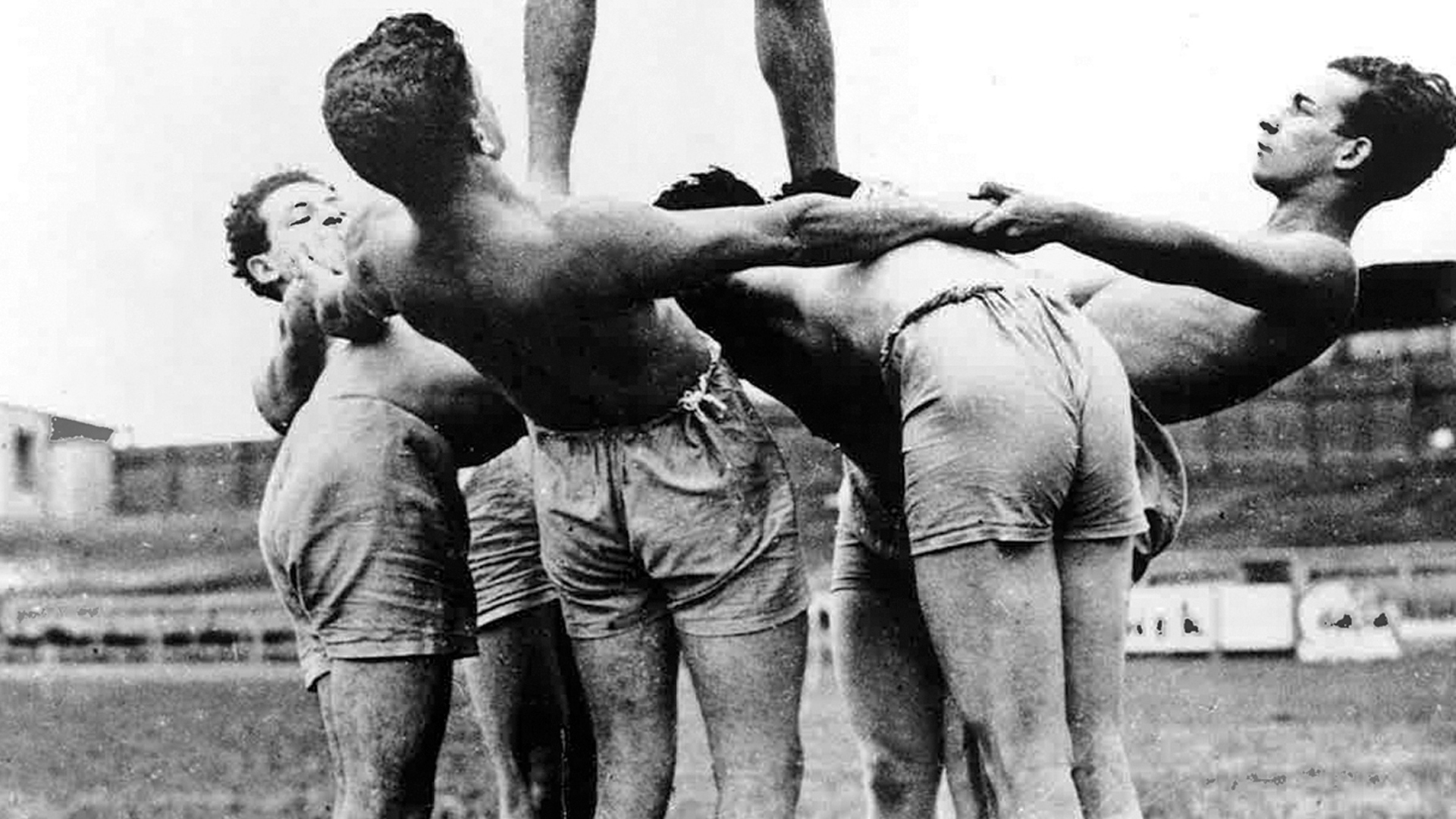

If we look at sport, for example, the German-speaking world was the centre of the workers’ sport movement, which reflected not only a commitment to physical activity, but the organisation strength of the labour movement. In 1894, the Allgemeiner Turnverein was formed as a gymnastics club, which eventually morphed into the Arbeiterbund für Sport und Körperkulture in Österreich ASKÖ (p.26), where the sports practiced included not just gymnastics, but cycling, hiking, swimming, skiing, football, handball, judo and tennis. This organisation became the largest in the world in relation to the population size, with around 300,000 at its peak (26). Despite some early reservations in some socialist circles, the organisation was seen as an auxiliary method of incorporating workers into the wider labour movement. Deutschbecame President of ASKÖ in 1926, and he subsequently assumed the presidency of the Socialist Workers’ Sports International (SWSI), founded in 1920, which at the height of its popularity had around two million members from over 20 nations (27). The values promoted were community, sportsmanship and health, rather than individual competition and commercialism. Such organisations facilitated and expressed a proletarian culture, and reflected a degree of working class agency in the period before the ascendancy of fascism, which would, of course, destroy all such manifestations of worker control.

In Sport und Politik (1928) Deutsch noted the popularity of soccer, which drew large crowds from proletarian areas. Deutsch made the point that, ‘regardless of whether the bourgeois sports clubs and associations try to appear neutral or admit to their political aims, they inevitably practice sports in a way adapted to capitalist thinking and feeling… The brutal and egotistical desire for success that characterises capitalism is reflected in bourgeois sport’ (73). Furthermore:

[I]n sport as in economic life, the success of the individual is everything. A world of sport dominated by the propertied classes is individualistic; it cannot be any other way. In capitalism, success is the only thing that matters. Everyone tries to make it to the top in order to acquire money and fame. All means are acceptable, because once you are at the top, no-one cares about how crooked or straight the path was that got you there (73).

However, Deutsch was not antagonistic toward the achievement of ‘high-end’ performances or the professionalisation of sport, although he rejected the ‘sensationalism’ and ‘low instincts’ which inevitably accompanied it. His vision included the idea that whole communities should become healthier and stronger as a consequence of physical endeavour (74). He explained: ‘we do not want to breed master athletes and chase records. We want to strengthen the people’ (76). Achievements would be pursued collectively, and a necessary corollary of this emphasis on sport was that workers would require more leisure time. Moreover, according to Duetsch: ‘workers’ sport is closely tied to the development of a new proletarian culture’ (77, italics in original). This culture was designed to transcend the narrow nationalism and parochial chauvinism of bourgeois sport. In addition to this, the Naturfreunde (Friends of Nature) founded in Vienna in 1895 became a very successful multi-national hiking association. Healthy strong bodies would help create a new type of person, where the emphasis would be on peace and fraternity: ‘the ultimate goal is to form the future of mankind anew’ (78). So according to Deutsch, the fight against various forms of nationalism, militarism and capitalism would also take place in the realm of sports and physical activity.

Interestingly, the workers’ temperance movement was a related phenomenon. It sought to divert people away from the distractions of alcohol, which was deemed inimical to genuine socialist consciousness. Despite some severe reservations being expressed in other countries, in Austria most of the leaders of the socialist movement supported the struggle for sobriety (36). The Arbeiter-Abstintenbund (Workers Temperance League AAB) was founded in 1905 and Deutsch was a committed member who stressed the need for clarity and discipline in the labour movement, which was inevitably undermined by the influence of excessive alcohol consumption. This strand of Austro-Marxism was clearly committed to re-creating the individual as a class-conscious political activist and it aimed to bring a socialist perspective to the activities of everyday working class life.

The other area where Deutsch made a significant contribution to debate was on anti-fascism, an issue which was of urgent importance at the time. As Deutsch explained: ‘In Austria we have had to repel a wave of fascist attacks over the past two years. We are facing a reactionary onslaught with strong financial backing and ruthless methods’; indeed, Deutsch admitted that ‘it has not been easy to hold out against the storm’, adding prophetically that ‘there cannot be any doubt that a next round will come’ (80). Deutsch therefore reiterated that ‘under these circumstances, the working class has no choice but to prepare its defense’ (83).

In the context of this deadly political struggle key issues were raised by Deutsch, such as the scepticism in some quarters about adopting a militaristic response: ‘The traditional aversion of organised workers to militarism makes the creation and expansion of proletarian defense units difficult. Without the order, discipline and unity of military divisions, useful defense units cannot be built. There is no particular reason why the proletariat should not use military structures’ (59). According to Deutsch, the problem with the military model was primarily that it was associated with the army, which was part of the machinery of state oppression, and hence hostile to the people. However, Deutsch argued that ‘proletarian defense units are entirely different. They belong to the people’s flesh and blood’ (p.59-60). Therefore, for Deutsch, using a military structure (platoons, companies and battalions) and even techniques (such as uniforms, flags and parades) was not ‘militarism’ as such, because the purpose was entirely different. In fact, Deutsch even suggested that ‘the clever use of people’s emotions must not be left to reactionaries’ (61) because it can convey power and momentum, and send a message to the enemy. Deutsch was evidently acutely aware of the fascist threat, and advocated the deployment of a variety of methods in order to defeat it. Deutsch even made an effort to unite all of Europe’s anti-fascist militias into a single organisation at a conference in Vienna in 1926: the InternationaleKommission zur Abwehr des Faschismus (International Commission for the Defence Against Fascism).

Of course, political tensions between the SDAP and right-wing reactionaries, including pan-German Nazis, led to civil war in Austria in 1934. Although the fascists emerged victorious, presaging the Anschluss in 1938, the resistance led by the left raised interesting questions about the nature and purpose of anti-fascism. The aim of the Schutzbund was obviously to resist the fascists but, despite the radical rhetoric, in many ways the organisation concentrated its efforts on negotiated de-escalation rather than outright confrontation. This was clearly a fatal error and allowed fascists the public space in which to grow. The struggle of those elements in the Austrian working class who actually decided to fight was unquestionably noble, but the SDAP had failed to sufficiently mobilise the masses against the threat. The Austrian Parliament was suspended in March 1933, and by the time the SDAP newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung was prohibited in January 1934, the critical moment had passed, and the uprising in February was destined to be yet another heroic failure. All workers’ organisations in Austria were subsequently dissolved as dictatorial rule was reinforced.

In effect, the struggle to prevent the political ascendancy of fascism was a failure in Austria, and in large part this was a consequence of the failings of an anti-fascist leadership intent on preserving a balance between reformism and revolution. A preoccupation with the assumptions of the former not only fatally undermined the latter, but led directly to the political success of their ideology’s bitterest enemy. However, as Kuhn points out in his useful introduction, ‘the positive consequences of the Schutzbund must not be overlooked amidst the frustration over missed opportunities and eventual defeat. The Republican Schutzbund was the first European effort to meet the fascist threat with an armed organisation designed specifically for that purpose’ (42). Indeed, the aspirations which were reflected in the activities of inter-war anti-fascist organisations remain of profound significance now, in an era when the electoral success of authoritarian populism threatens to unleash another wave of fascist barbarism. Even Deutsch’s observations about the role of sport have a contemporary relevance in a society which is currently dominated by individualism, commercialism and the apparently unending quest for profits.

In conclusion, the documents supplied in this short text are of deep political and ideological significance. The sad journey undertaken by Austro-Marxism – from revolutionary praxis to compliant political parliamentarianism of the post-war Sozialdemokratische Partei – is a familiar one, and its appraisal is clearly beyond the scope of this book. However, if that depressing process can be set aside, and Deutsch’s work examined for intrinsic merit, there is much to discuss, and even admire. Gabriel Kuhn and PM Press have performed a valuable task in shedding light on the literary contribution of a man whose life’s work involved advancing the interests of those who were oppressed by an exploitative economic system. The issues raised here are not simply of interest to the archivist or historian because Deutsch’s observations have a much more immediate, contemporary resonance.